Invasive Species

Management of Spotted Lanternfly

Robert Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator, Extension Entomology, Purdue University

If you want to view as pdf, click here

The spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula, (SLF) an invasive planthopper from Asia, has been the subject of a lot of media attention in the last few years. This exotic pest can do considerable damage to several native tree species such as walnut and maple, as well as agricultural commodities such as grapes. It was first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014, though researchers believe that its initial invasion started two years prior after being accidentally shipped on imported stone. In Indiana, SLF was detected in 2021, infesting Switzerland and Huntington counties After spreading through the northernmost counties of the state, SLF has been detected as far as Bartholomew County. The Indiana Department of Natural Resources and Purdue University have been working together to mitigate the spread of SLF as well as educate Hoosiers on what they can do to help. Indiana residents can help safeguard their homes, businesses, and natural areas by keeping up-to-date on its spread.

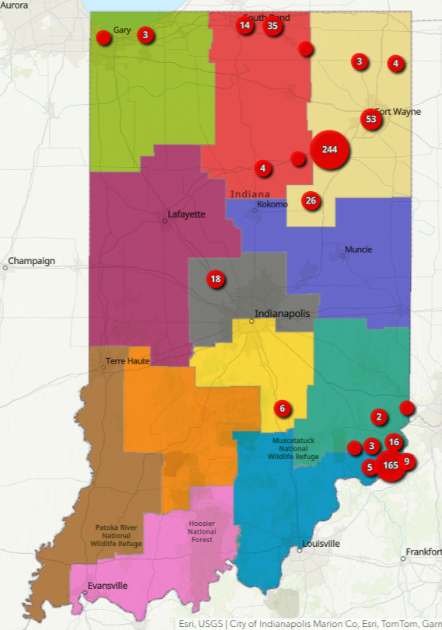

Indiana DNR maintains a map of infestations on their website (https://www.in.gov/dnr/entomology/pests-of-concern/spotted-lanternfly/)

LIFE CYCLE

Eggs

Spotted lanternflies lay eggs in masses of between 30 to 60 eggs, typically arranged in neat rows. The eggs are covered in a protective substance that closely resembles mud, making detection of egg masses challenging. Initially, this substance will appear whitish, eventually turning pink and dark tan as it dries. It is not unusual to find egg masses that are only partially covered, or even masses that completely lack any protection. Spotted lanternflies often lay eggs on or near their preferred host plants, but they will utilize a variety of substrates. These surfaces include tree bark, rocks, the siding of a house, or the outside of a train car, to name a few. Adults will begin to lay eggs starting in September until the first freezing temperatures. Egg masses will persist through Indiana’s winter season, eventually hatching in the spring.

Egg masses laid on tree (Photo credit: Vince Burkle, IDNR)

Nymphs

Spotted lanternfly develops through incomplete metamorphosis; immature stages, called nymphs, resemble smaller, wingless versions of the adults, as opposed to the caterpillars and grubs seen with other types of insects. Nymphs will begin to appear in April or May, developing through four developmental instars. With each instar, the nymph will grow larger, develop wingpads, eventually changing color and more closely resembling their adult size and shape. Early instar nymphs are black with a white dot pattern, while later instar nymphs will be bright red with black and white patterning. When they reach this stage, nymphs are easily confused for a number of insect look-a-likes, such as milkweed bugs or lady beetles. It should also be noted that nymphs have a protrusion from their head that make them easy to confuse for insects such as weevils, but this protrusion is lost once they become adults. Spotted lanternfly nymphs are very mobile and will move between host plants, typically feeding from twigs and smaller branches. They will continue to feed until they molt into their adult form in July or August.

4th instar nymphs (Photo credit: Vince Burkle, IDNR)

Adult

Adult spotted lanternflies are winged insects that share many traits with their distant cousins: cicadas, leafhoppers, and aphids. Their body is approximately one inch in length and a half inch in width, with wings that form a roof-like shape that covers their abdomen. The forewings are beige with a pattern of black dots, with a patch of darker grey at the ends of the wings. The hindwings are a striking bright red and black pattern with white stripes. The abdomen is bright yellow with black stripes, though that may only be seen when wings are spread or if the abdomen is distended. Spotted lanternflies have piercing/sucking mouthparts, also known as a rostrum. These mouthparts are used like a syringe, capable of piercing tough plant tissue and extracting the sugary, nutrient-rich sap. Since these insects can’t process the amount of sugar consumed, they excrete it in the form of sticky waste known as honeydew.

Adults are poor fliers and will travel to different hosts and egg-laying substrates through a combination of flight, walking, and hopping. They often gather in large numbers and initially start to feed on preferred host plants. As host-plants become overwhelmed, they will move to other hosts such as black walnut and maple. Females will lay one or two egg masses during their lifetimes. Spotted lanternflies have only one generation per year, with adults dying with the first freeze. In Indiana, active adults have been seen as late as November.

Spotted lanternfly adults on Virginia creeper (Photo credit: Vince Burkle, IDNR)

IMPACT

When it comes to understanding the damage done by spotted lanternfly, there are a few important factors to consider. Firstly, spotted lanternfly prefers to hit the same ‘hot trees’ year after year. Once the insects find a plant that offers a good source of nutrition, subsequent generations will continue to take advantage of that resource. This tends to result in large groups of lanternflies gathering on the same plants each year. Secondly, feeding by spotted lanternfly results in thousands of tiny wounds in a tree. While many trees will be resilient to feeding activity, repeated wounding can allow entry by a number of pathogens. Repeated infestations year after year will result in reduced plant vigor and a compromised ability to overwinter. Lastly, as mentioned previously, this insect produces honeydew, much like aphids. The amount of honeydew produced is substantial, and covers understory plants with sticky, sugary secretions. This creates an excellent substrate for the growth of sooty mold, inhibiting the ability of the plant to photosynthesize.

HOST PLANTS

There are over 100 different plant species that spotted lanternfly can use as hosts in the state of Indiana. Although these plants may experience harm due to insect feeding, they typically recover and persist following an infestation. A subset of these plants, however, can be severely damaged or killed with repeated, heavy infestations.

Immature spotted lanternfly on tree-of-heaven (Photo credit: Eric Biddinger)

The most preferred host-plant of spotted lanternfly is the invasive tree-of-heaven, Ailanthus altissima. In their home range, tree-of-heaven acts as the primary host of spotted lanternfly, and the insect is rarely found on other plants. Tree-of-heaven is a notoriously difficult species to manage outside of its native range and is considered a major problem in most areas where it’s found. It can grow upwards of 80 feet tall and more than 3 feet in diameter, and like many invasives, will outgrow and outcompete native plants for space. Learn more about this plant by checking out the Purdue Extension publication FNR-633-W, “Tree of Heaven, Ailanthus altissima”. Spotted lanternfly is found in tree-of-heaven year-round, and they will also use it as their primary choice for oviposition. Most, if not all, infestations found in the state of Indiana are associated with unmitigated stands of tree-of-heaven being present. There is no evidence that spotted lanternfly infestations will control tree-of-heaven.

Vineyards are at most risk of severe damage from spotted lanternfly. Feeding on grapevines often results in significant damage and usually leads to the death of the plant. Feeding activity can reduce key plant nutrients such as carbohydrates and nitrogen, significantly reducing yields, and increasing plant mortality (see Spotted Lanternfly Management in Vineyards, Penn State Extension). Adult spotted lanternflies begin moving onto grapes in August, and the highest populations occur in September. Grapevines are also a viable egg-laying substrate for spotted lanternflies.

In addition to tree-of-heaven and grapes, spotted lanternfly will infest black walnut, American river birch, most maples species in Indiana, willow, sumac, and roses, including multiflora rose. While the damage done to these trees is less severe than grapes, repeated infestations will diminish the overall health of the tree. After a few years of feeding, trees lose their ability to survive the winter season, and become more susceptible to pathogens.

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

Spotted lanternfly was first detected in Indiana in 2021 and has since spread to 15 different counties throughout the state. Infestations were first found in Huntington and Switzerland counties in stands of tree-of-heaven in both residential and rural locations. While both infestations were strongly associated with the insect’s primary host, Indiana DNR has identified instances where infestations are moving to other nearby plants. Purdue researchers have begun to observe that, over the course of the summer, spotted lanternfly will move to other host plants, particularly black walnut. Since 2021, the insect moved a significant distance and has been detected in several more counties, including Elkhart, Allen, Grant, Boone, Miami, Noble, Dekalb, Bartholomew, Porter, St. Joseph, Wabash, and Ohio counties. You can see current locations and report sightings by visiting the reporting website hosted by Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources using the link at the end of this guide.

WHAT CAN I DO?

Cultural Control

Spotted lanternfly populations develop quickly, so it’s important to understand how best to manage this insect and its habitat. Integrated pest management strategies will yield the best results over time and reduce the chances of infestations returning. By focusing on the right management practices based on host-plant and the life stage of the insect, the efficacy of your treatment plan greatly increases.

To protect your property, to the first step is to scout and eliminate infestations of tree-of-heaven. As mentioned above, tree-of-heaven is the primary host of spotted lanternfly in their native environment. If this tree is present, spotted lanternfly will use it for food and as an egg-laying substrate. By treating and removing infestations of tree-of-heaven, you’ll not only reduce the likelihood of spotted lanternfly invasion, but also remove an aggressive exotic plant that damages buildings and alters landscapes.

Spotted lanternfly can be mechanically removed by hand. Outreach campaigns have advised residents to “stomp” or “squish” spotted lanternfly as soon as they find them. While this is still recommended, the number of lanternflies will outpace a person’s desire, and ability, to kill them. Egg masses can be scraped up to egg hatch which is roughly mid-April in the south and late April to early May in the north. However, many of the egg masses may be high in trees and other areas that are difficult to access. Using a tool like a scraper or plastic card, the masses can be scraped off and deposited into an alcohol solution or a bucket of soapy water. When scraping, the tool should be pressed down onto the mass until the eggs are crushed.

Biocontrol

There are few options when it comes to a biocontrol plan to manage spotted lanternfly. Natural enemies will prey on the insects, but not to any degree that offers effective population reduction. Two native entomopathogenic fungi, Baktoa major and Beauvaria bassiana, will infect spotted lanternfly, and it’s even possible to find examples of this in the wild. One of the fungi, B. bassiana, is already formulated to treat insects as a biopesticide, however, its activity on spotted lanternfly is inconsistent and requires further research before recommending its use. There are parasitoids from spotted lanternfly’s native range that are being studied for use as biocontrol agents, however, they are very difficult to rear outside that range, and research is ongoing to determine their efficacy and suitability in unfamiliar environments.

Potential fungal infection on adult spotted lanternfly (Photo credit: Vince Burkle)

Trapping

Spotted lanternfly can be successfully trapped as a nontoxic, low-impact management strategy. There are two recommended methods of trapping this insect: sticky bands and circle traps. Sticky bands are bands of cloth, plastic, or similar materials that are covered in a substance that, as the name indicates, is very sticky and prevents the insects from getting free. The bands are wrapped around the trunk of a tree, taking advantage of the insect’s tendency to move across the trunk in search of feeding sites. However, traps that use sticky substances are not discriminating in what organisms are captured, including birds, mice, and more. The risk of non-target capture can be mitigated by rigging a raised guard to prevent larger animals from getting caught. Circle traps, on the other hand, do not use any harmful substances to aid in trapping. These traps are designed to funnel an insect into a dead-end container that prevents them from escaping. Circle traps can be purchased from home supply stores or even crafted at home. Check out the resources at the end of this publication for more information on building circle traps.

Chemical Control

Chemical treatment of spotted lanternfly is an effective management strategy. There are several insecticide options depending on the time of year and age of the insects. During the overwintering egg stage, the insects are well-protected by the mud-like secretion covering the egg masses. However, horticultural oils can be effective at reducing the number of viable eggs, particularly soybean oil; any application of these products should be handled with care due to the risk of phytotoxicity. Research has indicated that the efficacy of dormant and horticultural oils can be variable, but mortality rates of up to 75% are possible (Spotted Lanternfly Management Guide, Penn State Extension).

Contact insecticides are applied directly to spotted lanternflies or onto the plant where the insects will encounter the insecticide. These products may have broad-spectrum activity, and so it is important to follow label guidelines to reduce impact on beneficial species. Residual effects typically last for a few days. Systemic insecticides are one of the most effective chemical treatments of spotted lanternflies. Systemic insecticides are absorbed into plant tissues, killing herbivores that consume those tissues. These types of pesticides can be formulated as a soil drench, used as a soil or tree injection, or even as a seed coating in many agricultural crops. Systemic insecticides also have a much longer residual effect, measured in weeks or sometimes months. This period of time will vary by product and by the time of year the application is made. Since the toxicity persists in plant tissues, it is important to do applications post-bloom to avoid impacting pollinator populations. so many individuals trying to manage an infestation at home or in the garden may find contact insecticides a more viable option. A selection of pesticides has been shown to have significant impact on spotted lanternfly infestations. In terms of contact insecticides, products containing bifenthrin and carbaryl appear to have the strongest impact, though carbaryl’s residual activity is generally poor. Examples of these products can be found under a variety of brand names, and many are available ready-to-use. Treatment with contact insecticides can generally be done for spotted lanternfly May through October, targeting both nymphs and adults. Among systemics, dinotefuran appears to have the greatest effect, followed by imidacloprid. Treatment with systemics can be done July through October, however, Indiana DNR recommends applications should be conducted between mid-June to the end of July for greatest impact. Many systemic insecticides are restricted-use and may have additional requirements before use in your area, so please consult your local cooperative extension office or a professional service before using these products.

|

Active ingredient |

Application method |

Timing |

|---|---|---|

|

Bifenthrin |

Contact/Spray |

May - October |

|

Carbaryl |

Contact/Spray |

May - October |

|

Horticultural Oil |

Contact/Spray |

February - April |

|

Insecticidal Soaps |

Contact/Spray |

April - June |

|

Dinotefuran |

Drench, Trunk spray or injection |

July - October |

|

Imidacloprid |

Drench or injection |

July - October |

|

Selection of example pesticides for use on spotted lanternfly. This list is not comprehensive and research is ongoing to determine additional options. Always fully read the label of any insecticide before use. Dinotefuran and imidacloprid should be applied either before or after bloom, never during. |

||

When applying pesticides, always follow label directions. The label is the law, and the instructions not only keep you and your environment safe but also increase the efficacy of the application itself. The label will also include instructions and information that inform the user on the toxicity of the product, how to avoid non-target damage or drift, and how to safely store the product once the application is done.

We are still learning about the spotted lanternfly’s distribution through Indiana, and we need the help of citizen scientists to effectively track the insect’s movement. Please report any detections of spotted lanternfly using the resources listed below. You can also feel free to reach out to Bob Bruner, Exotic Forest Pest Educator, by emailing rfbruner@purdue.edu, or you can report sightings by calling 1-866-NOEXOTIC. Special thanks to Dr. Alicia Kelley and Eric Bitner for their expertise in reviewing this publication.

Resources

- Penn State Extension Spotted Lanternfly Website

- “How to Build a Spotted Lanternfly Circle Trap” Penn State Extension

- Indiana Department of Natural Resources Reporting Tool

- Early Detection and Distribution Mapping Systems

- Great Lakes Early Detection Network

December 2025

It is the policy of the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service that all persons have equal opportunity and access to its educational programs, services, activities, and facilities without regard to race, religion, color, sex, age, national origin or ancestry, marital status, parental status, sexual orientation, disability or status as a veteran. Purdue University is an Affirmative Action institution. This material may be available in alternative formats.

This work is supported in part by Extension Implementation Grant 2021-70006-35390/ IND90001518G-1027053 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture and NCR SARE Award GNC20-311.

765-494-8491

www.extension.purdue.edu

Order or download materials from www.the-education-store.com