Typical El Niño Winter Pattern

Highlights for the Great Lakes

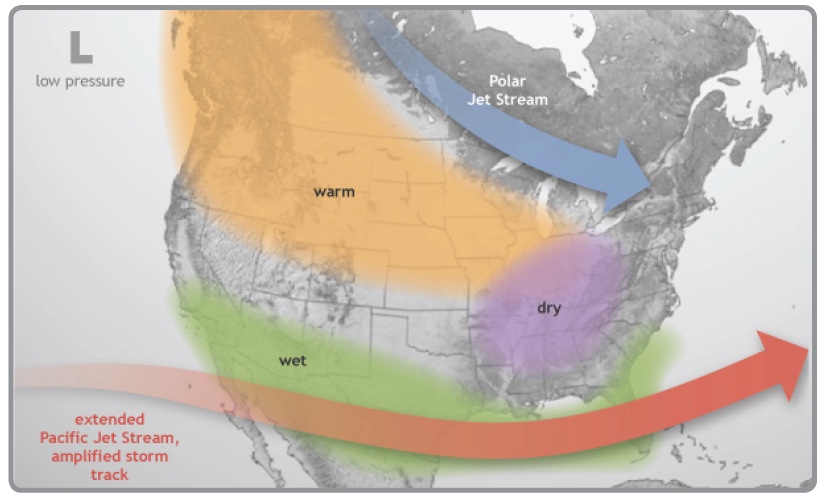

An El Niño develops when sea surface temperatures are warmer than average in the equatorial Pacific for an extended time. This is important to North America because El Niño can impact our weather patterns, especially in the winter. Although each El Niño is different, there are some general patterns that are predictable. For instance, the polar jet stream is typically farther north than usual, while the Pacific jet stream remains across the southern U.S. This pattern brings above-normal temperatures to much of the Great Lakes region, particularly across the north. This does not mean cold weather will not happen this winter, but extreme cold weather events may be milder and less frequent.

The image above shows the typical pattern in the winter during El Niño events. The polar jet stream tends to stay to the north of the Great Lakes region, while the Pacific jet stream remains across the southern U.S. With the Great Lakes positioned between the storm tracks, warmer and possibly drier conditions can develop during El Niño events. (Image courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.)

El Niño Outlook

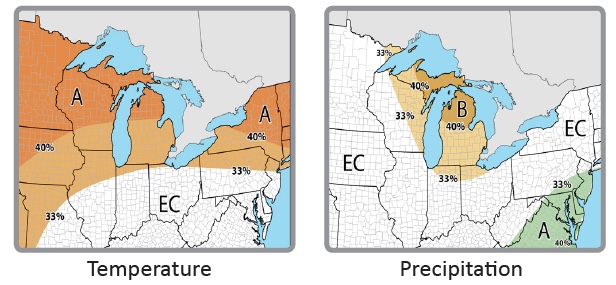

As of October, the winter outlooks for the region show that below-normal precipitation is favored for the central and western portions of the basin. This can result in reduced snowpack that could impact spring runoff and may have negative implications for many sectors. The temperature outlook indicates that the basin could have above-normal temperatures, especially further north. Warmer temperatures could have positive implications, such as reduced heating costs, fewer transportation costs and delays, and increased retail sales. Negative implications from warmer temperatures include reduced winter recreation and increased survival through the winter of agricultural pests.

Winter temperature and precipitation outlooks valid for Dec. 2018 – Feb. 2019 (EC: Equal chances of above, near, or below normal; A: Above normal; B: Below normal)

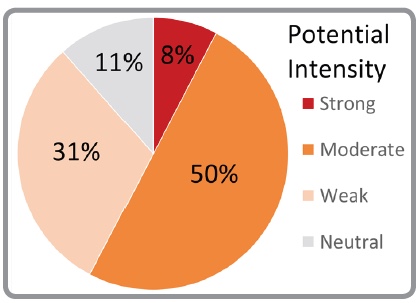

According to the Climate Prediction Center, ENSO-neutral conditions are present. Outlooks favor the development of a weak to moderate El Niño event in the next few months, which could continue through the winter (70-75% chance). An El Niño Watch is in effect. The chart below shows the potential intensity of this winter’s El Niño, with data from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society.

El Niño strength, winter 2018-19

Potential Winter and Spring Impacts

For the Great Lakes, most of the winter impacts are beneficial. Milder winter weather could benefit winter wheat, forage crops, cover crops, and fruits. However, because an El Niño winter typically results in reduced snowpack, this could expose these crops to occasional cold air outbreaks and harsh wind. Milder winter temperatures should be beneficial for livestock producers by reducing operating costs and stress to animals while improving production.

Mild and dry winters with decreased snowfall can have a significant overall positive impact on the economy. The largest positive impacts are reductions in heating costs and increased retail sales. Economic losses are suffered by those sectors that depend on normal winter weather, such as winter recreation, snow removal businesses, towing companies, and road salt sales. In addition, less ice on the Great Lakes could potentially lead to an extended navigation season for shipping.

Above-average temperatures could lead to reduced snowpack accumulation this winter season and a chance for decreased runoff into the lakes during the spring since runoff is typically a major contributor to increasing water levels. Since the lakes are mostly above average levels right now, this could lead to a return to normal water level conditions in the spring. Warmer winter temperatures may also contribute to reduced ice cover on the Great Lakes.

Comparisons and Limitations

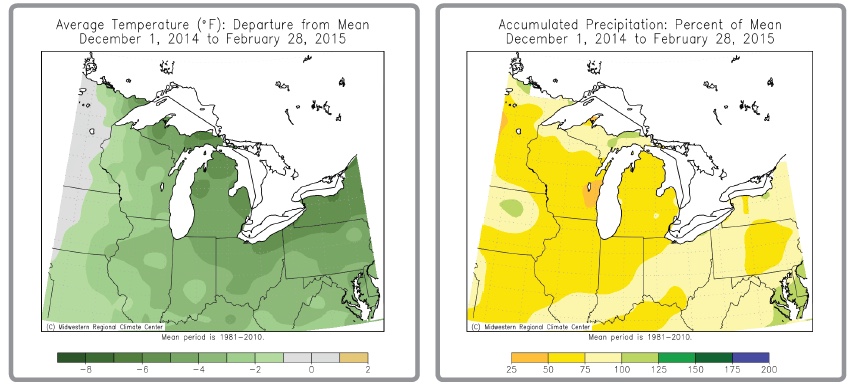

The maps below illustrate the winter conditions of the most recent weak El Niño event that occurred in the winter of 2014-2015. The Great Lakes region was cooler than average and precipitation was near or below average, especially around Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. Each El Niño is different and other factors should be considered, such as antecedent conditions or the Arctic Oscillation, which trumped the El Niño during winter of 2009-2010. While past El Niño events can help inform forecasters about certain conditions, there are some limitations. For instance, El Niño is not known to impact the track or intensity of any single weather system or the timing of freeze events in the fall or spring.

Maps courtesy of the Midwestern Regional Climate Center

Great Lakes Partners

Midwestern Regional Climate Center

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

NOAA NCEI

Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory

NOAA NWS Climate Prediction Center

NOAA Great Lakes Sea Grant Network

North Central River Forecast Center

Ohio River Forecast Center

Great Lakes Integrated Sciences & Assessments

American Association of State Climatologists

National Integrated Drought Information System

USDA Midwest Climate Hub

Author: NOAA’s Regional Climate Services Program