The Farming for a Better Climate series explored a variety of climate-smart agricultural practices that aim to maintain, or even increase, farm profitability while also slowing climate change. Topics focused on managing the soil’s carbon, soil conservation strategies, fertilizer stewardship, livestock and manure management, carbon markets, and energy use. Let’s review.

As we manage the soil, we also manage the climate. That’s because the soil contains most or all of the soil’s carbon – carbon that would otherwise be in the atmosphere trapping heat. Managing soil organic matter (SOM) also builds the soil’s resiliency to weather and climate extremes, like droughts and heavy rainfall, by increasing moisture-holding capacity. By implementing conservation practices, you can improve soil health, reduce soil erosion and nitrogen loss, and increase yields all while generating economic returns and helping the climate.

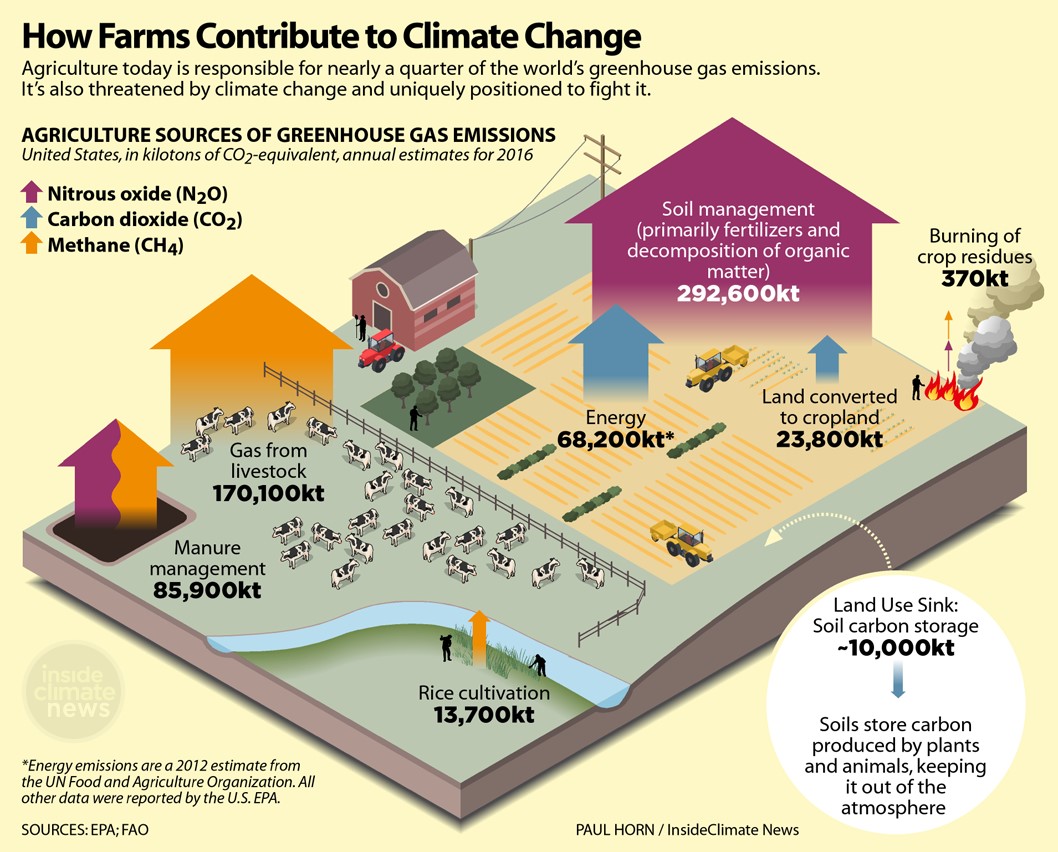

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, the majority of on-farm greenhouse gas emissions come from soil management. Adopting the 4R’s of Nutrient Management (Right Source, Right Rate, Right Time, and Right Place) can help optimize nutrient use and reduce negative environmental impacts. The Tri-State Fertilizer Recommendations for Corn, Soybeans, Wheat, and Alfalfa and the Fertilizer Institute’s Nutrient Stewardship are excellent resources for getting started with the 4R’s.

Reducing methane emissions in livestock production is of high interest. Researchers are exploring feed additives to reduce the amount of methane produced in a cow’s digestive tract with limited success. The tricky part is figuring out ways to decrease the methane output without killing important microbes in rumen. The most promising additives appear to be lemongrass, peppermint, garlic, and seaweed, but none are a silver-bullet additive solution at this point.

Manure management is another focal point for reducing methane. Generally, animal manure is placed in pits or lagoons, composted, or hauled off-site and spread onto agricultural fields. Anaerobic digesters on confined feeding lots are an expensive, but potentially lucrative, option for controlling animal waste. The end product, biogas, can be converted to natural gas and reused for fuel. Lagoon cover digesters or lagoon additives can also reduce emissions.

Some farmers are starting to venture into “carbon farming.” Companies are paying farmers to store additional carbon in their soil through conservation practices such as no-till and cover cropping, which in return will help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Economists at Purdue University recently wrote an article titled “Opportunities and Challenges Associated with Carbon Farming for U.S. Row-Crop Producers” that helps explain current carbon market options and requirements.

Reducing the amount of energy being used, using energy more efficiently, and incorporating energy from renewable sources are ways that farmers can lower their on-farm expenses while also helping the planet. The Extension Foundation has created a comprehensive suite of online fact sheets, case studies, decision tools, and worksheets to address farm energy use, conservation, and efficiency.

There are many paths to farming for a better climate, and farmers are already doing some of these. We hope you found this series interesting and informative. Purdue Extension, the Indiana State Climate Office, and the Purdue Climate Change Research Center appreciate you following along and we hope that you continue moving forward with farming for a better climate. You may review the suite of articles at the Indiana State Climate Office’s Farming for a Better Climate website.

Farms in the US release three main heat-trapping gases: nitrous oxide, methane, and carbon dioxide. The arrows in this graphic show the agricultural activities that release each of these gases. The width of each arrow shows how much each practice contributes to climate change. The largest contribution comes from wet, fertilized soils, which release nitrous oxide. Most of these emissions happen in the spring, before germination or when plants are still small. The second largest source is methane belched up by livestock. This graphic originally appeared in Why Farmers Are Ideally Positioned to Fight Climate Change published by Inside Climate News (8/24/2018).

Geothermal energy can be used to heat and cool buildings and homes using heat pumps that take advantage of stable ground temperatures deep in the earth. These systems are notably more expensive than natural gas and/or propane systems for regulating building temperatures, but the energy efficiency is much higher. Biomass energy involves plant and animal materials that either pull oils and sugars from plants to fuel vehicles (biofuels) or the burning of biomass (biopower). Biodigesters employ microorganisms to decompose biomass (most commonly livestock manure) and produce biogas, which can generate cleaner fuel for engines, electricity production, air and water heating, and refrigeration. Additional renewable energy resources can be found on the Extension Foundation’s Farm Energy resource page.

Farming for a Better Climate is written in collaboration by the Purdue Extension, the Indiana State Climate Office, and the Purdue Climate Change Research Center. If you have questions about this series, please contact in-sco@purdue.edu.