Providing sufficient but not excessive nitrogen (N) to corn is difficult especially with fall and early spring fertilizer applications where N loss can vary substantially with the timing of the application relative to the occurrence of warm soil and excessive rainfall. Nitrogen deficiency occurs most growing seasons and often leads to an interest in applying N fertilizer beyond the growth stage and height where standard N application equipment can be used.

Nitrogen applied up to 2-3 weeks after silking to N deficient but otherwise healthy corn can result in increased grain yield. The greater the N deficiency and the earlier the N application the larger the yield increase. An irrigated 2-year study conducted in Nebraska illustrates this point well. (We gratefully acknowledge the support provided for research conducted by Dan Emmert and Eric Miller by the Indiana Corn Marketing Council, Pioneer Hi-Bred Int’l, A&L Great Lakes Labs (discounted analysis costs), Purdue Univ. Office of Ag Research Programs, and all of the Purdue Ag Center staff.)

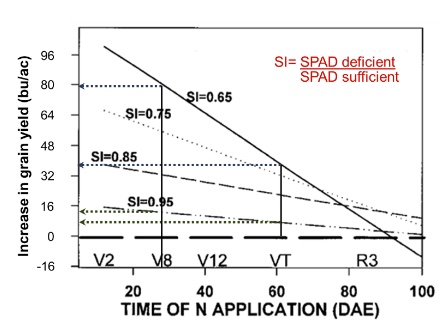

Rates of N were applied from 0 to 300 lb N/ac at planting to establish different levels of N sufficiency. Nitrogen sufficiency (SI) was quantified with a SPAD chlorophyll meter by measuring greenness of the most recently collared leaf in sub-optimal N rates compared to the highest N rate (SI=1 indicates no N deficiency).

At V8 the application of N to corn with an SI=0.95 (slight N deficiency) increased yield about 14 bushels per acre (bu/ac. With greater N deficiency (SI=0.65) the yield increase was nearly 80 bu/ac (see figure to right).

Nitrogen applications later in the season were not able to produce as great a yield increase as those obtained at V8. Nitrogen applied at tasseling (VT) to corn with an SI=0.65 increased yield less than 40 bu/ac. At an SI=0.95 at VT the increase in yield with N application was about 8 bu/ac.

Irrigation provides a means to apply N, move it into the rootzone, and keep the rootzone moist; optimizing N uptake and grain yield response to late- season N. Limited rainfall in non-irrigated fields may hinder response to late-season N application.

Research in Indiana under rainfed conditions can be used to illustrate this point (Dan Emmert -M.S. thesis, 2009)2. Grain yield was increased 27 and 40 bushels per acre at two locations in west-central Indiana by a V13 N application of 175 lb/ac. Little rainfall occurring in the first 2 to 3 weeks after application and total rainfall after the N application was 10 an 15 inches, respectively for the two locations. Yield with the late-season N application was 114 and 139 bu/ac reflecting less than ideal conditions throughout the season.

With more timely and greater rainfall (0.3” of rainfall one and two weeks after the late-season N application and total of 20 inches after application), a yield increase of 64 bu/ac and a maximum yield of 184 bu/acre was realized in a study conducted in northwest Indiana.

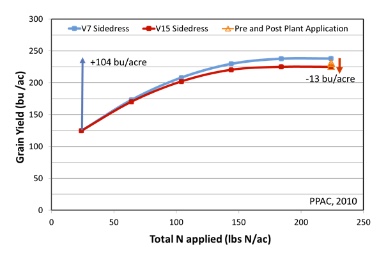

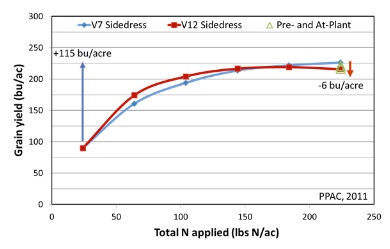

With better growing conditions at this same location in 2010 and 2011 an additional 100 bu/ac were made by applying high rates of N at V15 and V12 to N deficient corn (see below–Eric Miller – M.S. thesis, 2012). Optimum yield ranged from 215 to 240 bu/ac.

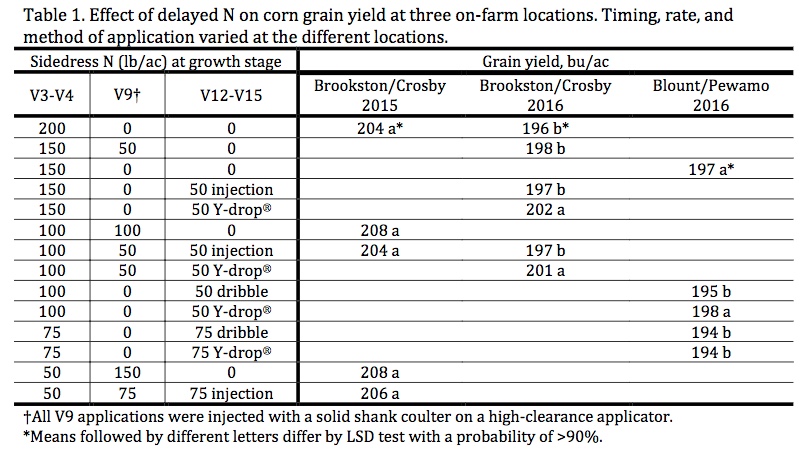

The previous mentioned trials had little N applied early in the season so N deficiency was relatively strong and the yield response to applied N was large. Smaller responses should be expected with less severe N deficiency. Three on-farm trials with 50 to 150 lb N/ac delayed to V9 or beyond showed little to no yield benefit of holding back some of the N because N deficiency was minimal (Table 1).

Several effective methods can be utilized to apply N to tall corn. A solid shank applicator (pictured left) that injects N into a coulter slit a couple of inches deep into the soil prevents ammonia (NH3) volatilization from liquid urea-ammonium nitrate. Alternatively the same high-clearance applicator can be fitted with drop tubes or Y-Drops® to place the liquid N in a narrow band on the soil surface. Although NH3 volatilization may occur when liquid N is left on the soil surface the magnitude of loss is likely less than 5% of the N applied when banded in full canopy corn.

A solid shank applicator.

A high-clearance box spreader.

Granular urea can also be spread by airplane or high-clearance box spreader (pictured right). Fifteen to 30% of the N applied in broadcast urea may be lost to NH3 volatilization. Compensating for potential N loss by applying a higher N rate or by using a urease inhibitor to reduce NH3 loss (NBPT or NPPT) should be considered.

Differences among application methods in crop damage, speed of application, and other practical factors should also be considered when choosing among methods of application.

Irrigated corn provides the easiest opportunity to apply N to corn. Fertigating with liquid urea-ammonium nitrate is an efficient cost-effective way to provide late-season N to corn. Often 20 to 30 lb N/ac are applied per N application, but as much as 50 lb N/ac can be applied with sufficient dilution to avoid foliar burn. Adding N to irrigation water increases the importance of irrigation system application uniformity as water and N both have substantial impact on crop growth and yield. Since irrigation maintains high soil moisture, leaching and/or denitrification of N may occur with excessive irrigation or rainfall. Thus multiple small rates of N application are helpful in reducing N loss. Additional guidelines for fertigation can be found in Irrigation Fact Sheet #12.4

Summary

Corn has tremendous capacity to respond to late-season N application provided the plant is N deficient, but otherwise healthy. The earlier the application the better but profitable responses have been obtained as late as 2 to 3 weeks after tasseling. In non-irrigated systems there are advantages and disadvantages to each application method and source with no clear winners or losers. Injecting urea-ammonium nitrate into irrigation water is the most convenient application method when irrigation is available.

References

1Maize Response to Time of Nitrogen Application as Affected by Level of Nitrogen Deficiency. 2000. D.L. Binder, D.H. Sander, and D.T. Walters. Agron. J. 92:1228–1236.

2Using Canopy Reflectance to Monitor Corn Response to Nitrogen and the Effects of Delayed Nitrogen Application. M.S. Thesis, Purdue Univ., May 2009.

3Nitrogen Application Timing and Rate Effects on Nitrogen Utilization of Corn and the Adoption of Active Optical Reflectance Sensors for Nitrogen Management. M.S. Thesis, Purdue Univ., May 2012.

4IIrrigation Fact Sheet #12 – Nitrogen Application with Irrigation. Lyndon Kelley. http://msue.anr.msu.edu/uploads/236/43605/FactSheets/12_NitrogenApplicationnWithIrrigationFact_Sheet.pdf.