Rick Foster, Purdue Entomology; Bruce Bordelon, Peter Hirst, Purdue Horticulture and Landscape Architecture; Valerie Clingerman, Purdue Extension-Knox County; Michael O-Donnell, Purdue Extension-Delaware County' and Roy Ballard, Purdue Extension-Hancock County

If you want to view as pdf, click here

Most fruit and vegetable growers depend on pollinators to successfully produce their crops. Although most people think of honey bees when they hear “pollinators,” many insects and other animals pollinate flowers, including mason bees, bumble bees, flies, moths, butterflies, and hummingbirds.

All of these animals serve an important function as pollinators. They all visit flowers to feed on pollen or nectar. In the process, pollinators move pollen from one flower to another, eventually helping the flower produce seed and fruit. This pollination process is central to the well-being of our fruit and vegetable crops.

Crop plants vary in their dependence on pollinators. Table 1 summarizes the dependence of selected fruit and vegetable crops.

Table 1. The importance of pollinators in selected fruit and vegetable crop production.

| Crops That Require Pollinators | Crops That Don't Require Pollinators But Have Better Yields With Them | Crops From Which Pollinators Collect Pollen |

|---|---|---|

| melons cucumber squash/pumpkin tree fruits blueberry raspberry and blackberry strawberry |

eggplant lima bean okra pepper |

pea snap bean sweet corn tomato |

Today, honey bees and other pollinators face a number of stresses that are reducing their numbers. For honey bees, some of these stresses include Varroa mites, tracheal mites, small hive beetles, several diseases, and (in some cases) the stress from being transported long distances to provide pollination services to various crops.

Native pollinators suffer from the stresses of habitat loss from both agriculture and development. Habitat loss reduces the availability of suitable nesting sites and host plants to feed on.

Pesticides can harm all pollinators.

Figure 1. A dead honey bee on a blackberry leaf.

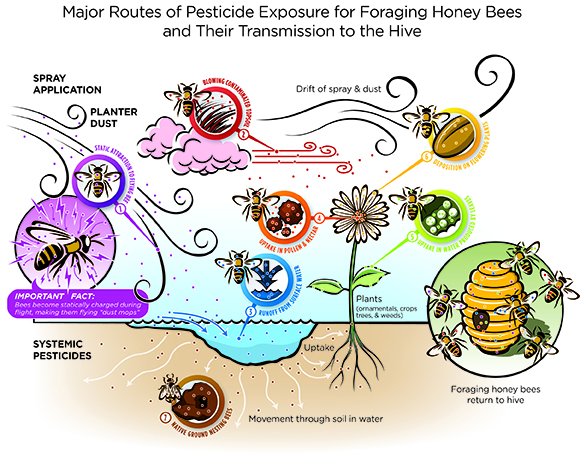

Figure 2. This illustration shows the major ways foraging bees are exposed to pesticides and transmit them to the hive.

A wide variety of insect pests attack fruit and vegetable crops. These pests can affect yields and consumers commonly demand blemish-free produce. So growers usually require insecticides to manage those pests.

Almost all insecticides used on fruit and vegetable crops have some toxicity to pollinators, and many of them are very toxic. For a fairly complete list of pesticides and their relative toxicity to pollinators, see Protecting Honey Bees from Pesticides (Purdue Extension publication E-53-W), available from the Education Store (edustore.purdue.edu). Although this publication specifically addresses honey bees, most insecticides have similar toxicity for other pollinators.

Even organic products come with risks. Some OMRI-approved organic insecticides (including neem and spinosad) are highly toxic to honey bees and other pollinators, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

In fruit and vegetable production, insecticides can harm pollinators (including bees) in several ways:

- Applicators apply insecticides to fruit or vegetables when pollinators are present, resulting in direct exposure. This can be true for crops that require pollination services and for crops where pollinators are only feeding on pollen.

- Applicators apply insecticides to fruit or vegetables when pollinators are not present, but the insecticide residues persist long enough to potentially harm pollinators when they visit the crop.

- Applicators apply systemic insecticides to fruits and vegetables. These products move through the plant to flowers in quantities that could harm pollinators.

- Applicators apply insecticides outside the fruit or vegetable production field that move (in some manner) into the field in sufficient quantities to harm pollinators.

- The residues of systemic insecticides remain in the soil from a previous crop. The fruit or vegetable crop then takes up the insecticide, which moves to flowers in quantities large enough to harm pollinators.

Figure 3. A honey bee foraging sweet corn pollen.

Figure 4. A spray boom applies pesticide in sweet corn.

To minimize the potential damage to pollinators, consider these seven best management practices.

Read and Follow Insecticide Labels

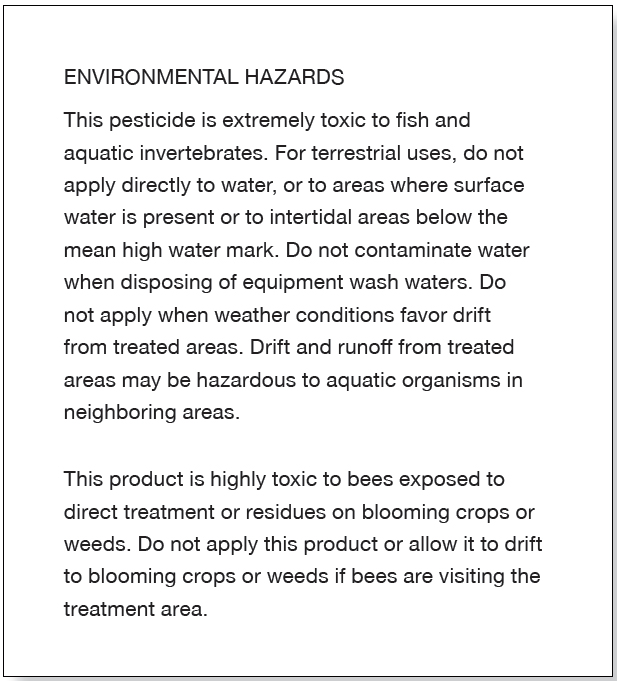

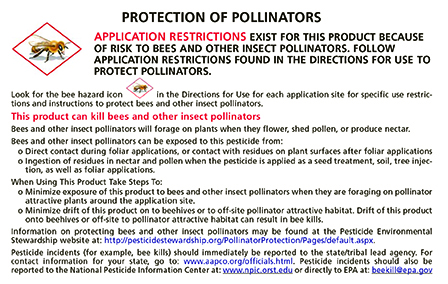

Insecticide labels contain specific instructions to help you reduce risks. The labels commonly require you to wear protective equipment and avoid bird baths, ponds, streams, and toys. All insecticides that are toxic to pollinators have warnings on the label. These warnings are often hard to find on some older insecticide labels (Figure 5). However, many newer insecticides have special bee icons on their labels that draw attention to the potential for harm to pollinators (Figure 6). They often have specific instructions for minimizing the risk.

Figure 5. This older pesticide label has a pollinator warning that is difficult to find.

Figure 6. This example of a newer pesticide label includes pollinator warnings that are easy to spot.

2. Follow IPM Principles

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is a system that combines different methods. Its aim is to keep pest populations low while allowing for profitable production and minimizing adverse environmental effects. To reduce the risk of harming pollinators, IPM principles guide producers to take advantage of noninsecticidal practices that can reduce pest damage. For example, you might rotate crops to control Colorado potato beetle or conserve predator mites to control European red mites.

When deciding whether to apply an insecticide, determine whether the net profit from applying the insecticide is greater than the cost of applying it. Making an informed decision usually involves scouting your field or orchard to determine the level of pests that are present. It doesn’t make good sense to spend $50 per acre to avoid $30 per acre in losses. Using IPM principles will often reduce the amount of insecticides you need to apply.

Figure 7. To follow IPM principles, scout fields or orchards to get a sense of the severity of the pest infestation.

3. Register with DriftWatch

The DriftWatch website (driftwatch.org) is a place where specialty crop producers and apiaries can register their production sites on a map. Pesticide applicators can access this data before applying anything to nearby fields. The rationale behind this site is to provide applicators with the locations of sensitive sites, so they can take precautions to avoid overspray or drift to locations where they are not wanted.

4. Don't Treat Areas Where Pollinators Visit

Some crops, like apples, have a very well-defined bloom period. For such crops, it is relatively simple to avoid spraying insecticides during bloom. All apple growers should avoid insecticide applications during the bloom period — roughly 10-14 days.

Other crops, like cantaloupe, bloom throughout the growing season. If melon growers stopped applying insecticides when the first flowers appeared, striped cucumber beetles would feed unabated and likely vector the bacterium that causes bacterial wilt of cucurbits to a large percentage of the plants in the field.

However, a cantaloupe flower only opens for one day and it closes in the late afternoon. This means pollinators are unlikely to be in fields after the flowers have closed. This knowledge provides melon growers an opportunity to spray their fields with an insecticide in the late evening without harming pollinators. However, growers still need to use a nonsystemic insecticide so that the residue will only be on the outside of the new flowers that open the next day. In that way pollinators will not contact the insecticide and no harm will ensue.

Growers should also remember that pollinators will be attracted to dandelions and other blooming weeds even if the crop is not in bloom. Applying insecticides when weeds are in bloom can also potentially harm pollinators.

5. Avoid Seeds Treated with Neonicotinoids

Some vegetable seeds are sold with a coating of a neonicotinoid insecticide, usually thiamethoxam. If you direct-seed a crop (such as pumpkins), the insecticide in the seed coating will control insects such as aphids and striped cucumber beetles for up to three weeks. However, because neonicotinoids are systemic insecticides, they move into the flowers and will be present in the pollen in levels that could harm pollinators.

If you grow transplants in a greenhouse for four or five weeks before planting them in the field, the insecticide from a coated seed will not control any insect pest in the field. But residues may be present in the pollen, which would harm pollinators.

Growers who are direct-seeding crops may decide that the insect control that treated seed provides outweighs the potential harm to pollinators based on field history. However, growers who are transplanting crops will receive no benefit from insecticide-treated seeds but still risk harming pollinators. If you are planning transplant production, request seeds with no insecticide treatment from your seed dealer.

Figure 8. Avoid applying insecticides when pollinators are actively foraging in the area (like this bumblebee on blackberry flower).

Figure 9. Cantaloupe flowers only open once and close in the late afternoon, so time pesticide applications to avoid harming polllinators, like this honey bee.

Figure 10. Bacterial wilt can devastate cantaloupe plantings if you do not control striped cucumber beetle, which carries the bacterial wilt pathogen.

Figure 11. Seed companies often apply pesticides as a coating on their seed, as with this sweet corn seed.

Figure 12. Choose your seed carefully to match your production practices. If you are transplanting your crop, then using a treated melon seed (like the seeds on theleft) will not control pests but could harm pollinators.

6. Use Low Rates for Neonicotinoid Soil Drenches

Some growers of cucurbits and other crops apply a neonicotinoid insecticide (Admire Pro® or Platinum®) at planting. Like the seed treatments, these applications provide about three weeks of insect control. Never use a soil drench insecticide if you also have seed treated with a neonicotinoid. The combination will not improve insect control.

Research has shown that soil drench applications at the low end of the label range provide control equal to applications at the highest label rates. However, the lower rates reduce (but don’t eliminate) residues in the pollen. Although both rates produce residue levels in the pollen that could cause harm, the lower rate is less likely to cause a problem.

7. Communicate with Your Bee Provider

If you rent bees to pollinate your crops, be sure to talk with your beekeeper about the pests that you have to deal with and the need for any insecticides you may apply. Coordinate the arrival and departure of the bees with your insecticide applications to ensure you minimize any potential harm to the bees.

Pollinators, both domesticated and feral, are important to the production of many fruits and vegetables. By following these few suggestions, fruit and vegetable growers can do their part to preserve the health of all of our pollinators, as well as maintain the goodwill of beekeepers.

Figure 13. A honey bee yard.

Find more publications in the Protecting Pollinators series by visiting the Purdue Extension Education Store edustore.purdue.edu

READ AND FOLLOW ALL LABEL INSTRUCTIONS. THIS INCLUDES DIRECTIONS FOR USE, PRECAUTIONARY STATEMENTS (HAZARDS TO HUMANS, DOMESTIC ANIMALS, AND ENDANGERED SPECIES), ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS, RATES OF APPLICATION, NUMBER OF APPLICATIONS, REENTRY INTERVALS, HARVEST RESTRICTIONS, STORAGE AND DISPOSAL, AND ANY SPECIFIC WARNINGS AND/OR PRECAUTIONS FOR SAFE HANDLING OF THE PESTICIDE.

June 2016

It is the policy of the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service that all persons have equal opportunity and access to its educational programs, services, activities, and facilities without regard to race, religion, color, sex, age, national origin or ancestry, marital status, parental status, sexual orientation, disability or status as a veteran. Purdue University is an Affirmative Action institution. This material may be available in alternative formats.

This work is supported in part by Extension Implementation Grant 2021-70006-35390 / IND90001518G-1027053 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

765-494-8491

www.extension.purdue.edu

Order or download materials from edustore.purdue.edu