When it comes to retaining water in the middle of a summer dry spell or absorbing extra rainfall during a spring storm, our soils need organic matter to keep roots happy and nutrients cycling. The amount of organic matter in our soils can vary greatly based on the soil type, previous vegetation, current vegetation, and farm management practices. Soil organic matter (SOM) also plays a role in preventing excessive impacts of climate change, because it contains most or all of the soil’s carbon – carbon that would otherwise be in the atmosphere trapping heat. So when we talk about farming for a better climate, managing the carbon in our soils is a big part of the discussion.

Soils are comprised of four components: water, air, mineral particles, and organic matter. The sizes of mineral particles define the soil type as sand, silt, clay, or a combination (defined as a loam). Water that penetrates into soil can be reached by plant roots, and air between the particles allows for root growth and aerobic bacterial life. Organic matter, meanwhile, fits into the equation as being a nutrient source, among other things. The word “organic” derives from the chemistry definition, that being containing carbon atoms or derived from carbon compounds. Those carbon-containing compounds in organic matter are various types of dead and decayed plant or animal material, including animal manures. The usual organic matter content of our soils can be anywhere from less than 1 per cent to over 10 per cent in the muck soils of Northwestern Indiana.

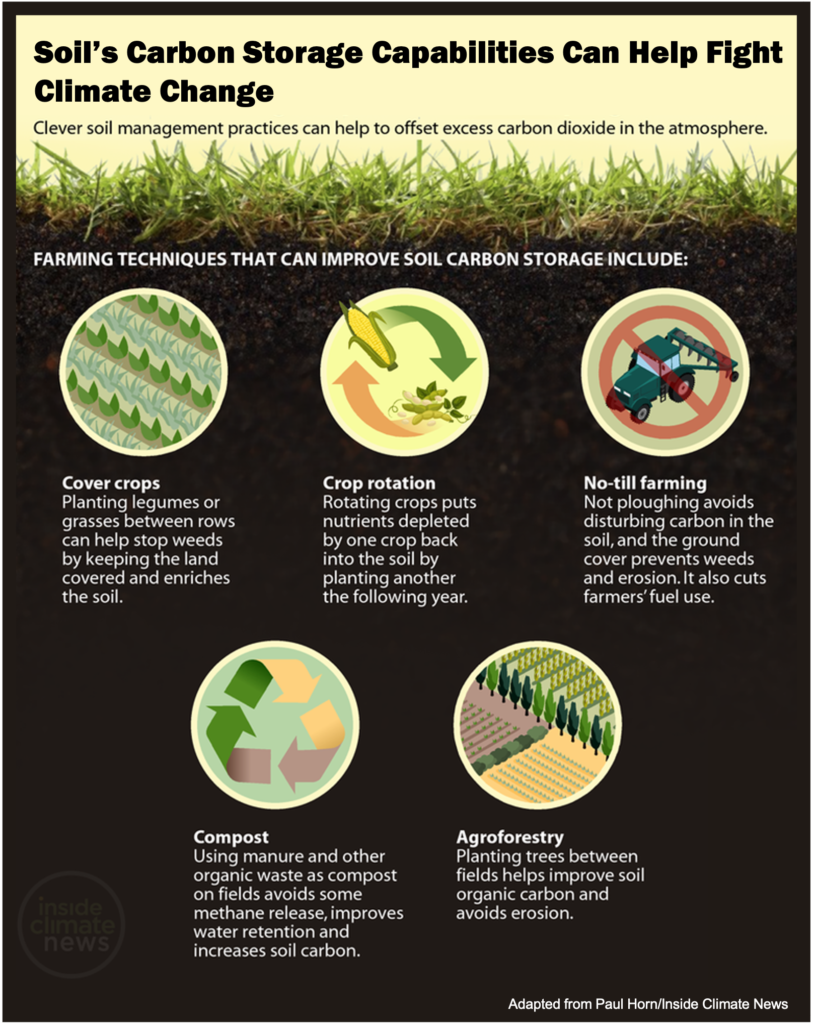

Plants use energy from the sun to scrub CO2 out of the atmosphere and return the carbon to our soils, boosting SOM. The emerging carbon markets are rewarding farmers for practices that reduce CO2 emissions and increase carbon storage in the soil through cover crops, perennial cropping systems, reduced tillage systems, and other practices that increase organic matter in the soil. This can be complicated, though, because soils vary in their ability to store organic matter over time. According to research conducted in the Corn Systems Coordinated Agricultural Project, no-till management systems can return a detectable difference in 11 to 71 years, depending on conditions. For this reason, single practice adoption, while beneficial, is often not enough to yield immediate benefits.

As farmers are working to build SOM by adopting conservation practices, unfortunately, climate change itself is making this a more challenging task. Long-term weather observations show that local temperatures are warming. Warmer temperatures increase the speeds at which fungi and bacteria break down SOM. Soil erosion associated with heavier rainfall events will wash more organic matter into streams and rivers. Again, weather observations show heavy rainfall events are larger and more frequent today compared to 50 years ago. Very little organic matter exists in subsoil, so protecting topsoil is the first step towards building SOM. Keeping a green cover crop is another excellent method to build SOM, and something we’ll explore in future articles.

Ultimately, economic benefits come from having adequate SOM. SOM greater than 3 per cent may prevent the need for supplemental crop sulfur due to adequate amounts cycling in soils. Some farms claim to be able to completely eliminate synthetic fertilizer applications by focusing on organic matter management. With fertilizer being the greatest on-farm variable cost, as well as a significant contributor to climate change, reductions in that column make a big difference on the farm’s bottom line.

Graphic originally appeared in Why Farmers Are Ideally Positioned to Fight Climate Change published by Inside Climate News (8/24/2018).

From planting cover crops to no-till farming to agroforestry, there are many practices that farmers can use to increase the amount of carbon stored in the soil.

Farming a Better Climate is written in collaboration by the Purdue Extension, the Indiana State Climate Office, and the Purdue Climate Change Research Center. If you have questions about this series, please contact in-sco@purdue.edu.