Cover crops are nothing new, but their relationship to a changing climate might be new to many farmers. Keeping the soil covered with plants and filled with living roots builds soil carbon, keeping heat-trapping carbon dioxide out of the air.

Compared to many of our neighboring states, cover crops have been heavily adopted in Indiana. According to 2021 Natural Resource Conservation Service data, 1.59 million acres of cover were planted across the state last year (including the winter wheat cash crop). St. Joseph County led the way in the state, with over half of their acres surveyed planted to some kind of cover.

Many cover crops are planted in an attempt to control soil erosion, promote soil health, or combat pests and weeds. However, the ability of cover crops to help soils store carbon is an important component of their management as well. Bare soils still have organic matter in which microorganisms are actively working, feeding, and growing. Those microorganisms break down carbon (and nitrogen) which are released into the air as greenhouse gasses. The resultant organic matter percentage in that bare soil declines. When fields are kept with growing plants year-round, and decaying plant matter is kept on the field, microbes release fewer greenhouse gases into the air, and organic matter in the soil increases.

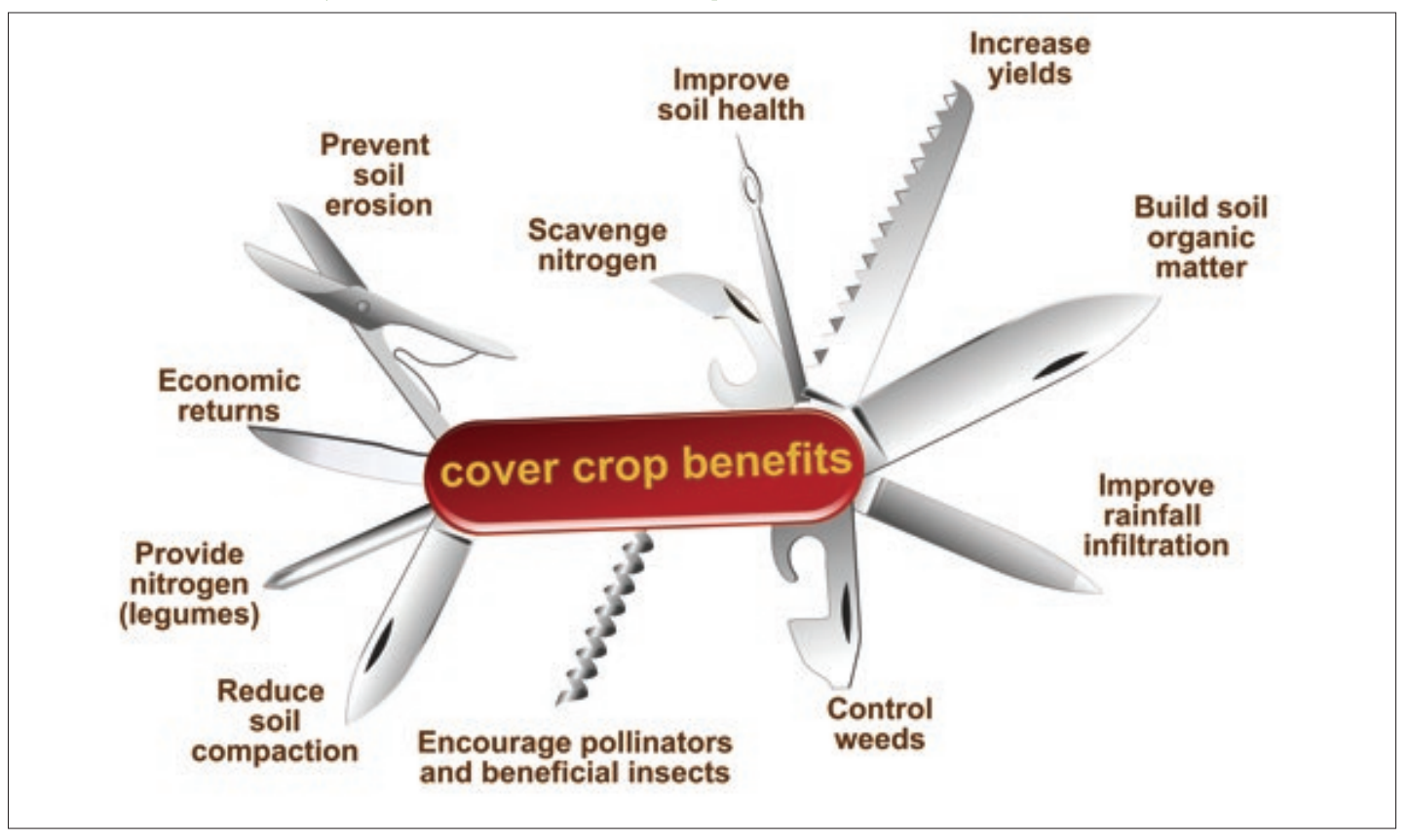

This graphic shows the many benefits that cover crops provide over time, which include the ability to better cope with weather extremes (such as improving rainfall infiltration) and slowing climate change (such as building soil organic matter). This graphic originally appeared in Cover Crop Economics, a SARE bulletin published in 2019, and was illustrated by Carlyn Iverson.

Farming a Better Climate is written in collaboration by the Purdue Extension, the Indiana State Climate Office, and the Purdue Climate Change Research Center. If you have questions about this series, please contact in-sco@purdue.edu.