Pest & Crop Newsletter, Entomology Extension, Purdue University

- Corn Rootworm Hatch Beginning in West Central Indiana

- Corn Earworm Moths Captured Extremely Early

- Slug Damage Reports Continue

- Black Light Trap Catch Report

- Wrapped and Twisted Whrols in Corn

- Some Ugly Ducklings Grow Up to be Ugly Ducks, Not Beautiful Swans

Corn Rootworm Hatch Beginning in West Central Indiana - (Christian Krupke, John Obermeyer, and Larry Bledsoe)

- Hatch of rootworm in WC Indiana occurred on or around May 29.

- Rootworm populations may take another “environmental” hit should heavy rains continue.

- Sampling for larvae and assessing insecticide performance will be possible in several weeks.

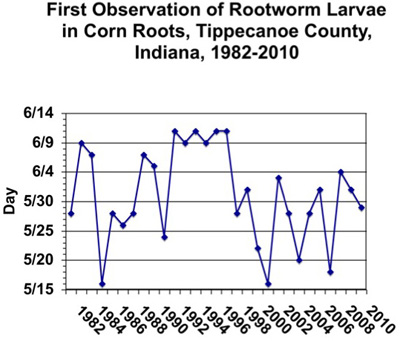

With several reports of firefly flashes in early May, we expected an early start to rootworm egg hatch in Tippecanoe County (see Pest&Crop #6, “Corn Rootworm Development: Fireflies and Bt Corn”). After searching hundreds of seedling roots from last year’s rootworm trap crop area throughout the month of May, the first larva was found on Tuesday June 1. Judging by its size, it probably emerged sometime over the Memorial Day weekend, likely Saturday the 29th.

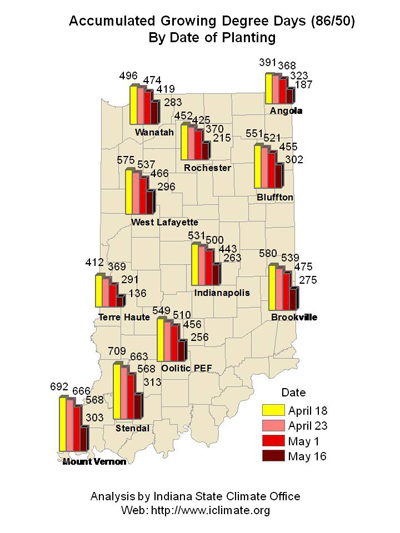

This date is just a benchmark and of little significance on its own. The key message here is that the rootworm egg hatch period is very prolonged (this is partially because eggs are laid at a variety of depths/temperatures), ensuring that whenever you plant, rootworms will be waiting for you. This year, the peak (highest activity) hatch will likely occur in mid-June. This underscores the fact that anyone still planting or replanting corn during the next two weeks should consider rootworm protection if they would typically do so.

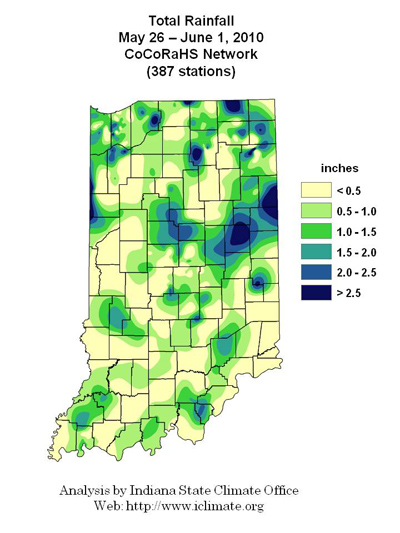

The biggest question is what potential risk for rootworm damage exists this year. As explained many times, rootworm eggs are very durable and generally over-winter quite well…no matter how cold. Newly-hatched larvae are the vulnerable stage in the biology of this pest. They are especially susceptible to drowning in wet soils. The springs of 2008 and 2009 were notoriously wet during the early weeks of June, when most larvae were hatching. With rains already moving through the state this year during the first week of June, rootworm may be set for another rough season. Obviously this story will be played out during the next several weeks. Please keep us informed of your observations.

Rootworms hatching from eggs, next to pinpoint

First instar larva feeding inside corn root

It is still too soon to sample for rootworms, as the hatching larvae are very small and hidden within the roots – not visible without a dissecting microscope. However, they grow quickly and by mid to late June, sampling will give an indication of the performance of the soil/seed insecticide or trait employed. This requires digging up and breaking the soil away from the roots of several plants in a field. Better yet, immerse the entire root ball in a 5-gallon bucket of clean water and shake it around. After 5-10 minutes, larvae will float to the surface and the cleaned root can be inspected for feeding damage. The larvae are relatively easy to identify and resemble the size and shape of a grain of rice: small (1/8 to 1/2 inch in length), slender, white larvae with brown head and tail sections. More on sampling will be in a future issue of the Pest&Crop.

![]()

Corn Earworm Moths Captured Extremely Early – (Christian Krupke and John Obermeyer)

On May 12 we caught our first corn earworm moth in a black light trap in Jennings County (SE Indiana). Two days later, a black light trap in Tippecanoe County picked up one moth. Immediately this gave the alert for sweet corn growers, with extremely early plantings, to begin their pheromone trapping. It is suspected that these moths rode one of many storm-fronts from the Gulf States. After a quiet period for catches, the pheromone traps have begun to catch significant numbers of moths over the Memorial Day weekend. Consider this an alert to producers with high-value corn close to tasseling. It is possible that earworm damage will be seen in the whorls of yellow dent corn, often mistaken for fall armyworm feeding. Though this damage may look severe, it is often in small patches of the field and the corn should grow out of it.

![]()

Slug Damage Reports Continue – (Christian Krupke and John Obermeyer)

Corn and soybean fields with significant residue cover are candidates for slug damage this year. The relentless rain showers that continue to move through the state have created a perfect environment for developing juvenile slugs as they feed on the crops. As mentioned in the last two Pest&Crop newsletters, via article and video, the best control is sunshine and warmth. In other words, conditions for the crop to be able to outgrow slug feeding.

In desperation to save the crop, some have considered home remedies. Applications of liquid and/or granular insecticides have proven to work poorly when used for slugs, largely due to the fact that slugs are not insects and therefore are not readily controlled by insecticides. Salt in high concentrations will kill slugs. Armed with this knowledge, producers that have attempted to spray liquid fertilizers at night, leaving crispy corn and sleep deprivation to report for their efforts. It doesn’t work – concentrations of fertilizer that are high enough to kill slugs will likely harm the crop, defeating the whole purpose.

In areas of fields that need replanting, disturbing the soil and residue with light tillage will work wonders, exposing the slugs to light and heat and making the field less hospitable. This is dependent upon soils being in good condition for tillage. Planting into wet soils will only exacerbate the situation, as slugs will gladly feed in the open seed-slots, once again destroying the seedlings. Although it is frustrating, the best thing to do is be patient and hope for sunlight and heat.

Seedling corn "slimed" to the ground

![]()

Click here to view the Black Light Trap Catch Report

Update on Fungicides for Soybean Rust Management – (Kiersten Wise)

Active soybean rust infections have not yet been detected in the southern United States on kudzu or soybean. Soybean rust survives through the winter on kudzu, and freezing temperatures this winter and early spring killed back most of the kudzu in the south. Therefore the amount of overwintering soybean rust spores available to infect kudzu and soybean were greatly reduced. Although soybean rust has not yet been confirmed in the U.S., scouting efforts continue in southern states and it is likely that the disease will be detected in the coming weeks.

The fungicide Topguard (Fultriafol; Cheminova) has received an EPA Section 3 label for use on soybean in 2010, and should be available for use in Indiana later in the month. This means that a Section 18 Emergency Exemption EPA label is no longer needed to apply this fungicide for soybean rust management in Indiana. For an updated list of fungicides labeled for use on soybean rust, please reference the following site: <http://www.ppdl.purdue.edu/PPDL/pubs/fungicide_table.pdf>.

Indiana will once again participate in the national sentinel plot system, and will monitor 11 fields on a weekly basis for soybean diseases, including rust, beginning in June. Support for the monitoring program is provided by the Indiana Soybean Alliance. Weekly updates on soybean growth stages, crop condition, and disease observations will be posted online at the ipmPIPE web site <http://www.sbrusa.net> by clicking on the state of Indiana on the national map. Producers are also able to track the movement of soybean rust at this website.

Indiana soybean producers can also subscribe to the Indiana soybean disease update list serve, at https://lists.purdue.edu/mailman/listinfo/indiana-soybean-update. This email alert service will provide convenient and timely updates on soybean disease monitoring in Indiana, and also provide information on fungicide spray applications if soybean rust reaches Indiana at a critical time during the growing season. Purdue University will continue to maintain a toll-free soybean disease hotline, which is updated weekly beginning in late June. The phone number is 866-458-RUST (7878). We will also provide updated commentary in the Pest&Crop newsletter as the season develops.

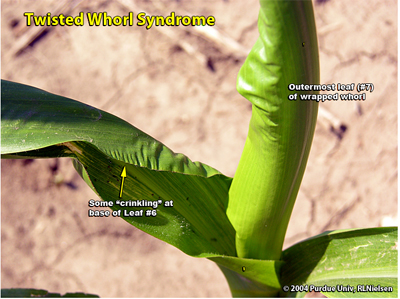

Wrapped and Twisted Whorls in Corn – (Bob Nielsen)

The curious phenomenon often referred to as the “twisted whorl syndrome” often occurs when young corn shifts quickly from weeks of slow development (cool, cloudy weather) to rapid development (warm, sunny weather). The occurrence of the twisted whorl syndrome is not uncommon, but rarely affects a large number of fields in any given year or a large percentage of plants within a field.

Twisted whorl syndrome (V6 plant)

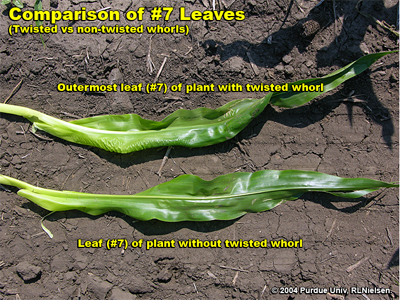

The typical growth stage when growers notice the twisted whorls is late V5 to early V6 (five to six visible leaf collars, approximately knee-high). The lowermost leaves are typically normal in appearance, although some may exhibit some crinkled (accordion-like) tissue near the base of the leaf blade. Beginning with the sixth or seventh leaf, the whorl is tightly wrapped and often bent over at right angles to the ground.

Sometimes you can spot the early onset of this phenomenon one or two leaf stages prior to the dramatic appearance of the phenomenon. The early stages of twisted whorl are not dramatic to the casual observer, but will catch the eye of the seasoned crop scout.

Early stage of twisted whorl syndrome

I will freely admit that we do not fully understand why this symptom develops. For some reason, the leaves of the whorl of affected plants do not unfurl properly, as if the rolled leaf tissue has lost its elasticity or has become “sticky”. Younger leaves developing deeper in the whorl are unable to emerge through the tightly wrapped upper leaves. The subsequently tightly twisted whorl then bends and kinks from the pressure exerted from the younger leaves’ continued growth.

One’s natural instincts would blame the twisted growth on herbicide injury. Indeed, where cell growth inhibitor or growth regulator herbicides are applied pre-plant or pre-emergence, shoot uptake of the herbicide by the emerging seedlings can indeed cause twisted growth of the young plants. Late application of growth regulators can also cause twisted whorls in older plants when leaves and whorl intercept a substantial amount of the herbicide. Widespread occurrence of the twisted whorl syndrome is not, however, usually accompanied by the common thread of any particular herbicide application.

Some have questioned whether wind damage can give rise to this phenomenon by somehow damaging the young inner whorl leaves. I’ve not often tracked the occurrence of strong winds with the development of the twisted whorl symptom, but it’s no secret that there were a number of strong storm and wind events throughout the state over the past couple of weeks.

"Normal" V4 plant

In other situations over the years, this phenomenon has often been associated with a sharp transition from periods of slow corn development (typically, cool cloudy weather) to periods of rapid corn development (typically, warm sunny weather plus ample moisture). Some have argued that it is the reverse, transitioning from rapid periods of development to slow. Or…….maybe it is a transition from rapid development to slow and back to rapid that triggers the symptoms.

Whatever the cause, the appearance of the twisted whorl plants is indeed unsettling and one could easily imagine that the twisted whorls might never unfurl properly. Given another week, though, twisted whorls of most of the plants will unfurl and affected plants subsequently develop normally. It is not uncommon to see hybrids vary in the frequency of twisted whorls.

If you didn’t notice the twisted whorls to begin with, you may notice the appearance of “yellow tops” across the field after the whorls unfurl. The younger leaves that had been trapped inside the twisted upper leaves emerge fairly yellow due to the fact that they had been shaded for quite some time. In addition to being fairly yellow, the leaves will exhibit a crinkly surface caused by their restricted expansion inside the twisted whorl. Another day or two will green these up and the problem will no longer be visible.

The Good News: Yield effects from periods of twisted growth caused by weather-related causes are minimal, if any. By the time the affected plants reach waist to chest-high, the only evidence that remains of the previous twisted whorls is the crinkled appearance of the most-affected leaves.

Twisted whorl syndrome

Twisted whorl syndrome

Twisted whorl syndrome

Comparison of #7 Leaves

Twisted whorl syndrome

"Yellow top" symptom shortly after twisted whorl finally unwraps

![]()

Some Ugly Ducklings Grow Up to be Ugly Ducks, Not Beautiful Swan – (Bob Nielsen)

Some of the regulars uptown at the Chat ‘n Chew Cafe have been griping about the article I wrote several weeks back that suggested that young corn that was looking ugly at the time would come out of it once it reached the V6 stage of development (Nielsen, 2010). It seems that everybody and his brother are still looking out their kitchen windows at fields of corn that remain stunted, yellow-green, and otherwise very uneven in their appearance. Everyone (farmers, their wives, their fathers, their landlords, their bankers) is wondering what on earth is going on with some of these fields and why these ugly ducklings are not turning into the beautiful swans that my aforementioned article suggested would happen.

In all fairness, I did say in that article that “if the plants hang in there until they reach the five- to six-leaf stage”, then they would likely “turn the corner” and look much better. You have to admit that, indeed, there are quite a few fields that have done just that and look great today versus several weeks ago.

Unfortunately, quite a few other fields continue to look ugly even though they are approaching V5 and beyond. The question on everyone’s mind is “Why have these fields deteriorated instead of improving?” Furthermore, sometimes ugly fields are across the road from beautiful fields. What’s up with that?

There is no single answer that explains why there continue to be so many “ugly duckling” fields around the state at the moment. Instead, there are multiple possibilities occurring in all possible combinations from field to field. The degree of “ugliness” is very much dependent on the timing and duration of the particular causes of the problem for any given field.

Here is a short “laundry list” of the stressors contributing to the problems early in this growing season. Mix and match them to help diagnose the combination of factors for the field(s) of your choice. Many of these stressors can be more significant in continuous corn cropping systems, especially if minimal or zero tillage were used. The negative effect of many of these stressors will be greater the younger the crop was when they occurred. Hybrids naturally differ for tolerance to these stressors, which adds to the confusion when comparing one field to another.

Finally, remember that stressed plants that have not had time to recover do not tolerate subsequent stress as well as healthy plants. Consequently, healthy fields “turn the corner” and become beautiful swans and severely stressed field “stall out” and remain ugly ducks.

Corn Crop Stressors Thus Far in 2010

- Frequent and / or heavy rain events that kept surface soils saturated for lengthy periods of time.

- Leaching of mobile nutrients, like nitrogen, below the root depth of the young corn plants.

- Several weeks of cool and cloudy weather that certainly was not optimum for photosynthesis.

- Herbicide injury due to slow corn plant metabolism during cool, cloudy weather.

- Above-ground frost damage; especially if multiple occurrences.

- Above-ground damage to blowing sand / soil particles; aka “sand blasting”; especially if multiple occurrences.

- Damage to kernels or seedlings from a number of pests including wireworms, slugs, nematodes, seedling blight, and anthracnose.

- Nitrogen tieup by soil microbes responsible for decomposing residues near the surface; especially corn following corn.

- Soil compaction from last fall’s late, wet harvest; aggravates the saturated soil problem.

- Soil compaction from tillage and planting operations this spring; aggravates the saturated soil problem.

- Natural spatial variability within fields for soil drainage characteristics.

- Natural spatial variability within fields for soil color; affects early soil temperatures and seedling development.

- Tile drainage systems that are non-existent, inadequate or poorly functioning.

- Excessively low soil pH; affects early root development.

- No starter fertilizer or inadequate starter fertilizer rates; not desirable in a year like this.

Related References

Faghihi, Jamal, Betsy Bower, Christian Krupke, and Virginia Ferris. 2010. Corn Nematodes. Purdue Pest & Crop Newsletter, Purdue Univ. [online]. <http://extension.entm.purdue.edu/pestcrop/2010/issue4/index.html#nematode> [URL accessed June 2010].

Nielsen, RL (Bob). 2007. Mitigate the Downside Risks of Corn Following Corn. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. [online] <http://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/corn/news/timeless/CornCorn.html> [URL accessed June 2010].

Nielsen, RL (Bob). 2008. A Recipe for Crappy Stands of Corn. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. [online] <http://www.kingcorn.org/news/articles.08/CrappyRecipe-0422.html> [URL accessed June 2010].

Nielsen, RL (Bob). 2010. Corn and the Ugly Duckling. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. [online] <http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/UglyDuckling.html> [URL accessed June 2010].

Krupke, Christian & John Obermeyer. 2010. Are Slugs Sliming Your Crop? Purdue Pest & Crop Newsletter, Purdue Univ. [online] <http://extension.entm.purdue.edu/pestcrop/2010/issue8/index.html> [URL accessed June 2010].

Sweets, Laura. 2010. Anthracnose in Corn. Integrated Pest & Crop Management Newsletter, Univ of Missouri [online] <http://ppp.missouri.edu/newsletters/ipcm/archives/fullissue/v20n10.pdf>[URL accessed June 2010].

Wise, Kiersten. 2010. Wet Soils Favor Seedling Blights in Corn and Soybean. Purdue Pest & Crop Newsletter, Purdue Univ. [online] <http://extension.entm.purdue.edu/pestcrop/2010/issue8/index.html#wet> [URL accessed June 2010].