A planned fencing system is critical to an effective pasture system. The following article prepared by Jason Tower, Superintendent of the Southern Indiana Purdue Agricultural Center, is from the 2023 Heart of America Grazing Conference Proceedings. The article is used with permission from Jason Tower. Jason was a guest speaker about fencing and water systems to 51 students that are enrolled in the Purdue University Forage Management class on April 3.

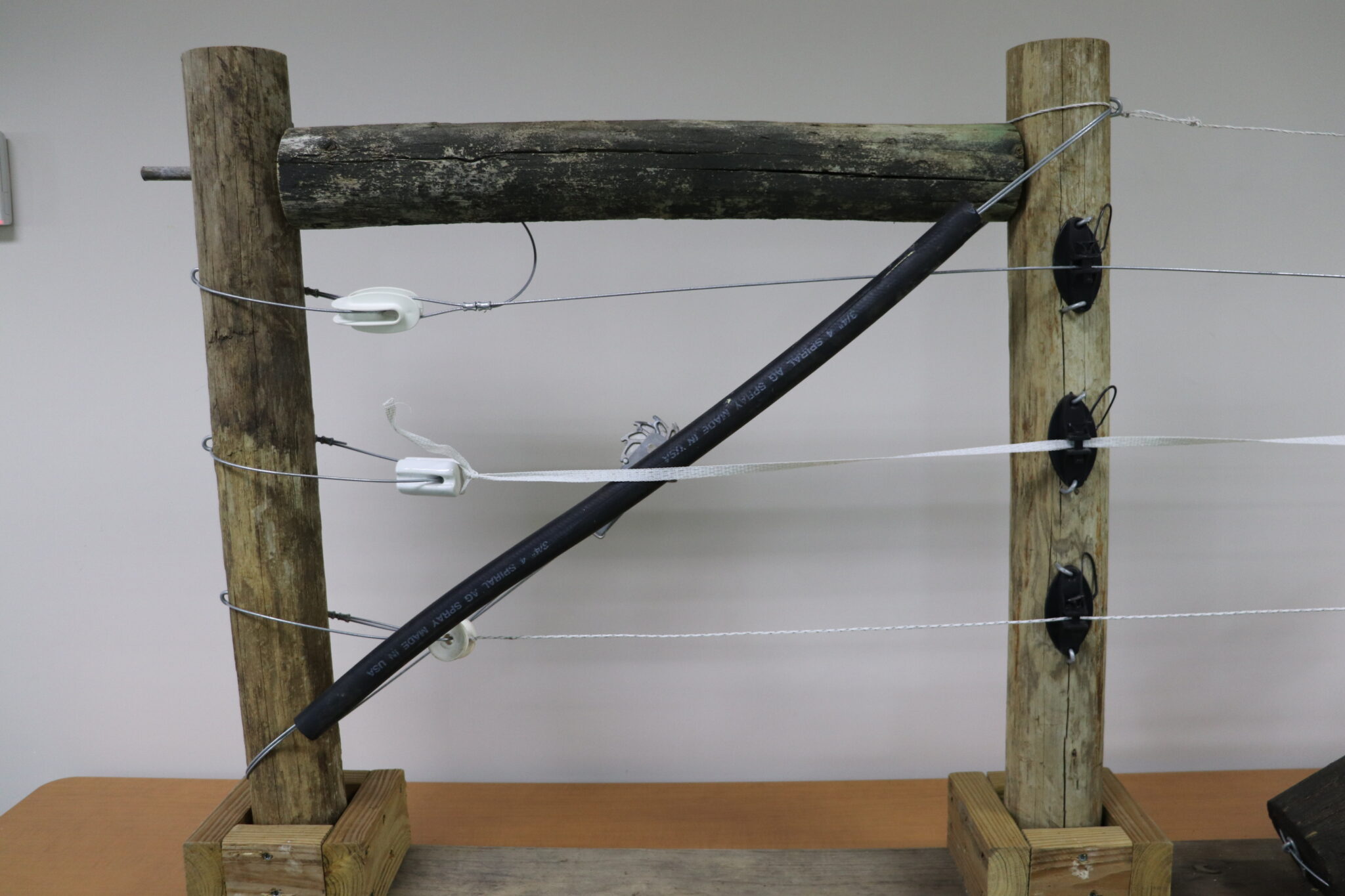

The fencing exhibit is one of a kind that was developed by Jason Tower for use when showing various electric fencing options. The display is part of his fencing presentation. (Photo Credit: Keith Johnson)

Jason Tower discusses different water float options with the Purdue University forage management class. (Photo Credit: Keith Johnson)

Evaluating need and resources are important steps in any project and developing a fencing system for livestock is no different. Each operation is going to have special requirements for fence depending on the topography of the land, the species and class of livestock in the operation, and the goals and intensity of the grazing program. Depending on how one evaluates the needs, this will determine the fencing system required. In the information that follows, there will be a series of thoughts and points of discussion to aid in the planning process. At the end of the article is a listing of online resources for greater detail on many of the points discussed.

If the fence is on a property line it might be considered a “partition fence” and would be required to be built to the standards specified in the state fence law. Each state might be different in this regard and state statute should be investigated. The state fence law can also specify which party is required to build which section of fence.

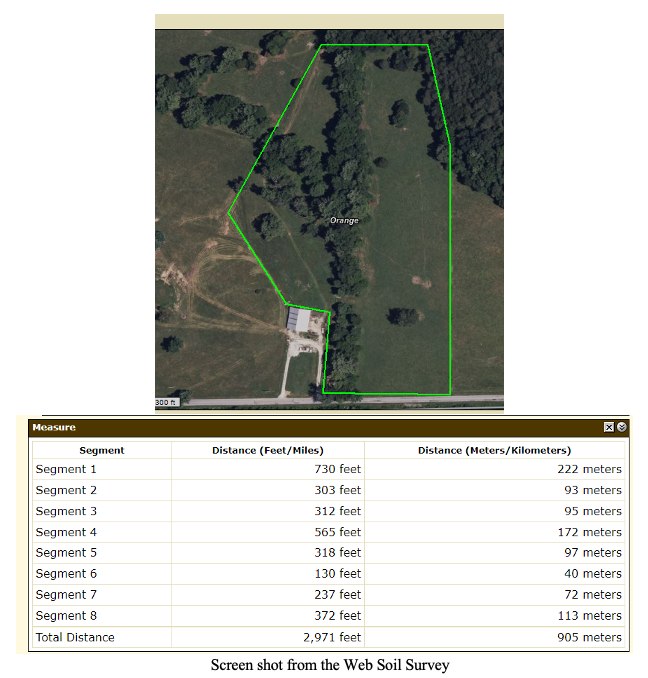

Once it is determined the type of fence that is required, either property line fence or interior fence, the planning process can begin. Technology exists to get good overhead views of the land to help determine locations of the fence. This technology might be an unmanned arial vehicle (UAV) with a camera or an online resource utilizing satellite imagery. With these photographic results downloaded onto a computer, it is now possible to get measurements for length of fence, estimate the locations and quantity needed for corner brace systems, and the exact locations of the fence based on property lines, shade locations, gate locations, and water locations among other factors. A producer can then take these maps to the pasture and physically look at and walk the areas to be fenced to ensure it makes sense on the ground. What made sense in the photo might not in person. As the manger thinks about the flow of livestock or sees a physical characteristic of the land that would change where a fence should be located, those adjustments can then be noted on the planning map before the building process is initiated.

Building fence to maintain livestock on the property, or off the property depending on the situation, would be determined by livestock species and class within the species. Fencing requirements for cow-calf pairs is much less substantial than would be required for does and their kids. For example, a 2-or-3-wire properly spaced electrified hi-tensile wire would be adequate for the cattle operation but for the goat operation, more than likely, this fence would not contain the animals. It would need to be 6 or 8 properly spaced electrified hi-tensile wires, or even a woven wire fence.

In planning a fencing system, maintaining flexibility in the interior fence should be a high priority. If a producer is involved in a cost share program (NRCS program EQIP) there might be requirements that interior fence be a permanent installation and be built to the required specifications. If the land is new to the operator and they have not managed livestock there before, it makes sense to be flexible and temporary with the interior fence. It takes a few grazing seasons to get a feel for the land and how livestock use different areas or how they might need to flow to get to handling facilities or watering locations. One can waste a great deal of time and effort building interior fence to only find out much of it was placed in the wrong location.

A grazier also needs to think about what type of agriculture equipment might be utilized in the operation. Will large fertilizer and spray rigs be used? Will hay production occur on some paddocks? Might multiple species of livestock be grazed? In answering these questions, location and gate size can be determined. How small permanent interior pasture divisions are made could also be a factor in deciding the fence type needed.

If electric fence is desired, is there a 120-volt power source on the property or will a solar powered system be required? Both systems can be designed to match the needs of the livestock and the length of fence. The longer the length of fence the more joule output is needed from the energizer. Also grazing small ruminant livestock will take a higher output energizer than cattle as greater voltage is needed to keep them in the proper location. Once the size and location of the energizer is determined, installing a proper grounding system is critical to the success of the system. If the electric fence system is not adequately grounded, the animals will not receive a shock strong enough to deter them from, crossing the fence regardless of the amount of voltage on the fence. Follow the manufacturer’s recommendation for ground rod installation and then test the system to be sure it meets the requirements Remember, an electric fence system is a psychological barrier, not a physical barrier to the animals. The animal’s initial interaction with the fence needs to be a memorable one.

Having electric fence available on the entire property greatly increases the flexibility of the types and locations of temporary fence that can be utilized. With electric fencing, producers have the ability to use step-in posts and poly wire (or electrified poly netting) to control the grazing movement of the livestock. This type of fence is very economical to purchase and is very time efficient to move on a regular basis to keep animals grazing a high quality and quantity diet and allows for proper recovery of the forages prior to the next grazing event.

Answering the question of “What type of fence do I need?” is not simple or short. Each farm and situation are unique and will require a tailored fence system. Taking time to think about and plan what the grazing system might be will aid greatly in getting the proper fence installed on the first attempt.