Pest & Crop Newsletter, Entomology Extension, Purdue University

- Are Slugs Sliming Your Crop?

- Seedcorn Maggot Potential for Planted Soybean

- Black Light Trap Catch Report

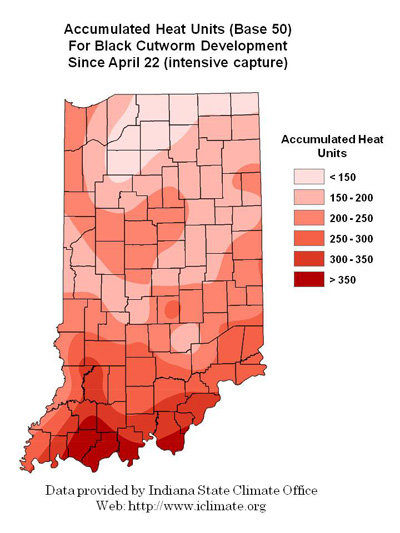

Are Slugs Sliming Your Crop? – (Christian Krupke and John Obermeyer)

- Slug damage is exacerbated in a cool, wet spring with heavy crop residue on the soil surface.

- Crop damage and stand losses are most severe when slugs enter open seed slots.

- Control options are limited and difficult to implement.

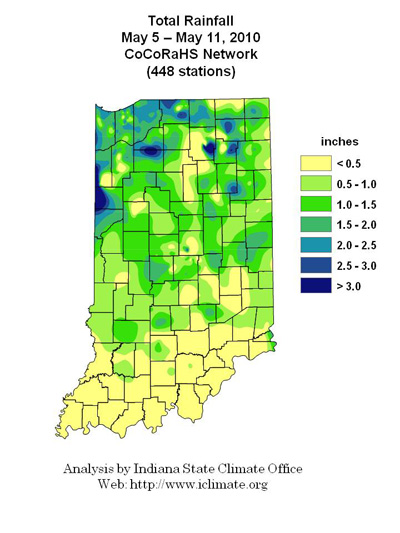

This wet weather got us thinking about a non-insect, pest of field crops – the lowly, slimy slug. Slugs, like all mollusks without shells, need relatively high humidity to thrive and seem to be more apparent during periods of persistent rainfall. When it comes to slugs, we are fortunate to have an expert in the Midwest: OSU extension entomologist, the venerable Dr. Ron Hammond. Dr. Hammond tells us that although slugs may seem to “like” this weather, damage to young corn and bean plants is more likely due to slug movement patterns – the main problem (as with many soil insect pests) is that the interface between slugs and slow-growing plant tissue are greater during these wet and cool periods.

Shredded corn seedling from slugs

Slugs are soft-bodied, legless, slimy, and grayish or mottled gastropods. Their length, depending on species, can reach up to 4 inches, but is usually 1/2 to 1-1/2 inches long. Build-up of slug populations is greatest in no-till systems and weedy fields, because the optimum conditions for slug survival (wet soils, lots of residue) are most likely to occur under these conditions. Juvenile slugs, which are present now, will continue to increase in size, as will their appetite. Depending on future weather, their feeding can continue well into June.

Both corn and soybeans can be significantly damaged by this nocturnal pest. Their mouthparts cause a scraping type of damage, where the top layer of leaf tissue is removed. On corn, slugs feed on the surface tissue of leaves resulting in narrow, irregular, linear tracks or scars of various lengths. Severe feeding can result in split or tattered leaves that resembles hail damage. Soybean damage is not as predominant on the foliage, but rather on the hypocotyl and cotyledons. Given good growing conditions, plants usually outgrow slug damage once the crop is up. Most damage and stand losses by slugs occur when fields are too wet to plant and seed slots are not properly closed. In this situation, slugs can be found feeding on the seedlings within the slot, day or night. Obviously, once the growing point of corn or soybeans is injured, plant recovery is unlikely.

Up close and personal with a slug

Control of slugs is difficult, if not impossible. Disruption of their environment, i.e., tillage, is typically not an option, especially on long-term no-till or highly erodible land. A metaldehyde-pelleted bait is labeled and available for use. However, spreading the pellets evenly over the field or damaged areas is another matter; a commercial mechanical dispenser is one possibility. Field trials at Ohio State have shown good results when the pellets are evenly distributed. With the significant cost and difficulty of application, consider these baits only as a last resort to protect crop stands in high slug populated areas.

Where replanting is necessary from slug damage, one should strongly consider lightly tilling the area first. This should help dry the area and break-up and bury crop residue. Doing so will discourage further slug activity. Granular, liquid, and seed-applied insecticides are ineffective against slugs, as they slime over them. Bt corn has no effect on slugs. Home remedies, such as spraying plants at night with liquid fertilizer (high salt concentration), have proved futile and are obviously impractical for most large-scale plantings.

![]()

Seedcorn Maggot Potential for Planted Soybean - (Christian Krupke and John Obermeyer)

- Seedcorn maggot are attracted to fields with abundant vegetation and/or animal manure.

- Winter annual weed control goes a long way in preventing infestations.

- Most corn seed is already protected by seed-applied insecticides, most soybeans are not.

- Evaluate fields to determine level of damage and need for replanting.

Planting activity was proceeding at breakneck speed before the rains began, still many fields of soybean remain to be planted. Some soybean planting was rushed and occurred in fields that had less than ideal seedbeds, meaning little to no weed control had been applied. Corn and soybean seeds planted in high crop residue, weedy growth, and/or where animal manure was applied are most often subject to attack by seedcorn maggot. You are familiar with the many drawbacks of planting into weedy fields, such as black cutworm, but seedcorn maggot is a potentially serious pest that is often forgotten.

Seedcorn maggot adults are small, extremely common flies (look like a minature housefly) that are attracted to all types of decaying matter in which to lay their eggs. Soils planted too wet are often improperly sealed, attracting flies to climb down into the furrow and deposit eggs in decaying weeds next to the seed. Soon the yellowish-white maggots, up to 1/4 inch long, burrow into the seeds or underground portion of plants and feed. The damage they cause can serve as an entry point for a range of other pests as well, including fungal and bacterial pathogens. All of this happens beneath the soil surface, so the damage is usually first observed as skips in the row where plants do not emerge, or if they emerge, die back. The problem will be worsened by cool-wet soils during the germination period.

Low rates of the neonicotinoid insecticides Cruiser (thiamethoxam) or Poncho (clothianidin) are on virtually all corn seed sold in Indiana and both are very effective on seedcorn maggot. On the other hand the majority of soybean seed is not treated with an insecticide and would be prone to damage if planted into weedy/manured fields. Should replanting be necessary, insecticide on the soybean seed (i.e., Cruiser or Gaucho) is probably not necessary, as the seedcorn maggot will probably have already pupated and soon to emerge as an adult fly. In other words, the damage window will have closed.

Seedcorn maggot damaged cotyledons

Seedcorn maggot pupa, indicating damage is complete

![]()

![]()

Click here to view the Black Light Trap Catch Report

![]()

Dame’s Rocket – (Glenn Nice, Bill Johnson, Tom Jordan, and Tom Bauman)

Although I, Glenn, generally keep most of my attention on the road when I am driving (while Bill is often playing on his phone), I often keep my reserve attention on the fields and roadsides as I pass. Lately I have been seeing a fair amount of a purple plant blooming on the roadsides (Figure 1.) At closer inspection, the plant of interest is turns out to be dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis).

Figure 1. Roadside with pathes of Dame's rocket

Description

Dame’s rocket has showy purple, pink to white flowers (Figure 2). Flowers are 0.7 to 1 inch wide[1]. A member of the mustard family, it has four distinct petals that bloom from spring through the summer. Plants are unbranched below, but branch in the upper portion of the plant and can grow from two to three feet tall with the upper branches growing out of leaf axils. Leaves are hairy on both sides, 3 to 8 inches long, lance shaped, with either dentate or slightly toothed margins. The leaves are narrow at the base, being either sessile or with short petioles (Figure 3). Dame’s rocket produces pods that are cylindrical and two to four inches long (Figure 4)[1]. Dame’s rocket is sometimes reported to be a biennial or perennial. Germination appears to be optimum in warmer temperatures and on the soil surface. Susko and Hussein (2008) reported up to 80% seed germination with a day/night temperature of 77/59°F. However, 68/50°F temperatures reduced germination to about 10% [Susko]. Emergence occurred from up to four inches deep in the soil, but decreased from close to 100% on the surface to almost 0% at 4 inches[2].

Figure 2. Dame's rocket flowers

Figure 3. Dame's rocket linear leaves and branching from axils

Figure 4. Dame's rocket seed pod

Background

Originally from Eurasia, Dame’s rocket was suspected to have been brought over to the US in the 1600’s[3]. Its showy flowers and fragrance can make it popular for the garden. Used in gardens in Europe, it was reported in a historical list of seeds that could be planted in both winter and summer[4]. It was also used in the past as a house plant[5]. Somewhat naturalized in the U.S. (been here for a long time) it is often mistaken for being a native species, sometimes being found in native species seed mixes, although it is not a native plant [6]. Dame’s rocket often appears as an escaped plant on roadsides and fields as reported in “An Illustrated Flora of the Northern United States and Canada,” by N. Britton and A. Brown published in 1913. Dame’s rocket is reported on roadsides[1]. There was no record in Indiana of it in 1899, but in 1940 Deam reported records of Dame’s Rocket in seven Indiana counties. More recently in surveys by William and Edith Overlease, it was reported in 91 of Indiana’s 92 counties[7]. Dame’s rocket is on the invasive plant list for the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystems Health web site <http://www.invasive.org>. It is listed as “Do not buy, sell or plant in Indiana” by the Indiana Invasive Plant Species Assessment Working Group [IPSAWG]. The States of Colorado, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Tennessee have listed Dame’s Rocket as noxious weeds or as an exotic pest.

Control

Dame’s rocket still seems to have appeal and would seem not to have been condemned as a weed. This, in part, has lead to it being over looked for weed control efforts, since no research has been done on Dame’s rocket when it comes to its control. Pulling plants or mowing Dame’s rocket might have an impact on populations and seed production. As far as herbicides go, no labels or publications could be found that had information on Dame’s rocket control with any herbicide.

Reference:

1. N. Britton and A. Brown. 1913 reprinted 1970. “An Illustrated Flora of the Northern United States and Canada.” Dover Publications, Inc. New York. Vol. 2, p. 175.

2. D.J. Susko and Y. Hussein. 2008. Factors affecting germination and emergence of Dame’s rocket (Hesperis matronalis). Weed Science 56:389-93.

3. H.A. Gleason and A. Cronquist. 1991. “Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. New York: New York Botanical Garden. p. 910.

4. J. Harvey. 1995. An Elizabethan seed-list. Garden History. Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 242-245.

5. J. Woudstra. 2000. The use of flowering plants in late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century interiors. Gardening History. Vol. 28, No. 2 pp. 194-2085.

6. USDA Forestry Service. 2006. Weed of the Week: Dame’s Rocket.

7. W. Overlease and E. Overlease. 2007. “100 Years of Change in the Distribution of Common Indiana Weeds.” Purdue University Press. p. 83.

8. Landscaping with Non-Invasive Plant Species: Making the Right Choice. Indiana Invasive Plant Assesment Work Group.

![]()

Weather Related Weed Management Items – (Bill Johnson and Glenn Nice)

Recent wet, rainy weather has created some weed management challenges for Indiana growers. In this article we will hit on a few key points to consider based on current challenges.

Delayed weed control in corn. Indiana corn growers rely heavily on atrazine premixes in corn. Rain will not have completely washed all of the herbicide away, but may have compromised overall activity. Scout fields as soon as possible to determine if weeds are escaping. Obviously giant ragweed is a big concern, but wet conditions and dilution of atrazine can result in failures to control cocklebur, sunflower, velvetleaf, burcucumber, morningglories, and waterhemp. If corn is less than 12 inches tall and you haven’t used all of the atrazine allowed by the label, it would be wise to add atrazine to the other postemergence herbicides being applied to corn to control the above mention weeds and provide some soil residual activity. If corn is more than 12 inches tall, you cannot use any additional atrazine.

Weed escapes in large corn in all of Indiana. When the warm weather hits us late this week and through the weekend, corn will grow rapidly. Postemergence corn herbicide options become limited when corn is 12 inches tall, and really limited on corn at the V6 or later growth stage. Also keep in mind that large weeds are much more difficult to control. To avoid crop injury on corn under other stresses, try to keep spray out of whorls, especially with ALS inhibitors and contact products. See table 6 in the weed control guide for the height restrictions of postemergence corn herbicides.

See Table 6. Rainfast Intervals, Spray Additives, and Maximum Crop Size for Postemergence Corn Herbicides from the Weed Control Guide For Ohio and Indiana <http://www.btny.purdue.edu/Pubs/WS/WS-16/CornRainFast.pdf>.

Big Bad Broadleaves. Be on the lookout for giant ragweed and burcucumber. Every year is a good one for giant ragweed, and frequent rains are good for burcucumber. Both weeds have relative long emergence patterns and herbicides with both foliar and residual activity are needed. If corn is not 12 inches tall, consider adding some atrazine to the postemergence product to extend the residual window of activity on these weeds.

How do I pick a postemergence herbicide for corn? Going on the assumption that most of the corn grown in Indiana is Roundup Ready or Liberty Link, we assume growers will use glyphosate or Ignite as the base herbicide. Many different herbicides can be tankmixed with glyphosate or Ignite to broaden the spectrum of weeds controlled and provide residual activity in the soil. The best advice we can give you is to consult table 4 on page 28 of the weed guide to help in selecting tankmix partners for weeds you are trying to control.

See Table 4. Weed Response to Postemergence Herbicides in Corn from the Weed Control Guide For Ohio and Indiana <http://www.btny.purdue.edu/Pubs/WS/WS-16/CornHerbRating.pdf>.

Large weeds in fields intended for soybean. We have observed some fields (both planted and unplanted) with dandelions flowering for the second or third time, cressleaf groundsel in excess of 3 feet tall, common pokeweed, hemp dogbane, and milkweed in excess of 2 feet tall, and flowering thistles. In no-till fields that have not yet been planted, increase glyphosate rates for burndown to at least 1.5 lb ae/A to improve control of large weeds. Wait at least 1 day before pulling a drill or planter through the field to allow the weeds to absorb glyphosate. Since it is late in the spring, if marestail is present, add FirstRate or Classic or Sharpen to glyphosate. If you know the marestail is ALS resistant, add Sharpen to glyphosate.

In fields that will conventionally tilled, consider using no-till instead. It is difficult to completely control large down large weeds which then recover and become difficult to control with herbicides. If you do conventional tillage and have weeds in excess of 1 foot tall, apply glyphosate prior to tillage to ensure effective control. Wait at least one day between glyphosate application and tillage for annual weeds, and 2 to 3 days for perennial weeds. The good news is that glyphosate products work much more rapidly when air temperatures are high and knockdown activity will be more rapid than we are used to with early spring applications.

![]()

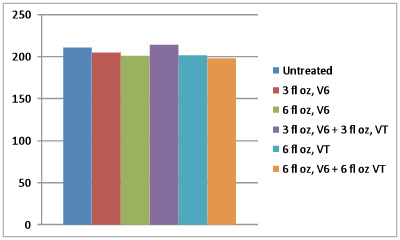

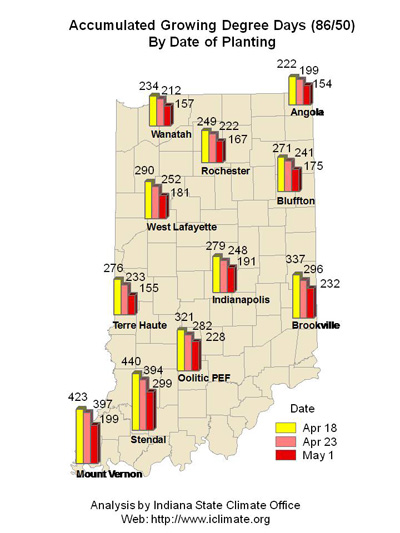

Early Fungicide Applications in Corn – (Kiersten Wise)

Corn is already at V3 or later in early plantings in Indiana, and many producers may be considering an early fungicide application to corn when fields dry out.

Early fungicide applications are a new trend in field crop production, and are reported to increase yield even in the absence of significant disease or a disease threat. The timing of an early fungicide spray coincides with post-emergence herbicide applications, making them easier and possibly cheaper to apply than later fungicide applications that target the tasseling or VT growth stage. However, there is not an extensive amount of replicated research that shows a consistent yield benefit from early fungicide applications to corn.

This topic has been discussed by other University researchers in the Midwest (1,2). This winter, data was collected from trials conducted across the Midwest and summarized by Carl Bradley at the University of Illinois. Most locations included the fungicide Headline, and therefore this product was compared across locations. Although Headline is the only product discussed in the regional summary and in this article, there are several other strobilurin or strobilurin/triazole premix fungicides that have been marketed for use in early application systems. Regional trials compared a Headline application at V6 (6 fl oz) with a Headline application at VT-R1 (6 fl oz), and an untreated control. Results of the regional summary can be viewed here: <http://ipm.illinois.edu/bulletin/article.php?issueNumber=3&issueYear=2010&articleNumber=6>.

The Indiana trial included in the regional summary was conducted at the Southeast Purdue Agricultural Center in Jennings county, IN. In this trial, a V6 application of fungicide at 3 fl oz or 6 fl oz did not increase yield compared to the untreated control (Figure 1). Gray leaf spot developed late in this trial with very low levels of the disease present on lower leaves at the time of the VT application, which may have influenced the yield response in this trial. In the regional trial, locations with high disease pressure did see a more favorable yield response from a VT-R1 application. The average yield response over all regional trials for a VT-R1 application was 8 bushels/acre, compared to 1.5 bushels/acre for the V6 application.

Figure 1. Yield of corn treated with Headline fungicide applied at the V6 or VT growth stages in corn at the Southeast PUrdue Agricultural Center in 2009. LSD=NS

It is important to remember that a V4-V6 application of fungicide to corn will not protect the ear leaf or above from disease that develops around tasseling. Ultimately, the most consistent yield advantage from a fungicide application appears to be when the product is applied in situations where there is a high risk of disease development at VT-R1. Hybrid susceptibility, previous crop, and weather strongly influence disease development, and these factors should be considered before deciding on a fungicide application.

1. Bradley, C.A. 2010. Fungicide Applications to Corn at Early Growth Stages. The Bulletin, University of Illinois. Vol. 3:6. <http://ipm.illinois.edu/bulletin/article.php?issueNumber=3&issueYear=2010&articleNumber=6>

2. Vincelli, P. 2010. Testing for a Benefit of Fungicides on Early Growth Stage Corn. Kentucky Pest News. No. 1226: <http://www.ca.uky.edu/agcollege/plantpathology/extension/KPN%20Site%20Files/kpn_10/pn_100420.html>.

![]()

Wet Soils Favor Seedling Blights in Corn and Soybean – (Kiersten Wise)

Frequent rains over the last three weeks have left many pockets of wet soils in fields. Plants may not have emerged from these low-lying areas yet, or if plants have emerged, stand may be uneven and seedlings are exhibiting reduced vigor. There are many reasons for poor emergence and stunted seedlings, including environmental stress, but seedling blights might also be to blame.

Seedling blights are prevalent when cool, saturated soil conditions persist after planting. These conditions favor germination and infection by many of the organisms that cause soil-borne diseases. Cool, wet soils also slow plant growth and development and give diseases more time to infect and damage the seedling.

Seedling blights are caused by a variety of soil or seed-inhabiting fungi. Infected seeds may rot after germination, preventing emergence, and plants that emerge have reduced root development and are often stunted. Roots of infected plants may be brown and discolored and can be soft or mushy (Figure 1). Infected plants may also have brown discoloration on the mesocotyl. It is difficult to determine in the field which disease is to blame for a specific case of seedling blight, and it may be necessary to submit a sample to get an accurate diagnosis.

The risk of seedling blight development decreases when crops are planted into warm, dry soils. These conditions allow seedlings to germinate and emerge rapidly. However, it is often necessary to plant into less than ideal soil conditions, and fungicide seed treatments provide some protection against seedling blights. Most corn is currently treated with a combination of fungicides that protect against both diseases caused by true fungi and fungal-like organisms, known as water molds. Replanted soybeans should be treated with suitable seed treatments that protect against fungal organisms (Fusarium, Rhizoctonia), and water molds like Pythium and Phytophthora.

Figure 1. Pythium seedlingt blight on corn (Photo Credit: G. Ruhl)

![]()

Monitor Fusarium Head Blight Risk in Northern Indiana Wheat – (Kiersten Wise)

- Wheat is at a critical growth stage for disease development in northern Indiana.

Wheat is heading and beginning to flower in areas in central and northern Indiana. These regions are at low to moderate risk for Fusarium head blight development for wheat that will flower during the next few days. Rainy weather over the last week has increased risk in portions of the state, and producers in areas where wheat is beginning to flower should carefully monitor the risk map over the coming week:<http://www.wheatscab.psu.edu>. If wet, humid conditions persist, risk for disease development could increase in other northern and central counties in the state.

Producers in areas of medium risk that are wary of model predictions and have Fusarium head blight-susceptible varieties planted may choose to apply a fungicide. Fungicide applications need to be made at Feekes 10.5.1, or early flowering. There are several fungicides available for Fusarium head blight control, and these are listed in the foliar fungicide efficacy table developed by the North Central Regional Committee on Management of Small Grain Diseases or NCERA-184 committee: <http://www.ppdl.purdue.edu/ppdl/wise/NCERA_184_Wheat_fungicide_chart_2010_v2.pdf>

Caramba, Prosaro, and Proline were given a rating of “good” based on a designation system from the Regional Wheat Disease Committee. Products containing only tebuconazole (Folicur, others) were rated as fair, and propiconazole alone (Tilt, others) was rated as poor for management of Fusarium head blight. Fungicides that have a strobilurin mode of action are not labeled for Fusarium head blight suppression. Be sure to follow label restrictions on how many days must pass between fungicide application and harvest.

Foliar diseases such as Septoria/Stagonospora leaf blotch have been observed in fields throughout the state, but are still at relatively low levels. Very low levels of stripe rust and leaf rust (low incidence and severity) were first reported in southern IN last week in Spencer county and Knox county, respectively.

Prevalent Purple Plants Perennially Puzzle Producers – (Bob Nielsen)

Like the swallows that return to Capistrano, it seems that purpling in young corn returns every year somewhere in Indiana. Today I spotted some young corn plants (V3 to V4) with leaves that were noticeably purplish-red. The purplish plants were more prevalent in the wetter areas of the field and almost non-existent in the drier areas. While mildly attractive from an ornamental standpoint, landlords and tenants alike often become concerned when they see their fields take on a purplish hue that is clearly evident from the window of the pickup at 60 mph.

A very late V3 corn plant exhibiting purple leaves

Purpling of corn plant tissue results from the formation of a reddish-purple anthocyanin pigments that occur in the form of water-soluble cyanidin glucosides or pelargonidin glucosides (Kim, 1998). A hybrid’s genetic makeup greatly determines whether corn plants are able to produce anthocyanin. A hybrid may have none, one, or many genes that can trigger production of anthocyanin. Purpling can also appear in the silks, anthers and even coleoptile tips of a corn plant.

Well, you may say, that’s fine but what triggers the production of the anthocyanin in young corn at this time of year? The answer is not clearly understood, but most agree that these pigments develop in young plants in direct response to a number of stresses that limit the plants’ ability to fully utilize the photosynthates produced during the day. These stresses include cool night temperatures, root restrictions, and water stress (both waterlogged and droughty conditions).

There’s no question that many corn fields throughout the state have suffered through wet soil conditions during the past several weeks. Soil compaction (tillage- or planter-related) can also restrict the development of the initial root systems. The additional stresses imposed by quite a few relatively cool nights (upper 30’s to low 40’s) and the occasional bright sunny days (high levels of visible and UV radiation) may be the final “triggers” that result in fields of pretty purple plants.

Since the anthocyanin occurs in the form of a sugar-containing glucoside, the availability of high concentrations of sugar in the leaves (photosynthesis during bright, sunny days) further encourages the pigment formation. If fields are stressed by other factors such as soil compaction, herbicide injury, disease damage, or insect injury, the purpling becomes even more pronounced.

It has been my experience that the combination of bright, sunny days and cool nights when corn ranges from V3 to V6 in development (3- to 6-leaf collar stages) most commonly results in plant purpling. Hybrids with more anthocyanin-producing genes will purple more greatly than those with fewer “purpling” genes. In most cases, the purpling will slowly disappear as temperatures warm and the plants transition into the rapid growth phase (post-V6).

I have rarely diagnosed phosphorus deficiency as the primary cause of purple plants early in the season. Nonetheless, cold or wet soils inhibit root development and can aggravate a true phosphorus deficiency situation, frequently causing even more intense leaf purpling.

What About Yield Losses? Does the leaf purpling lead to yield losses later on? The cause of leaf purpling, not the purpling itself, will determine whether yield loss will occur by harvest time.

If the main cause is the combination of bright, sunny days and cool nights, then the purpling will disappear as the plants develop further with no effects on yield. If the stress of restricted root systems is a major contributor to the purpling, then the potential effects on yield depend on whether the root restriction is temporary (e.g., cool temperatures & wet soils) or more protracted (e.g., soil compaction, herbicide injury). Plants can recover from temporary root restrictions with little to no effect on yield. If the root stress lingers longer, the purpling may continue for some time and some yield loss may result if the plants become stunted.

Related References

Chalker-Scott, Linda. 1999. Environmental Significance of Anthocyanins in Plant Stress Responses. Photochemistry and Photobiology 70(1): 1–9.

Christie, P.J., Alfenito, M.R., and Walbot, V. (1994). lmpact of low- temperature stress on general phenylpropanoid and anthocyanin pathways: Enhancement of transcript abundance and anthocyanin pigmentation in maize seedlings. Planta 194: 541-549.

Dixon, Richard A. and Nancy L. Paiva. 1995. Stress-lnduced Phenylpropanoid Metabolism. The Plant Cell 7:1085-1097. American Society of Plant Physiologists. [On-Line]. Available at <http://www.plantcell.org/cgi/reprint/7/7/1085>. [URL accessed May 2010].

Kim, Jae Hak. 1998. Maize Anthocyanin Pathway. Pennsylvania State Univ. [On-Line]. Available at <http://scripts.cac.psu.edu/courses/plphy/plphy597_hef1/mpath.html>. [URL accessed May 2010]. Editorial note: This link is for biochemistry fans!

Nielsen, R.L. (Bob). 2009. Reddish-Purple Corn Plants Late in the Season. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. [online]. <http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/PurpleCorn2.html> [URL accessed May 2010].

The 2010 Purdue Weed Day is scheduled for Thursday July 1, 2010. The program will begin at 8:30 AM Eastern Daylight Time (Central Daylight Time) at the Throckmorton Purdue Agricultural Center, 8343 US 231 South Lafayette, IN 47909-9049. The farm is located approximately 5 miles south of Lafayette on the corner of county road 800S and U.S. 231 South. Come a little early and have coffee and a doughnut with us. Water and soft drinks will be available during the tour. For those attending the 2010 Purdue Weed Day, we have applied for 3 CCH’s for category 1.

Weed pressure is quite good and early postemergence treatments will soon be applied. The herbicide plots will give you a chance to look at new herbicides and how they compare to the products currently on the market. We will also have trials to address the competitive effects of volunteer corn on soybean and corn yields and how to control it. In addition, our weed science graduate students will be available to discuss their research projects.

An attendance form is located on the Purdue Weed Science Website at <http://www.btny.purdue.edu/WeedScience/Temp/WeedDay2010.html>. Please fill out and return the form if you plan to attend. This will allow us to maintain a mailing list and to estimate coffee, doughnut and soft drink needs for the Weed Day.