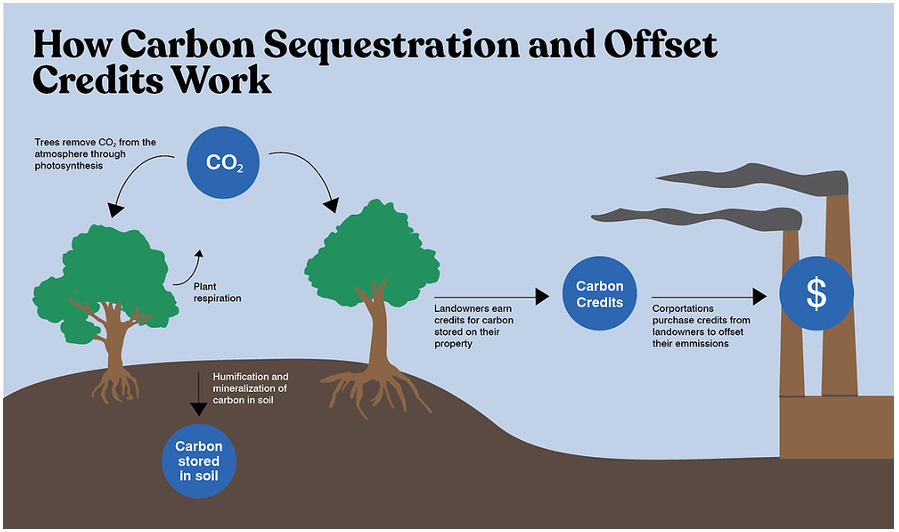

The concept of “carbon farming”—or paying farmers to store carbon in the soil—has become a popular topic as business leaders, politicians, environmentalists, and individual citizens look for ways to slow down climate change.

The idea is relatively simple. Companies that cannot or choose not to reduce carbon emissions instead pay a farmer to store carbon in the soil, with the goal that more carbon is getting stored than is being emitted. Certain farming practices, such as no-till and using cover crops, naturally sequester or pull carbon from the air and store it in the soil. Over time, carbon dioxide is reduced in the atmosphere while organic matter is increased in the soil. Farmers receive payments for storing carbon while also reaping the benefits of improved soil health.

However, the devil is in the details. How do we know how much carbon is getting stored? How much is it worth? Who is verifying practices and managing payments? Well, carbon markets are new and evolving, participation is voluntary and limited, and standards for verification are still being developed. Some might say it is the Wild West when it comes to carbon markets.

A myriad of options exists, but each company has its own requirements. Some want to reward recent/past practice adoption, while others expect practice adoption while actively under contract. Most require extensive recordkeeping and reporting to assist in the measurement of carbon sequestration. At least one company allows the farmer to set the price of their carbon, while most have a uniform price structure based on the practice(s) implemented. Some programs limit payments to cover crop and no-till adoption, while others are expanding to a variety of other practices with more or less scientific rigor behind their sequestration abilities.

Purdue’s Carson Reeling and Nathanael Thompson have been keeping up with the trends in carbon markets. In a recent article titled “Opportunities And Challenges Associated With “Carbon Farming” For U.S. Row-Crop Producers” they note the sheer amount of payment offered is often not enough to cover the initial cost of realizing practice adoption and changing farm management accordingly. However, significant potential exists for farmers who want to gain soil organic matter to use the markets as a way to lessen the blow of any learning experiences acquired on the way toward conservation cropping systems.

In addition to commercial row crop production, livestock sectors are looking at ways to adopt carbon neutral practices. In one example, the dairy industry is looking to achieve greenhouse gas neutrality by 2050 (https://www.usdairy.com/sustainability/environmental-sustainability). However, the private carbon markets have not at this point found a good incentive structure for most livestock production practices. At this point in time, livestock producers miss out on the markets.

There is still much to learn concerning carbon markets and how producers can get involved. The option may not fully offset greenhouse gas emissions, but will certainly help account for a piece of the puzzle. For more information, visit the USDA Carbon website.

The figure illustrates how carbon offset credits work. Source: Jonathan Zhou’s article titled “A deep delve into Biden’s environmental policies”.

Farming for a Better Climate is written in collaboration by the Purdue Extension, the Indiana State Climate Office, and the Purdue Climate Change Research Center. If you have questions about this series, please contact in-sco@purdue.edu.