Turfgrass Insects

Integrated Management of Turfgrass INSECTS

Douglas Richmond, Turfgrass Entomology Extension Specialist

If you want to view as pdf, click here

HOW TO USE THIS PUBLICATION

The goal of this publication is to provide property owners and turfgrass management professionals with basic information to: 1) properly identify the most common turfgrass insect pests of Indiana and adjacent states, 2) recognize insect damage, 3) understand insect biology and 4) formulate safe and effective pest management strategies. For information on turfgrass identification, weed, disease and fertility management, visit the Purdue Turfgrass Science Website (http://turf.purdue.edu) or call Purdue Extension (1-888-EXT-INFO).

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT

While many different insects are associated with turfgrass, a few common insect species are responsible for the vast majority of insect damage. In fact, a square meter of healthy turfgrass typically contains thousands of insects and other arthropods, most of which are beneficial. The diverse forms of animal life found in turfgrass perform a variety of important functions including decomposition of dead plant material necessary for proper nutrient cycling and natural control of insect pests through predation or parasitism.

The primary challenge for turfgrass managers is striking a balance between the functional and aesthetic requirements of the turf and maintaining an environment that is suitable for beneficial organisms and the services they provide. Sound cultural practices that promote healthy, vigorous turf capable of tolerating or quickly recovering from insect damage form the foundation of an approach called “integrated pest management” (IPM). The goal of IPM is not to eliminate insects, but to keep insect pests below damaging levels. When properly implemented and aligned with user needs and expectation, IPM can achieve the manager’s goals while minimizing pesticide use and costs. The likelihood and/or severity of insect damage can be significantly reduced by:

1) Selecting turfgrass species and cultivars that are well adapted for a specific site or use

2) Proper mowing, fertilization, irrigation, thatch management and cultivation.

Insect-Resistant Plants

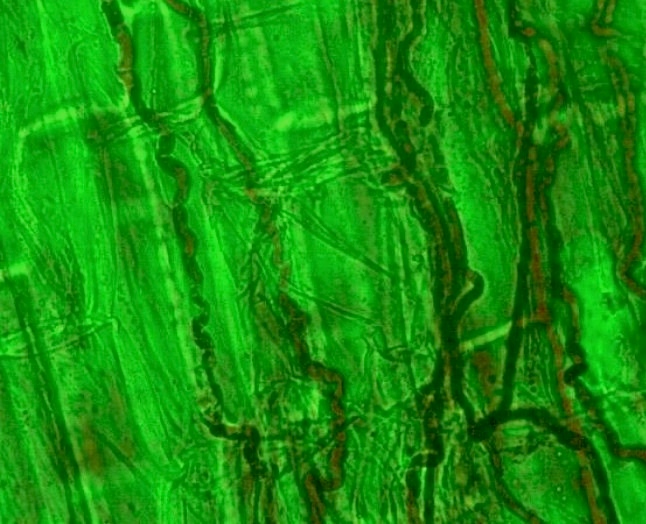

Certain turfgrass species and cultivars are resistant to attack by insect pests. In particular, endophyte-enhanced (E+) turfgrasses, including many cultivars of perennial ryegrass, tall fescue and creeping red fescue harbor microscopic fungi (Neotyphodium spp.) that deter above-ground insects (Fig. 1). These cultivars also benefit from improved tolerance to environmental stresses such as heat and drought and they can greatly reduce reliance on insecticides. However, because the fungi are located above-ground in the green, leafy portions of the plant, they have little activity against below-ground insects. E+ turfgrasses varieties also may be toxic to livestock and grazing wildlife, and should not be planted where the well-being of these animals is a concern. The seeds of E+ varieties come infected with the fungus and can be planted just as normal varieties. The availability of fresh seed is an important consideration when planting E+ varieties because endophyte viability can decrease rapidly when seeds are stored for an extended period of time, or at high temperatures. Endophyte infection rates of 40% or higher are generally recommended for providing insect resistance, but reliable estimates of infection must be assessed in living plants. Infection rates measured in the seed only provide an estimate of initial infection; viable infection may actually be much lower. For a list of E+ turfgrass cultivars and initial endophyte infection rates measured in the seed, see http://www.ntep.org/endophyte.htm.

Figure 1. The fungal endophyte Neotephodium coenophialum in tall fescue. Note the darker stained fungal hyphae growing between the plant cells.

Biological/Biorational Insecticides

Biologically-based insecticides can provide growers and managers with commercially available, sustainable alternatives for controlling turfgrass insect pests. These products include the insect-parasitic nematodes Heterorhabditis bacteriophora and Steinernema carpocapsae (Fig. 2), the insect-pathogenic bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis kurstaki, Bacillus thuringiensis galleriae, Paenibacillus popilliae, and the bacterial fermentation product, spinosad. When used properly, these products can be very effective and are generally safer than chemical insecticides. However, special considerations are sometimes required when storing or using these products. The amount of time required to reduce pest populations is often longer than with chemical insecticides and biological controls are often more expensive.

Figure 2. Infective juvenile of the insect parasitic nematode Steinemema carpocapsae, a common biological contgrol agent of above-ground turfgrass insects.

THE TARGET ZONE CONCEPT

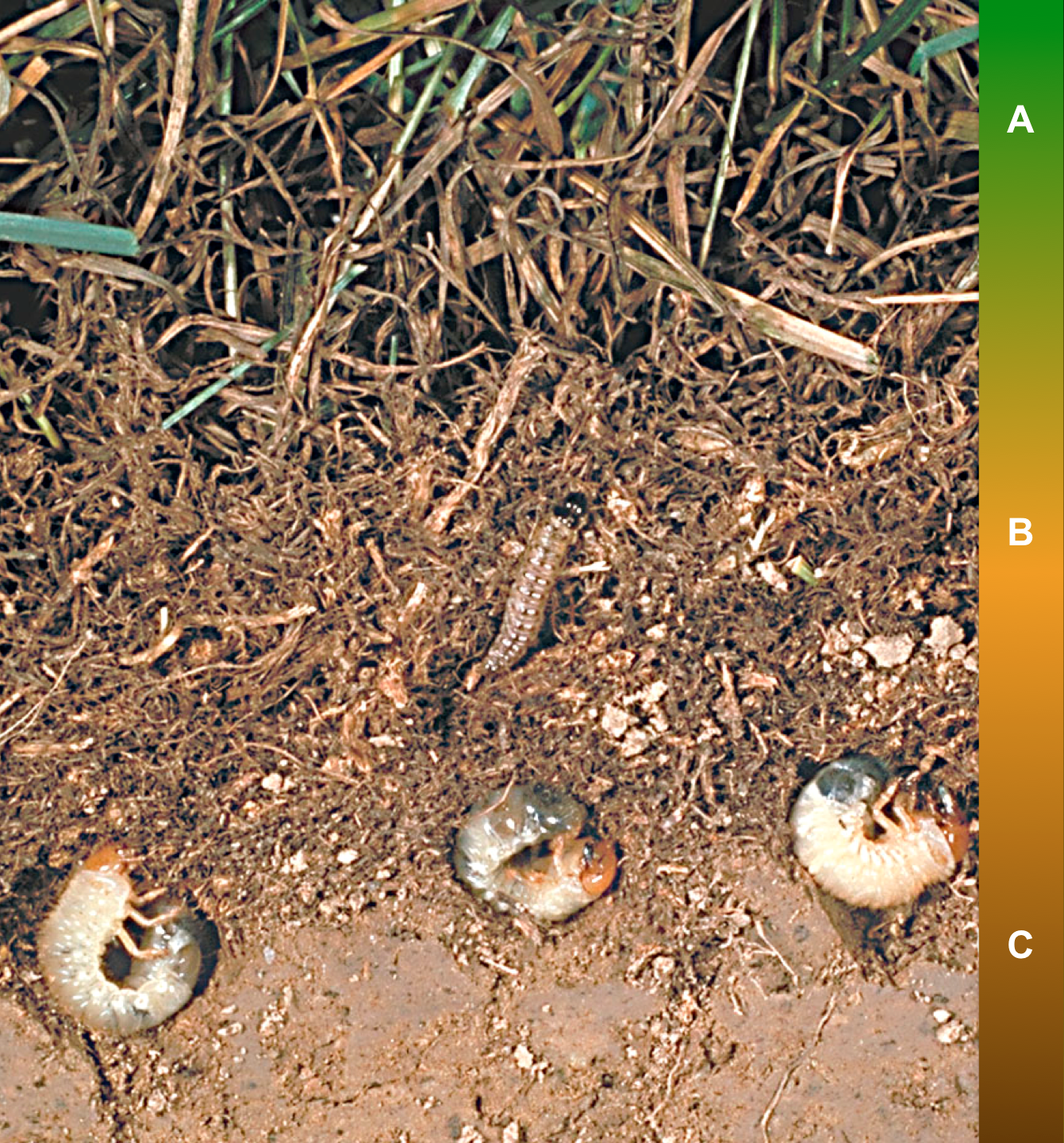

Knowing the specific portion of the turfgrass habitat occupied by a particular insect pest is essential for proper monitoring, diagnosis and management. Turfgrass insects can be broadly grouped according to where they reside within the turf profile; above- or below-ground . Above-ground pests include caterpillars, billbugs and chinch bugs that feed on the stems, crowns and leaves of plants. Many of these insects are closely associated with the thatch layer that provides cover for them during the day. Below-ground insects primarily consist of white grubs that damage plant roots as they feed in the soil.

Figure 3. Cross-sectional view of the turfgrass environment and representative insect pests. Note the three distinct target zones; A) stem and leaf, B) thatch, and C) soil. Insects inhabiting zones A and B are considered above-ground insects whereas those inhabiting zone C are below-ground insects.

Detection

Early detection of an insect infestation can be accomplished using a systematic approach that combines broad scale, coarse inspection of general turf appearance with fine scale inspection of individual plants or plant parts. If turf appears wilted, discolored or thin upon coarse inspection, examine suspect areas more closely by looking for feeding scars, tattered foliage or discoloration. Probe the margins of damaged patches of turf by scratching through the thatch and looking for movement. Green fecal pellets also may be present and can indicate the presence of foliage-feeding insects, especially caterpillars. Examine plant crowns by pulling on dead or damaged tillers (shoots or stems). If tillers dislodge easily, examine the bottom ends for the presence of fine, powdery, sawdust-like material indicative of billbug activity.

The use of a disclosing solution (1 tablespoon of Joy® Ultra, Dawn® Ultra or Ivory® Clear liquid dishwashing detergent in 1 gal. of water per 1 square yard of turf) poured over the surface of infested turf (Fig. 4) will encourage caterpillars to come to the surface where they can be collected and identified (do not use Palmolive® as it may burn the turf). Below-ground insects can be found using a golf course cup-cutter (Fig. 5) or a sturdy knife to cut a wedge of turf and carefully breaking apart the soil to a depth of 3 inches. Turfgrass that is severely damaged by soil insects will sometimes pull free from the soil and may be rolled-back like a rug, exposing the insects beneath (Fig. 6). It is important to keep in mind that some above-ground insects are only active at night and may be challenging to find during the day. Also remember that the presence of a pest insect is not necessarily cause for concern. Relatively high densities are usually required to cause significant damage.

Figure 4. Using a disclosing solution made by mixing 1 tablespoon of liquid dishwashing detergent in 1 gallon of water to flush above-ground insects from the thatch for detection.

Figure 5. Using a golf course cup-cutter to extract turf and soil cores for detection of below-ground insects.

Figure 6. Turfgrass sod peeled back exposing the soil-in-habiting white grubs beneath.

Proper Diagnosis

Selection of unsuitable turfgrasses, improper mowing, misuse or misapplication of pesticides and fertilizers, vandalism, damage from pets (or pet urine) and salt may cause damage that resembles insect feeding. For this reason, finding the insects responsible for damage provides the most dependable diagnosis. Proper diagnosis ensures that the proper course of action is taken to provide a solution. Knowing where to look and what to look for will increase your chances of making a proper diagnosis. Attributing damage to insects when no insects can be found can lead to unnecessary insecticide applications, exposure risks and expense. Keep in mind that most insects associated with turfgrass are either beneficial or inconsequential. Others may be an occasional nuisance, but pose no serious threat to turf.

Using Insecticides

Understanding the target zone concept is also important when using insecticides. Insecticide residues should remain in the target zone for as long as possible in order to provide the greatest opportunity for the target insect to contact or ingest the insecticide. For insects that feed on leaves and stems, the insecticide residue should remain above-ground on the vegetation or in the thatch. Liquid materials should not be irrigated for at least 24 h after application, whereas granular formulations should be irrigated only enough to release the active ingredient from the granule. Always refer to the product label for guidance on this matter. For soil insects, irrigation or rainfall is usually recommended as soon as possible after application in order to wash the active ingredient into the soil where the insects are feeding. Since insecticides are toxic to honeybees and other pollinating insects, they should not be applied to turfgrass that contains flowering weeds. For more information on pollinator safety and insecticide use see http://extension.entm.purdue.edu/neonicotinoids/ or E-267-W Protecting Pollinators from Insecticide Applications in Turfgrass.

If insects are found damaging turf, or in sufficient numbers to warrant concern, a variety of cultural, biological and chemical management options are available. Although chemical tools will often provide the most immediate solution, cultural and biological options may provide a more long-term, sustainable solution and should always be considered as part of an integrated management program. Optimal irrigation, fertilization and mowing heights may help reduce the severity of insect damage and facilitate regrowth and recovery when damage does occur.

Table 1 (last page) contains a list of common chemical and biological/biorational insecticides recommended for control of the most common turfgrass pests. Efficacy data for various active ingredients is generated regularly by the Turfgrass Entomology and Applied Ecology Laboratory in the Department of Entomology at Purdue University and summaries of these data are available in order to help managers make informed decisions: http://www.turf.purdue.edu/research-annual-report.html. Always read and follow label directions.

Evaluating Insecticide Applications

Insecticides are designed to kill insects and can not bring dead grass back to life. While killing insect pests may prevent further damage, one should not necessarily expect immediate improvement in the appearance of the turf. Even under optimum growing conditions, turf may require several weeks to recover and, if damage is severe, renovation may still be required.

After applying an insecticide, it is a good idea to evaluate performance. Although some insecticides may kill the target insects within a relatively short period of time (2 to 3 days), others may be slower acting (2 to 3 weeks), especially when below-ground insects are the target. It is not unusual for biological insecticides to take longer than chemical insecticides to attain maximum efficacy. When a treatment fails to provide expected results, try to determine the cause. Most insecticide failures can be attributed to the following causes.

- Improper calibration or poorly maintained equipment. Equipment should be recalibrated each season. Since every formulation behaves differently, each must be calibrated individually. The labels of homeowner/garden center formulations often contain suggested settings for a range of common application equipment, but equipment must be properly maintained and in good working order for these recommendations to apply.

- Improper timing. Insecticides applied during the wrong time of the season are seldom effective. Insects are vulnerable to insecticides only during key points in their life cycle. It is important to make sure insects are either present or will soon be present in the susceptible stage before applying insecticides. In the case of white grubs, insecticide applications are most effective when they coincide with activity of early instar (young) grubs that are higher in the soil profile.

- Improper irrigation. The labels on most white grub insecticides recommend irrigating with at least 1/4 inch of water immediately after application. This procedure helps wash the chemical off of the granule when a granular formulation is used, or off of the grass canopy when a liquid formulation is used. It also helps to rinse the active ingredient into the soil where the grubs are actively feeding. A small amount of irrigation or rainfall is always recommended following application of a granular formulation, regardless of the target insect species, in order to release and distribute the active ingredient. Liquid applications targeting surface insects should be left on the surface (not irrigated) for at least 24 hours following application in order to maximize efficacy.

- Tank hydrolysis. This is mainly a concern for operations that require large amounts of material to be prepared. When mixed with water that has either a high or a low pH, some insecticides will begin to break down inside the holding tank. To minimize tank hydrolysis, check the pH of the water used to mix the spray solution and adjust the pH accordingly with a buffer or water conditioner. Mix only what is required, and do not store spray solutions. For more detailed information on this subject, see The impact of water quality on pesticide performance https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/PPP/PPP-86.pdf.

BELOW-GROUND PESTS

White Grubs

White grubs are the immature stage (larva) of several beetle species including Japanese beetle Popillia japonica, masked chafers Cyclocephala borealis and Cyclocephala lurida, Green June beetle Cotinus nitida (Linnaeus), black turfgrass ataenius Ataenius spretulus, and May or June beetles Phyllophaga spp. In addition, three other species (European chafer Rhizotrogus majalis, Oriental beetle Anomala orientalis, Asiatic garden beetle Maladera castanea) have recently been introduced into the state of Indiana (see New White Grub Pests of Indiana - E-259). The grubs are white, C-shaped insects with a chestnut colored head and 3 pairs of legs that are clearly visible. The rear end is slightly larger in diameter than the rest of the body and may appear darker in color due to the soil and organic matter they ingest. Size may vary considerably depending on the species and age, but late instar (older) larvae will generally range from 1/4 to 1-1/2 inches in length.

White grubs begin feeding immediately after hatching, which usually occurs during July for the most common species. Depending on the species involved, grubs may feed and develop for a single year (Japanese beetle, northern and southern masked chafers, European chafer, Oriental beetle, Asiatic garden beetle, green June beetle), several years (May or June beetles), or they may complete their entire life cycle in less than one year (black turfgrass ataenius). Close examination of the pattern of hairs and spines present on the underside of the abdomen (raster) (Fig. 7), using a hand lens or magnifying glass, is usually required to identify white grubs to species. Although the adult forms (beetles) may feed on other plant species, they do not feed on turfgrass.

Figure 7. A typical soil-inhabiting white grub with C-shaped body form and clearly visible legs. Yellow arrow indicates location of the raster useful for identifying white grubs to species.

Grubs feeding on the root system of grass plants cause the most serious insect-related injury to Indiana turfgrass. Symptoms of white grub damage usually begin with wilting of the grass and lack of recovery after irrigation or rainfall. Severe damage results in dead patches of turf and is usually noticed during late summer and fall although it may also occur in the spring, particularly in areas where European chafer is present. This kind of damage, called primary damage, may result in sod that easily pulls-up or becomes dislodged from the soil (like a rug), revealing the white grubs beneath. Secondary damage from raccoons, skunks, or flocks of birds foraging for the grubs is also common and can sometimes be the first obvious indication of a grub infestation. For more information on the biology and management of white grubs in turfgrass, see E-271-W Managing White Grubs in Turfgrass https://extension.entm.purdue.edu/publications/E-271/E-271.html.

ABOVE-GROUND PESTS

Armyworms

Armyworms are the immature stage (larva/caterpillar) of the several widely distributed moth species. Species most often associated with turfgrass include the common armyworm Mythimna unipuncta (Fig. 8), fall armyworm Spodoptera frugiperda (Fig. 9) and yellowstriped armyworm Spodoptera ornithogalli. These insects are better known as pests of agricultural crops, but they sometimes infest turfgrass, especially in areas that border agricultural fields or unmanaged areas such as ditches or fencerows. Outbreaks in turf tend to be patchy and sporadic, but sometimes occur on a larger scale. As their name implies, armyworms may occur en masse and can migrate across large areas of turf, cutting it down to crown level as they go. Because they often go unnoticed while they are small, turf may seem to disappear almost overnight once these insects reach a larger size. Small patches of brown and overall ragged appearing turf are more typical symptoms. Fortunately, unless the turf is severely stressed by drought, it generally recovers well with irrigation or rainfall and adequate fertility.

Figure 8. Common armyworm caterpillar with lengthwise brown and/or yellow stripes.

Figure 9. Fall armyworm caterpillar with lengthwise stripes and inverted Y-shape on head. (Photo Credit: J. Obermeyer).

Cutworms

Cutworms are also the immature stage (larva/caterpillar) of several moth species, but only two species are typically associated with turfgrass. The black cutworm Agrotis ipsilon (Fig. 10). The black cutworm is primarily a pest of closely mowed, golf course turf where it creates unsightly pock-marks or depressions in highly manicured playing surfaces. Black cutworm damage interferes with play and can be a serious nuisance to golfers, especially with regard to their “short game”. For more information on the biology and management of black cutworms, see E-270-W Managing Black Cutworms in Turfgrass https://extension.entm.purdue.edu/publications/E-270/E-270.html.

Figure 10. Black cutworm caterpillar and damage on bentgrass.

The bronze cutworm Nephelodes minians (Fig. 11) is a more sporadic pest of lawns and low maintenance turf. Bronze cutworm has a penchant for feeding on turf under the cover of snow and damage from this insect is often unnoticed until after the snow melts and turf begins to green-up. Damage rarely occurs after mid-June.

Figure 11. Bronze cutworm caterpillar with alternating dark and light lengthwise stripes.

Sod Webworms

Sod webworms are the immature stage (larva/caterpillar) of several small buff-colored moths that are common during the summer months. The moths are easily observed as they fly from the turf when disturbed, only to light again several yards away where they typically align themselves lengthwise along a blade of grass. They roll their wings close around the body when at rest and they posses an elongated snout that gives their heads a conical appearance. Adults do not feed, but mate and drop their eggs into the turf canopy during the evening. Larvae (Fig. 12) overwinter in silken tunnels and emerge in the spring to feed on grass stems crowns and leaves. Damage usually occurs in sunny areas and may appear as irregular, brown patches that take on a thin or ragged appearance during the summer. On short-cut golf course turf, overwintered larvae may attract attention due to their habit of knitting together small pieces of debris or topdressing material over the entrances to their burrows. Two to three generations of sod webworms may occur each season.

Figure 12. Sod webworm caterpillar with rows of dark, square spots.

Billbugs

Like most weevils, adult billbugs can be distinguished from other turfgrass pests by their long snout (Fig. 13). Although these insects comprise a complex of at least 4 species, only two species typically damage turfgrass in the Midwest. The bluegrass billbug Sphenophorus parvulus is the most common species found in cool-season grasses such as Kentucky bluegrass, perennial ryegrass, and fescue whereas the hunting billbug Sphenophorus venatus is usually associated with warm-season grasses such as zoysiagrass and Bermudagrass. Adults feed primarily on the stems (tillers) and leaves of plants and don’t usually cause noticeable damage. The white, legless larvae (Fig. 14) however, feed on and inside the stems, crowns, rhizomes and stolons of plants and may cause considerable damage. Damage first appears in the form of small dead spots that are sometimes visible by mid-June. Under dry conditions, these spots may coalesce into large irregular patches. Damaged stems may break-off or pull from the soil with minimal pressure, often exposing a fine, powdery, frass. For more information on the biology and management of billbugs, see E-266-W Managing Billbugs in Turfgrass https://extension.entm.purdue.edu/publications/E-266/E-266.html.

Figure 13. Bluegrass billbug adult with long snout and rows of fine punctures along its back.

Figure 14. Billbug larva in soil. Note that the larva is legless.

Chinch Bugs

Adult chinch bugs are small (1/6 inch), black and white insects that move about quickly when disturbed. Their wings may be shorter than their body and are typically marked with a small black triangular shape along the outside margins. Immature chinch bugs (nymphs) are similar in shape to the adults, but are usually bright orange or red in color and wingless, with a broad white band across the their back (Fig. 15). Only one species, the hairy chinch bug Blissus leucopterus hirtus, infests turfgrass in Indiana and adjacent states. Chinch bugs are often found at the margin between damaged and healthy grass and will release a pungent defensive odor when disturbed. Nymphs and adults damage turfgrass by sucking fluids from plant vascular tissues and by injecting saliva that destroys these vascular tissues. For this reason, plants may appear to die from the top down, turning yellow and then brown as feeding continues. Chinch bugs overwinter as adults and produce two generations each year.

Figure 15. Chinch bug nymphs with bright orange bodies and broad white band across the back (Photo Credit: J. Obermeyer).

| Table 1. Active ingredients of insecticide products recommended for use in turfgrass and common insect control. |

|---|

| Insecticide* (Trade Name/Manufacturer) |

Insecticide Class | White Grubs | Billbugs | Caterpillarsa | Chinch Bugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permethrin (Astro/FMC) |

Pyrethroid | Xb | X | ||

| Beta-cyfluthrin (Tempo/Bayer) |

Pyrethroid | Xe | X | X | |

| Bifenthrin (Talstar/FMC) |

Pyrethroid | Xe | X | X | |

| Carbaryl (Sevin/Bayer; others) |

Carbamate | X | X | X | X |

| Chlopyrifosc (Dursban/Dow) |

Organophosphate | < | X | X | X |

| Chlorantraniliprole (Acelepryn/Syngenta; others) |

Diamide | X | X | X | |

| Cyantraniliprole (Ference/Syngenta) |

Diamide | X | X | X | |

| Clothianidin (Arena/Nufarm; others) |

Neonicotinoid | X | X | X | X |

| Deltamethrin (DeltaGard/Bayer; others) |

Pyrethroid | Xe | X | X | |

| Dinotefuran (Zylam/PBI-Gordon) |

Neonicotinoid | X | X | X | |

| Imidacloprid (Merit/Bayer, others) |

Neonicotinoid | X | X | ||

| Indoxacarb (Provaunt/Syngenta) |

Oxadiazine | X | |||

| Lambda-cyhalothrin (Scimitar/Syngenta) |

Pyrethroid | Xe | X | ||

| Thiamethoxam (Meridian/Syngenta) |

Neonicotinoid | X | X | X | X |

| Trichlorfon (Dylox/Bayer) |

Organophosphate | X | X | X | X |

| Zeta-cypermethrin (Talstar Xtra/FMC) |

Pyrethroid | Xe | X | X | |

| *Always consult label directions for specific timing and application recommendations. aCaterpillars=armyworms, cutworms, and sod webworms. bLabeled only for use against sod websorms caterpillars. cLabeled only for use on turfgrass grown for sod or seed. dRecommended for billbug larvae only. eRecommended for billbug adults only. fRecommended for Japanses beetle larvae only. |

|||||

| Table 1 (continued). Active ingredients of insecticide products recommended for use in turfgrass and common insect control. |

|---|

| Insecticide* (Trade Name/Manufacturer) |

Insecticide Class | White Grubs | Billbugs | Caterpillarsa | Chinch Bugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus thuringiensis (kurstaki) (Dipel/Valent; others) |

Microbial | Xb | |||

| Bacillus thruingiensis (galleriae) (GrubGONE G/Phyllom) |

Microbial | X | |||

| Paenibacillus popilliae (Milky Spore/St. Gabriel; others) |

Microbial | Xf | |||

| Heterorhabditis bacteriphora (Nemasys G/BASF; others) |

Parasitic nematode | X | Xf | ||

| Spinosad (Conserve/Dow) |

Biorational | X | |||

| Steinernema carpocapsae (Millenium/BASF; others) |

Parasitic nematode | Xc | X | X | |

| *Always consult label directions for specific timing and application recommendations. aCaterpillars=armyworms, cutworms, and sod webworms. bLabeled only for use against sod websorms caterpillars. cLabeled only for use on turfgrass grown for sod or seed. dRecommended for billbug larvae only. eRecommended for billbug adults only. fRecommended for Japanses beetle larvae only. |

|||||

READ AND FOLLOW ALL LABEL INSTRUCTIONS. THIS INCLUDES DIRECTIONS FOR USE, PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS (HAZARDS TO HUMANS, DOMESTIC ANIMALS, AND ENDANGERED SPECIES), ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS, RATES OF APPLICATION, NUMBER OF APPLICATIONS, REENTRY INTERVALS, HARVEST RESTRICTIONS, STORAGE AND DISPOSAL, AND ANY SPECIFIC WARNINGS AND/OR PRECAUTIONS FOR SAFE HANDLING OF THE PESTICIDE.

August 2016

It is the policy of the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service that all persons have equal opportunity and access to its educational programs, services, activities, and facilities without regard to race, religion, color, sex, age, national origin or ancestry, marital status, parental status, sexual orientation, disability or status as a veteran. Purdue University is an Affirmative Action institution. This material may be available in alternative formats.

This work is supported in part by Extension Implementation Grant 2017-70006-27140/ IND011460G4-1013877 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

1-888-EXT-INFO

www.extension.purdue.edu

Order or download materials from www.the-education-store.com