PUBLIC HEALTH

HUMAN LICE: BIOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH RISK

Catherine A. Hill and John F. MacDonald, Department of Entomology

If you want to view as pdf, click here

Lice are parasitic insects that must live, feed, and reproduce on the body of a living host. Numerous information sources discuss the lice that are parasites of humans, their public health risk, methods of personal protection, and approaches to control. You are encouraged to learn more about the biology of human lice to help you make more informed decisions about health risks, how to prevent infestations, and where to find information about the control of human lice.

Are Human Lice a Public Health Risk?

Human lice are blood-sucking nuisances and a cause of social embarrassment. In the U.S., the head louse is by far of greatest imortance because of its common and widespread occurrence, especially among children. None of the human lice are known to be vectors of disease agents in Indiana.

In other regions of the world, the body louse is the vector of three diseases. Historically, epidemic typhus fever and epidemic relapsing fever have caused devastating outbreaks, primarily associated with disasters such as war, but also with natural disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes. The third disease transmitted by body lice is a non-fatal infection known as “trench fever.” All three diseases are associated with situations in which humans are crowded together under conditions where sanitation is severely limited or non-existent.

How Many Types of Lice Are Parasites of Humans?

There are three types of human lice: the head louse, the pubic louse, and the body louse. As the common names imply, each type typically infests a specific area of a human (see below). Scientists who study lice differ in their opinion regarding the body louse and the head louse. Some authorites consider them to be two subspecies of Pediculus humanus because they can interbreed to produce fertile offspring in the laboratory, and they are nearly identical in appearance. In this viewpoint, the body louse is named Pediculus humanus humanus and the head louse is named Pediculus humanus capitis.

Other authorities consider the body louse and the head louse to be two separate species because they rarely interbreed on human hosts on which both co-exist. In this viewpoint, the body louse is named Pediculus humanus and the head louse is named Pediculus capitis. In addition to being very distinct in body form, the pubic louse cannot interbreed with the body louse or the head louse, and is considered by all to be a distinct species with the scientific name Pthirus pubis.

Lice Parasites of Animals Other Than Humans

Parasitic lice belong to the insect order Phthiraptera and include two main groups. The group that includes the human lice is known collectively as “Anoplura,” or the sucking lice. There are over 550 species in the world, all of which are blood-sucking parasites of mammals, including wildlife, livestock, and pets.

The second group contains the chewing lice, known collectively as “Mallophaga.” This is a large and diverse assemblage of over 2, 650 species in the world, none of which suck blood. Instead, they possess weak chewing mouthparts and feed on feathers, fur, and skin debris on their host. About 85% of the chewing lice are parasites of birds, including poultry. About 15% are parasites of mammals, including livestock and pets, but not humans.

Parasitic Lice and Their Hosts

Parasite lice are highly “host-specific,” which means that they typically live, feed, and reproduce on a single species of animal. Lice that are parasites of dogs, cats, guinea pigs, birds, and livestock do not feed and do not reproduce on humans. These lice very rarely transfer to a human, and they die within a few hours or so if they happen to get on our bodies. This is why pets and livestock that are infested with lice are not a source of louse infestation to infants, young children, and adults.

How Can I Recognize the Three Types of Human Lice?

As a general rule, the three types of human lice can be distinguished by where they occur on the body, as suggested by their common names. Adults of the head louse and the body louse are nearly identical in appearance (Fig. 1), with both being about 1/8 inch long, cylindrical, and grayish-white when unfed. Adults of the pubic louse (Fig. 2) resemble miniature crabs in possessing relatively huge front legs and a somewhat crab-shaped body. This is why the pubic louse is also known as the “crab louse,” and an infestation is known as “crabs.”

Immature human lice are known either as “larvae” or “nymphs,” and they resemble the corresponding adults, but they are smaller and paler in color. Larvae and adults of human lice are wingless and have three pairs of legs. They have a short, slender proboscis (beak) that is retracted within their head and extended only when they take a blood meal.

The head louse. (Photo Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

The pubic louse. (Photo Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

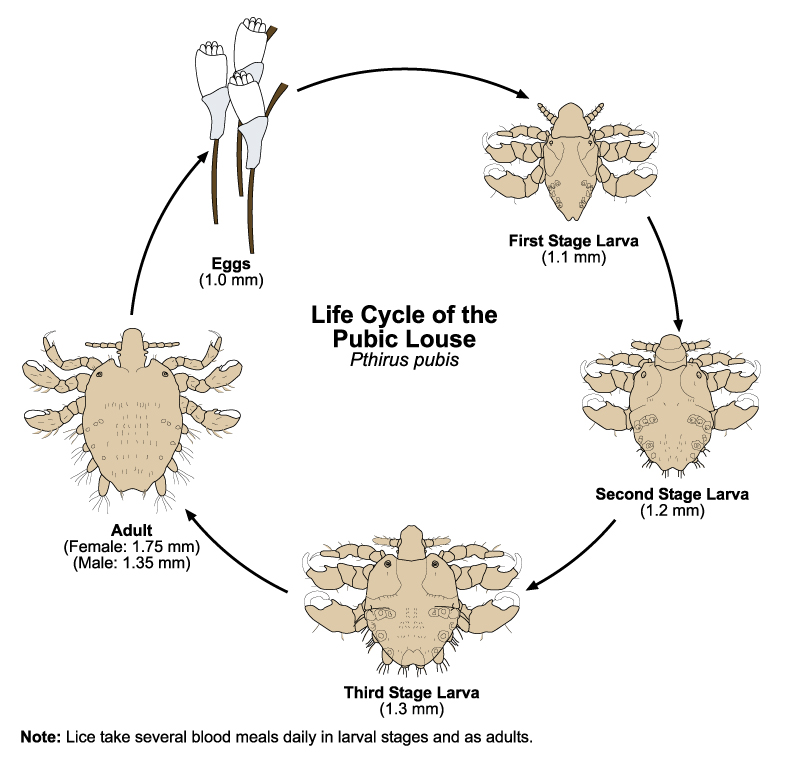

What Is the Life Cycle of Human Lice?

Human lice develop from an egg to an adult via a process of “gradual metamorphosis” (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). This means the last larval stage develops directly into an adult without passing through a non-feeding pupal stage. Human lice have three larval stages, and each requires blood meals before molting into the next life cycle stage. Both adult males and females feed on blood and take repeated blood meals about every 4-8 hours during their lives. Females require blood meals for the development of eggs, which commonly are known as “nits.”

Life cycle stages of the body louse (similar for the head louse) (Drawing credit: Scott Charlesworth, Purdue University, based in part on Kim, K.C., H.D. Pratt, and C.J. Stojanovich, 1986, The Tucking Lice of North America)

Life cycle stages of the pubic louse. (Drawing credit: Scott Charlesworth, Purdue University, based in part on Kim, K.C., H.D. Pratt, and C.J. Stojanovich, 1986, The Sucking Lice of North America)

All life cycle stages of human lice require a live human host on which to develop. Larvae and adults typically die within a day or two if they fall off a host because they require the temperature and relatively high humidity provided by the human body. Female head lice and pubic lice glue their eggs onto the base of hairs of their host. In contrast, female body lice glue their eggs primarily onto fibers of clothing worn by an infested person, but on occasion glue them onto the base of hairs of the host. Eggs of head lice can remain viable for several days after infested head hairs fall off a host and may hatch if they experience adequate warmth and humidity inside a dwelling.

Each of the three larval stages is completed in 3-8 days. Adult females live up to 35 days and can lay up to three eggs per day. Under optimal conditions, the body louse can complete 10-12 generations per year and has the potential to develop very large numbers in groups of infested humans. Compared to the body louse, the head louse and the pubic louse take longer to complete a life cycle, have fewer generations per year, and typically do not infest humans in large numbers.

How Can I Recognize a Human Louse Infestation?

Human lice suck blood and in the process inject saliva that contains chemicals that cause an inflammatory response. As a consequence, itching in the area is an initial symptom of an infestation. Close inspection usually reveals the presence of active lice on the body or in clothing in the case of the body louse. Further inspection may reveal the existence of louse eggs glued to body hairs or in the seams of clothing in the case of the body louse.

What Types of Situations Favor the Spread of Human Lice?

Human lice have the potential to transfer from person to person very quickly. The head louse spreads from an infested person to others during direct contact and indirectly when infested items such as hats, scarves, coats, combs, and brushes are shared. School-age children are at risk because they are more likely to share such items, especially under crowded conditions. The pubic louse typically spreads between human partners during sexual intercourse and other intimate contact. Spread of pubic lice via infested bedding and toilet seats can occur, but is not common because pubic lice die within a few hours once they are off a human host.

The body louse spreads during direct contact with infested people or indirectly when infested clothing is shared. Body lice also spread when they leave a person with a high fever and crawl across a surface to infest a nearby individual. Again, the body louse is capable of rapidly building very high numbers and infesting large numbers of people living in conditions that are associated with disasters such as war, hurricanes, and earthquakes when humans are crowded together without access to clean clothes, clean bedding, and periodic bathing.

How Are Human Lice Controlled?

Control of human lice typically involves the use of an insecticide together with the mechanical removal of eggs and lice, plus sanitation of infested articles such as hair brushes, hats, scarves, clothes, and bedding. Insecticides known as “pediculicides” include over-the-counter products and physician prescribed medications. For information on controlling lice and for specific chemical control products refer to the Web site of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and discuss control options with a physician. It is essential to apply PRODUCTS exactly as directed on the LABEL AND as directed on the pREscription. In addition, it is important to note that eggs of human lice are not killed by insecticides, and a repeat application typically is required in 7-10 days in order to kill newly hatched larvae. Infested clothing and bedding should be washed at a minimum of 130°F and then dried at a high temperature for 20 minutes in a clothes dryer in order to kill lice and eggs. Items that cannot be washed require dry-cleaning.

Are Any Home Remedies Effective in Controlling Head Lice?

There is no evidence that any of the so-called “home remedies” control head lice. Recent research has shown that the following are of little or no effectiveness: vinegar, isopropyl alcohol, olive oil, mayonnaise, melted butter, and petroleum jelly (Fig. 5). Also, none of the tested materials killed head louse eggs. Additional research into the potential for “drowning” head lice showed that head lice survive being totally submerged in water for up to 8 hours.

Are Head Lice in Some Areas Resistant to Insecticides?

Resistance to approved, properly applied insecticides is a problem in the U. S., including Indiana, but the specific insecticide involved can differ from one area to another. If control is not successful after properly applying an approved insecticide, it may be possible to try an alternative insecticide. Consult with your local health care provider regarding alternatives that are effective in your area.

What Specific Things Should I Know About Human Lice?

Detailed information pertaining to the three types of human lice is summarized below in “bullet” form for quick reference and for making comparisons.

Head Louse

Geographical distribution of head lice

• World-wide, including all developed nations.

Special situations favoring head lice infestations

• Schools and day-care centers in which children are in frequent, close contact.

• Contact with infested clothing, hats, combs, scarves, audio devices, and cell phones.

Location of head lice infestations

• The fine hairs of the head, but occasionally in eyebrows.

• NOTE: Eggs are laid at the base of head hairs.

Spread of head lice

• Contact with infested people and infested items (see above).

Symptoms of head louse infestation

• Itching and irritability.

• Excessive scratching, resulting in scab-covered sores and secondary bacterial and fungal infections.

Public health risk of head lice

• Severe nuisances and social embarrassment.

• Potential for secondary infections associated with sores.

• NOTE: There is no known involvement of head lice as vectors of disease agents.

Control of head lice

• Avoid contact with infested people.

• Avoid contact with infested items.

• If possible, remove eggs and lice with fingers or a “nit” comb.

• For specific chemical control, refer to CDC recommendations and see a physician.

Figure 5. Home remedies that are not effective in controlling head lice. (Drawing credit: Scott Charlesworth, Purdue University)

Pubic Louse

Geographical distribution of pubic lice

• World-wide, including all developed nations.

Situations favoring pubic lice infestation

• Sexual activity with an infested partner.

Location of pubic lice infestations

• Typically on coarse hairs in the genital region of adolescents and adults.

• Occasionally in other locations such as eyelashes, eyebrows, and mustaches.

• NOTE: Pubic louse eggs are laid at the base of coarse body hairs.

Spread of pubic lice

• Primarily during sexual intercourse and other intimate activities.

• Potentially, but rarely, via infested bedding and toilet seats.

Symptoms of pubic louse infestation

• Itching and irritability.

• Excessive scratching, resulting in scab-covered sores and secondary bacterial and fungal infections.

Public health risk of pubic lice

• Severe nuisances and social embarrassment.

• Possibility of secondary infections associated with sores.

• NOTE: There is no evidence that pubic lice are vectors of disease agents.

Control of pubic lice

• Avoid sexual relations with infested partners.

• For specific chemical control, refer to CDC recommendations and see a physician.

Body Louse

Geographical distribution of body lice

• Temperate regions and high elevations of Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

Situations favoring body lice infestations

• Crowded and unsanitary conditions associated with disasters such as war, hurricanes, and earthquakes.

Location of body lice infestations

• On or in clothing, especially woolens.

• NOTE: Body lice typically do not live directly on the human body.

• NOTE: Eggs typically are glued onto clothing fibers, usually along seams, but occasionally on body hairs.

Spread of body lice

• Primarily via contact with infested people.

• Also via lice leaving a person with a high fever and crawling to a nearby individual.

• Potentially via contact with infested clothing and bedding.

Symptoms of body louse infestation

• Itching and irritability.

• Excessive scratching, resulting in scab-covered sores and secondary bacterial and fungal infections.

Public health risk of human body lice

• Severe nuisances and social embarrassment.

• Vectors of three different disease agents in certain regions of the world.

Control of body lice

• Avoid contact with infested people, clothing, and bedding.

• Infested items should be washed at 130°F. and dried in a clothes drier at high temperature.

• For specific chemical control, refer to CDC recommendations and see a physician.

Are There Any Louse-Borne Diseases of Humans In the U. S.?

There is no louse-borne disease at this time in the U.S. Body lice can be vectors, but they are not commonly encountered and rarely seen by the general public. World travelers can find details pertaining to louse-borne epidemic fever, epidemic relapsing fever, and trench fever in references listed below.

Where Can I Find More Information on Human Lice and Louse-Borne Diseases?

The following Web site contains accurate and current source of detailed information on human lice and louse-borne diseases.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention <https://www.cdc.gov>

A recent (2002) textbook by G. Mullen and L. Durden, Medical and Veterinary Entomology, has an excellent chapter devoted to lice and louse-borne diseases that covers biology, behavior, medical and veterinary risk, and general information on prevention and control.

READ AND FOLLOW ALL LABEL INSTRUCTIONS. THIS INCLUDES DIRECTIONS FOR USE, PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS (HAZARDS TO HUMANS, DOMESTIC ANIMALS, AND ENDANGERED SPECIES), ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS, RATES OF APPLICATION, NUMBER OF APPLICATIONS, REENTRY INTERVALS, HARVEST RESTRICTIONS, STORAGE AND DISPOSAL, AND ANY SPECIFIC WARNINGS AND/OR PRECAUTIONS FOR SAFE HANDLING OF THE PESTICIDE.

January 2019

It is the policy of the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service that all persons have equal opportunity and access to its educational programs, services, activities, and facilities without regard to race, religion, color, sex, age, national origin or ancestry, marital status, parental status, sexual orientation, disability or status as a veteran. Purdue University is an Affirmative Action institution. This material may be available in alternative formats.

This work is supported in part by Extension Implementation Grant 2017-70006-27140/ IND011460G4-1013877 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

1-888-EXT-INFO

www.extension.purdue.edu

Order or download materials from www.the-education-store.com