Pest & Crop Newsletter, Entomology Extension, Purdue University

Critical Time for Black Cutworm Scouting – (John Obermeyer)

• Temperatures now favor corn and cutworm development.

• Corn cutting is likely as larvae get over ½” in length.

• Higher-risk fields for damage are those where weeds existed in March.

Warmer temperatures, accompanied with rainfall, has recently planted corn “jumping” out of the ground and emerged corn turning green. This acceleration in warmth will also speed the development of black cutworm larvae. Amazingly, moths continue to be captured in large doses, see the “Black Cutworm Adult Pheromone Trap Report,” to further pile on the record catches received since March 23.

If your field looked like this weeks ago, you should be scouting it for cutworm today

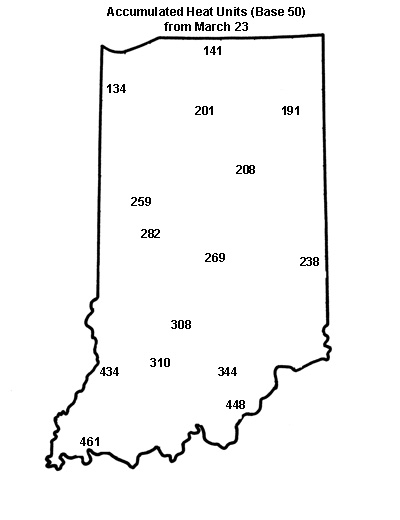

Refer to the accompanying map of accumulated heat units (base 50°F) from March 23. To date, according to the black cutworm developmental model, larvae are large enough throughout southern Indiana to be cutting corn. With the forecasted warm temperatures, this will soon be true throughout the central counties. These next couple weeks will be the critical time for cutworm scouting, especially in high-risk fields.

Accumulated heat units

Scout by inspecting 20 consecutive plants in each of 5 areas of a field (100 plants) for cutworms and feeding activity. Be sure to check areas that had an accumulation of weedy growth before or at the time of planting. Count and record the number of plants cut or damaged and determine the percentage of plants affected. Also collect black cutworm larvae (usually found near the damage, just beneath the surface during the day) and determine the average instar stage. A foliar, rescue insecticide may be necessary if 3% or more of the plants are damaged and black cutworm’s average larval instar is from 4 to 6. An instar guide is available inside the front cover of the Corn and Soybean Field Guide (a.k.a., pocket guide). Happy Scouting!

![]()

Asiatic Garden Beetle Grub Is Back – (John Obermeyer)

A call from Brian Warren, Frick Services of Whitley County, this past week alerted us to the fact that Asiatic garden beetle grubs are making their presence felt in sandy areas of fields in north central and northeastern counties. Notably, he was only finding damage in corn following soybean. Seed applied insecticides weren’t preventing the grubs from feeding on corn roots, more importantly the mesocotyl. Unfortunately there is no rescue treatment available. Damaged plants, if growing points aren’t compromised, may recover somewhat if grubs soon pupate (i.e., stop feeding) and ample moisture is available. Don’t let the size of the small grubs fool you, as Brian indicated, “they are like grubs on steroids.”

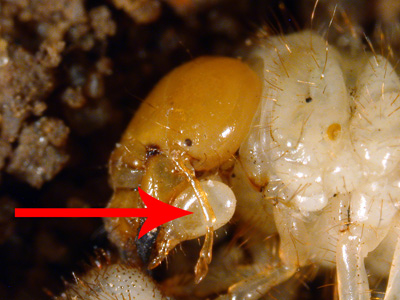

Japanese beetle and Asiatic garden beetle grubs compared

This "pouch" near the Asiatic garden beetle's mandibles are very distinctive of this species

![]()

Click here for the Black Cutworm Adult Pheromone Trap Report

![]()

Click here for the Blacklight Trap Catch Report

![]()

Be On The Lookout For A New Wheat Disease - (Kiersten Wise) -

Last week the University of Kentucky released an article documenting the discovery of a new disease of wheat in the United States called wheat blast. The article can be accessed at this link: <http://news.ca.uky.edu/article/uk-researchers-find-important-new-disease>. Wheat blast is caused by the fungus Magnaporthe oryzae (Pyricularia grisea), and has caused moderate to severe yield loss in wheat in Brazil since its detection in the mid 1980s.

Wheat blast was confirmed in Kentucky in 2011, and was limited to a single occurrence of the disease in one research plot in Princeton. No disease was confirmed in any commercial field in Kentucky in 2011. We have not confirmed the disease in Indiana to date, but this is a key time to scout for wheat blast. Symptoms of wheat blast are very similar to those of Fusarium head blight (FHB), and farmers and consultants should look for bleached heads at head emergence and early flowering. Wheat blast symptoms typically appear BEFORE symptoms of FHB, and heads will not have the orange or pink spore masses of the fungus that causes FHB. If wheat blast symptoms are suspected, collect several heads from each field and send samples to the Purdue Plant and Pest Diagnostic Lab (PPDL) for confirmation: <http://www.ppdl.purdue.edu/PPDL/index.html>.

So why are we detecting wheat blast in the U.S. now? Researchers at the University of Kentucky suspect that fungal evolution may be the cause of the find. Variants of the fungus that causes wheat blast also cause a blast disease on rice, and gray leaf spot on annual and perennial ryegrass. Perennial ryegrass is a common turfgrass, and annual ryegrass is a popular cover crop species. Mark Farman at the University of Kentucky has studied the wheat blast fungus found in Kentucky and determined that it is more similar to the fungus that causes gray leaf spot on annual ryegrass than the fungus that causes wheat blast in South America. This suggests that the detection in Kentucky occurred as a result of the fungus evolving and expanding its host range from ryegrass to wheat, rather than an introduction of the fungus from South America.

Research is ongoing at several universities in the U.S. to understand the disease and determine how to best manage it should the need arise. We currently do not know the potential impact of this new disease in U.S. wheat, but early detection and documentation of the disease in Indiana will help us to prepare management strategies for the future.

![]()

Planting of the 2012 corn crop in Indiana got off to its earliest ever start. By April 8, an estimated 6 percent of the state’s corn crop was already planted and that increased to 24% by the following week (USDA-NASS, 2012). The early rush to begin planting corn was fueled by the unusually warm late March temperatures, soil conditions that were favorable for field activities and.................................. memories of the near-record breaking delayed planting of the 2011 corn crop. So, how is that crop faring nearly a month after some of it was planted?

Probably the best way to describe the general condition of the crop to date is that it is behaving like a crop that was planted in late March and early April. Some of it has been damaged not once, but multiple times by frost events in the past few weeks. Some of it has been lethally damaged by temperatures that dipped into the mid- to high twenties (F). Some fields experienced windy periods of “sand blasting” in recent weeks that damaged corn seedlings. Many of the surviving fields are light green to almost yellow. Almost all of the fields are developing slowly relative to calendar time, but on schedule relative to the more typical cool April temperatures and the resulting slow accumulation of growing degree days (GDDs).

Figure 1. Late V1 seedling on 27 April in a field planted 4 Apr 2012 in westcentral Indiana

During the last half of March, the unusually warm air temperatures translated to unusually warm soil temperatures such that the average daily accumulation of soil temperature-based GDDs was in the neighborhood of 8 to 12 GDDs per day in central Indiana. Considering that typical soil temperature-based GDD accumulation per day in late March is nearly zero, the 2012 experience was very unusual. Temperatures cooled off in April to normal or even slightly below-normal and, thus, daily GDD accumulation has also been fairly normal for April.............. meaning not very many GDDs per day (less than 10).

Corn requires about 115 soil temperature-based GDDs to emerge. After emergence and until about leaf stage V10, leaf collar emergence occurs about every 80 GDDs. So, for example, corn planted Apr 4 in westcentral Indiana would emerge in 115 GDDs or about 14 days after planting this year. Then 80 GDDs later, the plants would be at leaf stage V1. In westcentral Indiana this year, those 80 GDDs accumulated over another 9 days.

Nothing about this is unusual, but growers should recognize that early-planted corn in Indiana sometimes faces challenges not just from typical frost or freeze events in April, but also due to the fact that crop development in April is typically slow from a calendar perspective. The importance of this simple fact is that corn seedlings rely on kernel reserves to sustain their growth until the plants transition from dependence on kernel reserves to dependence on nodal roots. This transition period typically occurs around the V3 stage of leaf development.

The longer it takes corn seedlings to reach and successfully transition to dependence on nodal roots, the greater the risk that stand establishment will not occur successfully in terms of achieving a uniformly healthy stand of corn by the time the crop is knee-high. Damage to the kernel or mesocotyl by soil-borne insects (e.g., wireworms) or disease prior to the successful transition to dependence on the nodal root system will stunt or kill seedlings. Repeated damage to above-ground plant tissue by recurring frost events takes its toll on the health of the seedlings prior to the transition period also.

Hopefully growers who chose to plant in late March or early April hedged their bets by also applying a healthy rate of starter fertilizer in a 2x2 placement band. The role of starter fertilizer is to assist young corn plants as they make the transition from kernel reserves to nodal roots during times when root development or function is compromised by less than optimum growing conditions.

The forecast return of warm weather this coming week will certainly be welcomed by these early-planted fields, as will the forecast rainfall in areas of the state that have been unseasonably dry throughout much of late March and April.

Related Reading

Nielsen, RL (Bob). 2008. Use Thermal Time to Predict Leaf Stage Development in Corn. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. online at <http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/VStagePrediction.html> [URL accessed Apr 2012].

Nielsen, RL (Bob). 2010. Heat Unit Concepts Related to Corn Development. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. online at <http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/HeatUnits.html> [URL accessed Apr 2012].

Nielsen, RL (Bob). 2010. Root Development in Young Corn. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. online at <http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/Roots.html> [URL accessed Apr 2012].

USDA-NASS. 2012. Crop Progress. USDA National Ag Statistics Service. online at <http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/MannUsda/viewDocumentInfo.do?documentID=1048> [URL accessed Apr 2012].

![]()

Winter Wheat As A Forage – (Keith D. Johnson) –

- Some winter wheat hurt by recent freeze.

- Forage quality similar to perennial cool-season grasses.

- Wheat herbage yield reduced this year.

- Check with crop insurance agent.

Freeze damage was reported to have occurred again on some winter wheat fields in White and Carroll Counties. Questions about the value of winter wheat as a forage have been asked. Dry matter yield increases as winter wheat matures, but forage quality declines. Past research conducted in Indiana indicates that the crude protein content of winter wheat at the boot stage is 9.9 percent on a dry matter basis and declines to 4.6 percent when harvested at soft dough. Dry matter digestibility likewise declines as the crop matures, 68 percent at boot stage and 55 percent at soft dough. These values are similar to expectations of forage quality with commonly used perennial cool-season grasses. Dry matter yield of winter wheat forage is much less in 2012. Previous studies indicated three tons of dry matter per acre were possible at flower stage, but this will not be attained his year. Producers need to check with their crop insurance agent about options they have if contemplating using the wheat growth as a forage.

![]()

More Frozen Wheat: To Keep It or Not? - (Shaun N. Casteel) -

We, including myself, were optimistic for this year’s wheat crop – timely planting, good fall growth, and a jump on spring development with warmer temperatures in March. However, many fields of wheat have been hit with a sucker punch (or three) – freezing temperatures after greenup, limited water for growth and nitrogen uptake (especially with dry fertilizers like urea), and even some barley yellow dwarf.

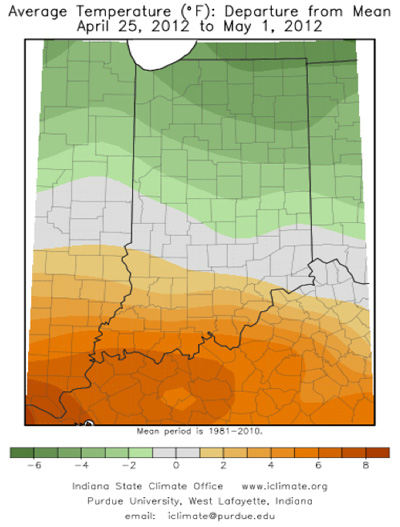

Indiana has experienced several weeks of cooler weather and nights that were near freezing in mid-April. Fortunately, most of our wheat (even the advanced wheat) was jointing at this time and the damage was only leaf tip burn (P&C 2012 issue 4). I did hear of a couple fields that showed freeze damage into the growing point (Figure 1) and lower stem (Figure 2). We thought we were out of the woods then temperatures last Thursday night (April 26) dipped below freezing again. Hard freezes (28°F) were noted in many areas in the northern third of the Indiana and wheat fields should be scouted now. Wheat was in the boot to heading stages when last week’s freeze came. The most severe period of damage usually occurs from the boot through flowering (P&C 2012 issue 4). I scouted several fields over the past few days with moderate to severe freeze damage (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Growing point killed by freeze – blacken growing point, but green leaves.

Figure 2. Freeze injury to lower stem – bruised appearance with a bend in the stem due to the tissue collapsing.

Figure 3. Severe freeze damage to a field in the boot stage. The sub-freezing temperatures settled into the field with the worst damage along the field edge. The temperatures were cold enough to freeze the flag leaves and the majority of the heads that were in the boot.

“Windshield” scouting is not suggested as many of the flag leaves were not burned with the recent freeze, so a drive-by will not always show the effects of the damage from the road (Figure 4). Younger wheat (prior to boot) will need to be split to determine if the growing point is dead (brown to blackish color). The leaves may still be green, but the growing point (the developing head) is dead (Figure 1). Emerged and emerging heads that are white have been frozen and the tissue is dead (Figures 4 and 5). Pale green portions of the head are questionable and further observation will be needed to determine the damage to the spiklets and anthers.

Figure 4. Flag leaf is green and undamaged, but the head that is in the boot was partially damaged from freezing temperatures. These symptoms are not visible from “windshield” scouting.

Figure 5. Emerging head that was in the boot when the freeze occurred 6 days prior to the picture. The awns and the head are whitish in color and the spikelets are dead. The spikelets on the lower, left side of the head were more protected and the damage is uncertain. Follow-up visits are required to determine the extent of damage to developing anthers.

The question is, “do I take it to yield or tear it up?” The decision needs to be weighed with the cascading effects on crop insurance, seed supply, crop rotation, manure application, calendar date, etc. I cannot address every scenario, but communication needs to be clear through all interested parties. Wheat is advanced for the time of the year, and assuming that harvest will be earlier, there will be greater opportunities for double-cropping soybeans further north than I typically recommend. A reduced wheat yield due to partial freeze damage may still work for those who could double crop soybeans.

Severely damaged fields from freeze or poor development have a few options for management: cut it for hay or wheatlage provided you have a market for it (see Keith Johnson’s article on forage quality), kill it with herbicide, mow it or till it. It is the first week of May, and we have plenty of time to establish a good crop of soybean or corn in these fields. The main point is to provide the best opportunity to establish a good stand and not to rush planting into wheat stubble or a matt of wheat residue without the proper planting equipment (i.e., planting “no-till” with equipment that isn’t set up for no-till).

Many options exist and should be explored for managing wheat that has been frozen or has low yield potential from other factors such as low water supply for nitrogen uptake, barley yellow dwarf, etc. Again, I highly suggest scouting wheat fields in the northern third of the state to assess any freeze damage and manage accordingly.

Further Reading

Pest&Crop Newsletter 2012, Issue 4. Freeze Injury in Wheat – S.N. Casteel. <http://extension.entm.purdue.edu/pestcrop/2012/issue4/index.html>.

![]()