Agriculture is part of the solution when it comes to combating climate change, and it all starts with soils. Why? Out of all agricultural practices, soil management is the main contributor of greenhouse gas emissions (68%), such as carbon dioxide (CO2) and nitrous oxide (N2O). Your approach to soil management will have a significant effect on the amount of carbon that is either stored in the ground or released to the atmosphere.

For years the most prevalent soil management practices involved conventional tillage, which has provided benefits in fighting weed pressure and increasing seedbed preparation. However, those years of soil management relying on conventional tillage have also contributed to soil organic carbon (SOC) loss, as this practice disturbs soil aggregates, exposes soil organic matter to degradation, and enhances CO2 emissions. In search of soil health benefits, many agricultural producers are now looking at other options to manage soils through conservation tillage.

As a concept, conservation tillage has been around a while and involves any tillage practice that leaves 30 percent or more of crop residue on the soil’s surface. No-till, strip-till, and ridge-till are just a few examples. Many agricultural producers have incorporated these methods as an effective way to protect soil against water and wind erosion. Other benefits of conservation tillage include, enhanced water quality and water conservation, less fuel consumption, lower labor costs, and improved soil structure. According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service, just over one-quarter of all U.S. cropland acres are in no-till and another quarter report using other conservation tillage practices. The highest adoption rates are found across the Corn Belt.

It’s the soil structure improvements that make conservation tillage a powerful tool in the fight against climate change. Improving soil structure reduces CO2 emissions by slowing microbial decomposition of SOC. This means more carbon is locked into the soil and kept out of the atmosphere where it would otherwise contribute to warming temperatures. Recent research suggests that no-till farming has the potential to sequester from 0 to 0.4 metric tons (MT) per acre per year, depending on climate and soil type. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, converting all U.S. cropland acres into no-till would store 123 million MT of carbon per year, equivalent to about 2% of all U.S. CO2 emissions in 2019.

Converting to a conservation tillage system may seem like a no-brainer, but there are drawbacks such as increased chemical costs for pest management and susceptibility to cool and wet soils in the spring. Some producers are apprehensive due to the steep learning curves that exist with implementing conservation practices, the social stigma when fields don’t appear ‘clean’, and the often-required redesign of their conventional management practices. Another concern producers face is the fear they won’t compete with yields from a conventional system, thus reducing their farm’s profitability.

However, under certain weather and climate patterns, conservation tillage can actually help protect yields. A recent Purdue University study compared tillage practices on mollisol soils and their profitability under current and future weather and climate patterns. The research shows there is already an economic incentive for agricultural operations to adopt some form of conservation tillage, and the economics are enhanced in a changed climate.

So, should you continue conventional tillage practices or should you migrate to a conservation tillage system? The answer is probably different for each of you. If you are considering adopting a conservation tillage system there are many valuable resources available through Purdue University Extension, the United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, Soil and Water Conservation Districts, your peers, and consultants.

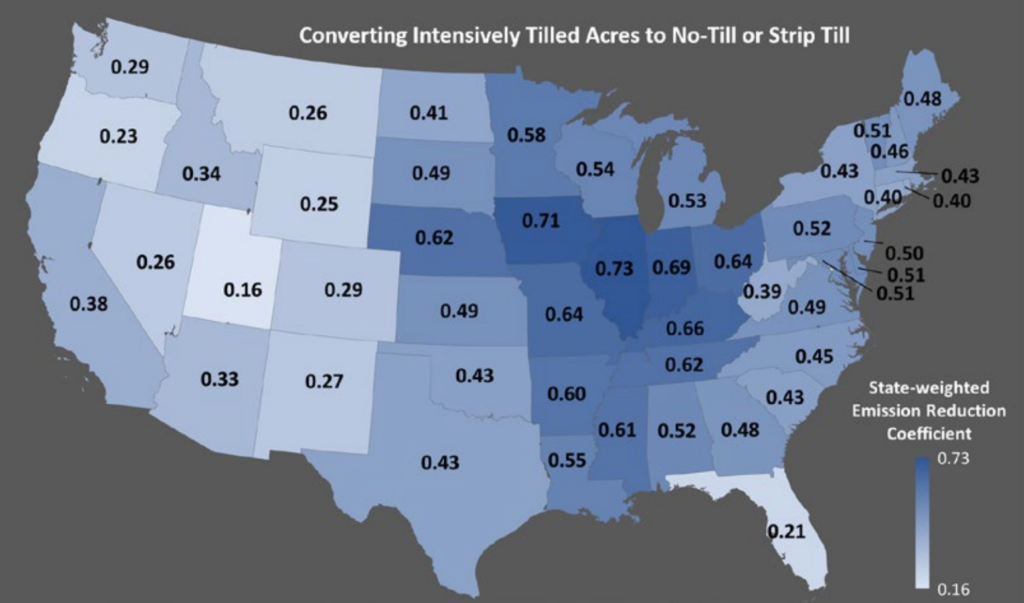

Graphic originally appeared in the report Combatting Climate Change on US Cropland published by the American Farmland Trust (2/5/2021).

Adopting strip-till or no-till practices can help keep carbon in the ground. This graph shows estimates of how much these practices can reduce heat-trapping gas emissions, by state. Numbers shown are the average amount of heat-trapping gas emissions saved, as tons of CO2 equivalent per acre per year, averaged across each state’s cropland.

Farming a Better Climate is written in collaboration by the Purdue Extension, the Indiana State Climate Office, and the Purdue Climate Change Research Center. If you have questions about this series, please contact in-sco@purdue.edu.