Pest & Crop Newsletter, Entomology Extension, Purdue University

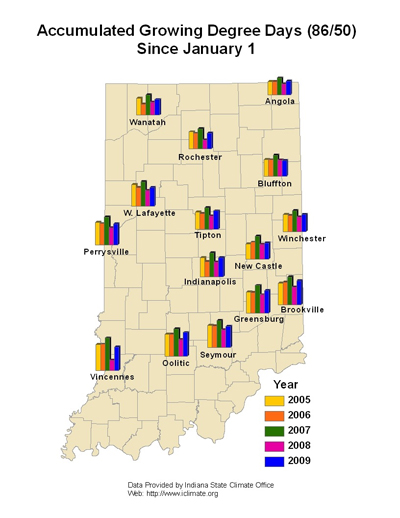

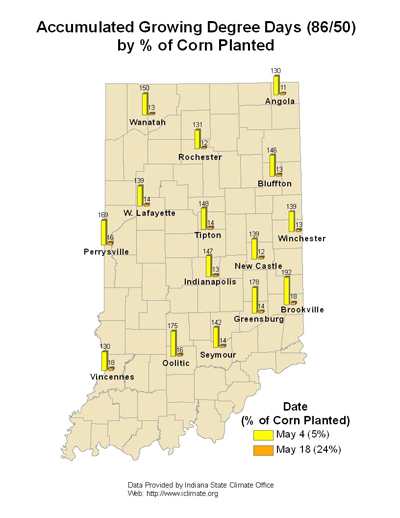

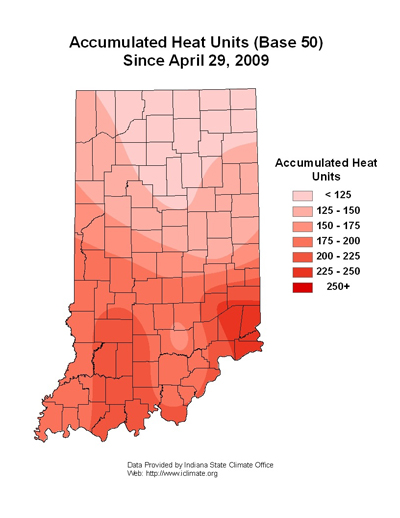

Planting is Delayed, So is Insect Development…Don’t Forget Rootworm Protection – (John Obermeyer and Christian Krupke)

Some will remember that 2002 had a horrendous start to the growing season, first planting was delayed by excessive rains, followed by a long, hot dry spell. That year, producers pushed the window and planted into wet soil creating side-wall compaction. Producers were so hurried that inputs such as soil insecticides for rootworm protection were neglected in some cases. When the drying occurred, the top inches of soil baked, becoming rock hard. The end result was that a rootworm population that was not excessive caused high levels of damage by feeding upon puny, misshapen, and slow-growing roots causing plant lodging, “small corn-tall corn,” and sometimes plant death. The amount of damage a root system can take is proportional to its overall size – this is important to remember in years like this one.

Puny root system and rootworm feeding

By the calendar, rootworm should soon begin hatching, a process that goes on for several weeks. However, this year the calendar does not tell the full story. The cool soil temperatures have not only delayed soil drying and/or corn emergence but rootworm development as well. Rootworm development only occurs at temperatures above 52°F. This provides a “safety valve” of sorts for the insect by synchronizing them with development of the corn plant, their only host – in other words, if conditions are not suitable for corn growth and development, chances are they will not be suitable for rootworm egg hatch. Although daytime temps have been warmer than 52°F recently, cold nights have meant that the soil temperatures 4” or more below the surface (where rootworm eggs are), have stayed low – as anybody who has dug into Indiana fields and felt the soil can attest. Bottom line: with much of Indiana’s corn yet to be planted in rootworm risk areas (i.e., most of the state, particularly north of I-70), rootworm protection should still be used. For those planting seed with Bt-RW technology, don’t forget to protect the refuge.

![]()

Replanting Corn and Rootworm Insecticide Restrictions - (Christian Krupke and John Obermeyer)

Soil insecticides have restrictions as to the amount of product that can be applied per season as stated on the label. Because the label is the law, this is not to be exceeded. Most soil insecticide rates restrict application to one per season. Lorsban 15G (4E) can be legally reapplied if you observe the 16-ounces per 1000 ft. of row (6 pints per acre) per season limit. The seed-applied insecticides (SAI), Cruiser and Poncho, can also be reapplied. The bottom line is that, if you choose to reapply a soil insecticide during replanting, it should be a different active ingredient from what you used the first time (exception is Lorsban and SAIs). Remember, your granular insecticide boxes will have to be recalibrated for the new product since all products are formulated differently. Of course, Bt-RW products are not subject to any such restrictions, as they are not considered “insecticides” in this way.

| Product | Replant Restriction at Rootworm Rate (Use Same Product Again?) |

| Aztec 2.1G & 4.67G | Don't |

| Capture 2EC & LFR | Don't |

| Counter CR & 15G | Don't |

| Cruiser (rootworm rate) | Yes |

| Force 3G & CS | Don't |

| Fortress 2.5G & 5G | Don't |

| Furadan 4F | Don't |

| Lorsban 15G & 4E | Yes |

| Poncho 1250 (rootworm rate) | Yes |

| Regent | Don't |

![]()

![]()

Bug Scout Says: "Find a time to scout emerging cornfields

Bug Scout Says: "Find a time to scout emerging cornfields

for black cutworm damage"

![]()

Click here to view the Black Light Trap Catch Report

![]()

Considerations for Replanting Soybean in Drowned Out Corn Fields – (Bill Johnson and Glenn Nice)

The recent heavy rains have resulted on lots of standing water and drown out areas in corn and soybean fields. Many of these areas will require replanting. A major consideration on whether to replant soybean in a field that was in corn is the rotational restrictions for corn herbicides. Table 22, see link below, (page 189-190) lists the rotational restrictions of the herbicides in the Weed Control Guide for Ohio and Indiana. The only herbicides labeled for use in corn which would allow replanting soybean immediately are Prowl and Python. All other soil applied corn herbicides have a several month rotational interval which must elapse before soybean can be planted. Most of the post emergence herbicides have shorter rotational intervals, but would still require a couple of weeks before soybean can be planted. Click on the link to view Table 22 <http://www.btny.purdue.edu/Pubs/WS/WS-16/HerbCropRot.pdf>.

![]()

The Who’s Who of Clovers – (Glenn Nice and Bill Johnson)

In forages, clovers are often the legume component in legume/grass mixtures. Other clovers are used to reduce soil erosion and yet other pesky clovers can be found in our lawns. Often when one thinks of clovers they are clumped together as one group, but the fact is that the clovers are a diverse group of plants. Many of the clovers found in Indiana have been introduced to the U.S. and some of those introduced clover are regarded as invasive species. The understanding of “the who’s who of clovers” even gets more complicated when you consider that several species of clovers have different varieties. The following article will try and shed some light on the many different clovers out there and point out the ones labeled as “invasive species.”

Meet The Clovers

The word “clover” is connected to many different plants in several genera from a few different plant families (Table 1). There are the waterclovers from the genus Marsilea spp., an aquatic plant that resembles a clover with four leaves but is not even in the clover family. In Indiana, the European waterclover (Marsilea quadrifolia) has been reported by the USDA plant data base to be in Clark county. Rough Mexican clover (Richardia scabra) is another plant that has been dubbed a clover only by title alone. It is a member of the madder family (Rubiaceae), distant cousin to velvetleaf. However, it is the clovers that are members of the legume family that are used as forages.

Most of the clovers we use as forages are from the genera trifolium spp. and Melilotus spp. The value of these clovers is using them in a symbiotic relationship with forage grasses for the purpose of fixing available nitrogen. These qualities have been promoted for some time in agriculture. The 1908, the Yearbook of the Department of Agriculture reported the value of “The perennial clovers, such as red, sapling, and alsike clover…” due to their ability to fix nitrogen and its tap root and soil health1.

The “Purdue Extension Forage Field Guide” provides information on some of the more common clovers in Indiana. Alsike, red, sweet, and white clovers are considered to be some of the more commonly used clovers as forages. One of the reasons these clovers have found favor in pastures in Indiana is that they can thrive on poorly drained soils with medium fertility, where alfalfa, Indiana’s other legume does best on well drained soils with high fertility. Areas that are not suited for alfalfa are often planted to clovers or grass clover mixes. The success of clover has lead to the development of different types and varieties.

White clover varieties are almost identical except for stature. Ladino and Regal have longer petioles and are often referred to as large white clovers2. There are medium sized clovers, such as Dutch or common white, and there are the small clovers. These are all technically white clover (Trifolium repens).

All species of clover are used by honey bees as a valuable source of nectar, and in Indiana clovers are a very important and main source of nectar. Clover honey is often favored due to its light color and flavor.

Are Clover Considered to be Invasive Species?

Many of the clover species that we use as forage have been introduced to the U.S. Sweet clovers, white clover, and crimson clover, have all been introduced. Does this mean that we should stop using these clovers? Are all these clovers considered to be invasive species? The introduction of a plant species does not always mean that the plant in question will become invasive. Soybean was introduced to the U.S. and has not made any invasive species lists. The invasive nature of a plant may also be impacted by the environment in which it exists. Labeling a plant invasive often leads to legislation and regulation to manage that plant. In some case like that of leafy spurge, introduced honeysuckle, giant hogweed, cogongrass in the south and others, the impacts can be clearly identified. Other introduced plants may not be so obvious, and the value of the plant will play a role in the debate on its negative impact.

The Federal Noxious Weed List does not include any of the clovers3. However, The Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health has listed several introduced clover species as invasive species4. In Indiana, clovers are not regulated by law, but we have listed the sweet clovers as unwanted pests at the “Most Unwanted” Invasive Plant Pests: Indiana Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) Program5. The Indiana Invasive Plant Species Work Group (IPSAWG) assessed sweet clover’s invasive potential. It was reported that sweet clover ranked low in impact, medium in potential to be problematic, medium in difficulty to control, but high in commercial value. The recommendation they presented goes as follows:

“Do not sell, buy, or plant yellow or white sweetclover in Indiana except where used for soil fertility and only if the sweetclover is not allowed to set seed. If existing stands of sweet clover are being used as a nectar source for bees, we recommend best management practices be used to limit its spread. It should not be planted near water (which spreads the seed) and mower decks should be cleaned before leaving the site. We also recommend that beekeepers rely on native nectar sources where possible . . . 6.”

The IPSAWG recommendations also provide alternative native species. For bees they recommend rosinweed (Silphium spp.), cupplant, (S. perfoliatum), prairie dock (S. terebinthinaceum), compass plant (S. laciniatum), native wild senna (Senna spp.), wild bergamot (Monarda clinopodia), joe pye weed (Eupatorium purpureum), boneset, (Eupatorium perfoliatum) and mountain mint (Pycnanthemum spp.)6.

Native Clovers

In north central region there are few native clovers. Some prairie clovers (Dalea spp.) are promoted as native alternatives. Purple prairie clover (D. purpurea) is sometimes used in native plant mixes. Two native clovers from the Trifolium genus are buffalo clover (Trifolium reflexum) and running buffalo clover (T. stoloniferum). In 1997, Taylor and Campbell of the University of Kentucky remarked that these two native clovers would probably not become valuable forage species due to scarcity of plants and are near extinction7. Running buffalo clover is recognized as an endangered species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service8.

McGraw et. al., (2004) looked at the forage quality of several native legumes including white prairie clover and purple prairie clover Ttable 2). When forage quality is the only consideration of selection, the native legumes did not fare as well as introduced species, having less crude protein and more cell wall fiber9.

Conclusions

In Indiana only the sweet clovers have been assessed for their potential to become invasive. In this process the sweet clovers were identified as being of low impact, medium potential of being problematic, but of high value. It is suggested that if possible to refrain from using sweet clovers and if used to take extra precautions to inhibit their unsolicited spread. As for the other clovers, they are not presently on any Indiana based invasive species list that I am aware of and are still used as valuable forages and for bees.

References:

1. Year Book of the United State Department of Agriculture. 1909. USDA. Government Printing Office. P. 412.

2. White Clover. Agronomy Facts 22. PennState Collage of Agriculture Sciences, Cooperative Extenion.

3. Federal Noxious Weeds. Accessed 4-20-09. USDA. <http://plants.usda.gov/java/noxious?rptType=Federal>.

4. Invasive.org: Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health. Accessed 4-17-2009. <http://www.invasive.org/species/weeds.cfm>.

5. Most Unwanted” Invasive Plant Pests: Indiana Cooperative Agricultural Pest Survey (CAPS) Program. Accessed 4-17-2009. <http://extension.entm.purdue.edu/CAPS/plants.html>.

6. Official Assessment of Sweetclover in Indiana’s Natural Areas. Indiana Invasive Plant Species Work Group. Accessed 4-17-2009. <http://www.in.gov/dnr/files/Official_sweet_clover_assessment.pdf>.

7. AGR-142. N.L. Taylor, Department of Agronomy and J.N.N. Campbell. University of Kentucky. <http://www.ca.uky.edu/agc/pubs/agr/agr142/agr142.htm>.

8. Running Buffalo Clover. 2003. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. <http://www.fws.gov/midwest/endangered/plants/pdf/rbc-fctsht.pdf>.

9. Native Legume Species for Forage Yield, Quality and Seed Production. R.L. McGraw, F.W. Shockley, J.F. Thompson, and C.A. Roberts. Native Plants Journal. Vol. 5(2) pp 152-160.

10. USDA Plant Data Base. Accessed 4-20-09. <http://plant.usda.gov>.

| Table 1. Plants with the name clovers found in and around the State of Indiana10 | |||

| Genus | Species | Common Name | Comments |

| Dalea | candida | White prairie clover | Native Can be found in native plant mixes [JFNEW]. |

| leporina | Foxtail prairie clover | Native | |

| purpurea | Purple prairie clover | Native Can be found in native plant mixes. | |

| Kummerowia | striata | Japanese clover | Introduced |

| Marsilea | quadrifolia | European waterclover | Introduced |

| Medicago | minima | Little bur-clover | Introduced - same genus as alfalfa

|

| polymorpha | Burclover | Introduced - same genus as alfalfa | |

| Melilotus | altissimus | Tall yellow sweetclover | Introduced |

| indicus | Annual yellow sweetclover | Introduced - invasive | |

| officinalis | Yellow sweetclover | Introduced | |

| Orthocarpus | luteus | Yellow owl's-clover | |

| Richardia | scabra | Rough Mexican clover | Rubiaceae family, madder family |

| Trifolium | arvense | Rabbitfoot clover | Introduced |

| aureum | Golden clover | Introduced | |

| campestre | Field clover | Introduced | |

| dibium | Suckling clover | Introduced | |

| flagiferum | Strawberry clover | Introduced | |

| hybridum | Alsike clover | Introduced | |

| incarnatum | Crimson clover | Introduced | |

| medium | Zigzag clover | Introduced | |

| pratense | Red clover | Introduced | |

| reflexum | Buffalo clover | Native | |

| repens | White clover | Introduced | |

| resupinatum | Reversed clover | Introduced | |

| stoloniferum | Running buffalo clover | Native | |

| Table 2. Forage yield and quality of white prairie clover and purple prairie clover | |||||||

| Native Legume | Yield |

Yield (Mature) |

NDF | ADF | Crude Protein | Seed Yield | Seed/Plant |

| oz/plant | oz/plant | oz/plant | |||||

| White prairie clover | 0.4 | 0.2 | 50% | 0.01% | 13% | 0.004 | 77 |

| Purple prairie clover | 0.4 | 0.8 | 47% | 0.21% | 15% | 0.07 | 1441 |

| Adapted from R.L. McGraw, F.W. Shockley, J.F. Thompson, and C.A. Roberts9 | |||||||