Pest & Crop Newsletter, Entomology Extension, Purdue University

Western Bean Cutworm Damage Range Expands - (Christian Krupke and John Obermeyer)

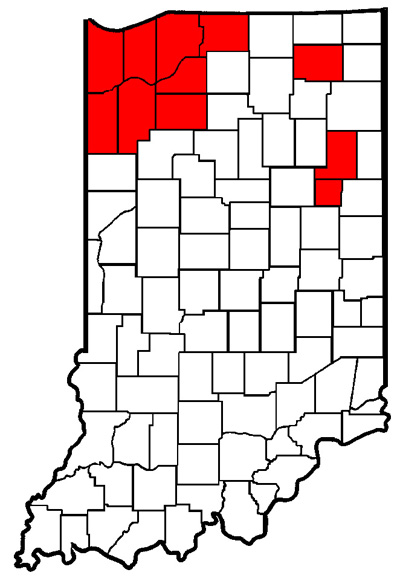

We appreciate the efforts of many of you that are helping to monitor corn for western bean cutworm (WBC) damage and notify us of counties not previously infested. The following map shows the known distribution of larvae and damage so far in 2009. Please let us know if you find an infestation in a county not yet identified.

It is likely that damaged ears will be noticed near, or at, the time of harvest by producers. At that time, with worms absent, it cannot be certain that other worm feeders, e.g., corn earworm, fall armyworm, didn’t cause that damage. Therefore, our time for confirming WBC damage is soon ending, as mature larvae drop from the plant and burrow into the soil for overwintering. Remember: the damage alone is NOT diagnostic and infestations are extremely patchy so a good subsampling of different field areas is essential.

By far, the highest, and most severe infestations of WBC have been in sandier soil areas. However, this past week we have been made of aware of fields with silty-loam soils also with significant infestations. Next summer’s moth flight numbers may help us ascertain whether larvae in these heavier soils were able to successfully overwinter. If you are interested in tracking this moth next summer with a pheromone trap, please let us know.

Known counties with WBC infestations

![]()

Aphid Update - (Christian Krupke and John Obermeyer)

SOYBEAN: As many soybeans throughout the state enter the R6 growth stage, the danger period is all but over for soybean aphid in those mature fields. This is a good opportunity to review the “aphid year”: We saw many aphids going into overwintering late in 2008. This led us to believe we may be in for a big year this year in terms of outbreaks on soybeans. This did not materialize. While we had a few fields over threshold in the northwestern corner of the state and in some isolated southern pockets, the majority of Indiana soybean growers would have been hard-pressed to find a single aphid in their fields this season. The one notable exception is the southwest and south central areas (Vincennes, Terre Haute areas of the state, where there are some very late beans (currently R4) – these areas are seeing some late, high aphid numbers. This is fairly surprising due to the location – in past years we have not seen this area be a hotbed of aphid activity. But this is anything but a typical year.

We will keep you updated on the numbers of aphids we capture in suction traps this fall – in the past (though not this year), these have been good indicators of infestation levels the following growing season.

CORN: As seen in 2007, noticeable populations of several populations of aphids are being reported in corn. Two common cereal aphids (frequent pests of wheat), bird cherry-oat and English grain aphid, are often found colonizing plants. This is especially noticeable this season as more pest managers are out looking for western bean cutworm. Because most corn is in the late-dough to dent stage of growth, and moisture is not a limiting factor, we are generally not concerned about their impact on yield. They are not robbing the plant of much and not vectoring any diseases of consequence at this point. Our main question is why they are there. Initially when this was noticed there seemed to be a strong correlation of fields infested to those receiving a fungicide/insecticide aerial application. This would suggest that natural enemies (insects and pathogens) of the aphid were eliminated to some extent by the chemical applications, allowing the aphids to flourish. However, with this year’s dramatic decrease in foliar pesticide applications, this theory is weakened. Maybe it is nothing more than a symptom of late, well-hydrated corn providing a growth opportunity for these aphids – in most years the corn would not be this nutritious in early September.

Aphid colonization in ear zone

Both English grain (lifhter) and bird cherry-oat (darker) aphids on corn leaf

![]()

Click here to view the Black Light Trap Catch Report

Cool Days, Cold Nights, Slow Corn, What’s Next? - (Bob Nielsen)

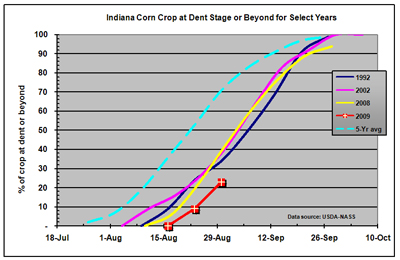

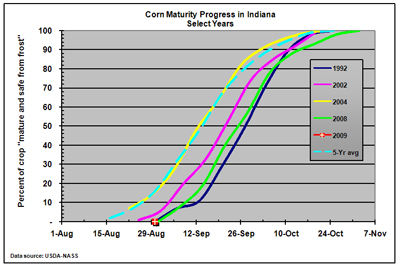

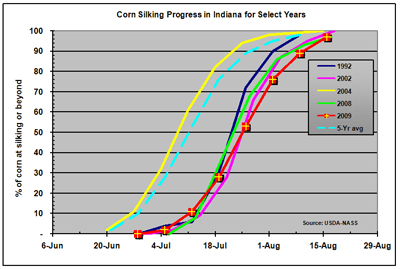

The good news is that most of Indiana’s late-planted corn crop escaped serious heat or drought stress during the critical pollination period and, to date, much of the important grain filling period. The discouraging news is that the unusually cool 2009 growing season continues to put the brakes on the development of the crop. According to the most recent weekly USDA crop progress report, the majority of the state’s crop has progressed through the dough stage of development (R4) and is moving toward the dent stage (R5), but now lags nearly 3 weeks behind the 5-year average progress (Fig. 1). If the current rate of crop progress continues for the remainder of the season, quite a bit of the state’s crop will mature in October rather than September (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Corn denting progress in Indiana for select years.

Fig. 2. Corn maturity progress in Indiana for select years.

Recent night-time low temperatures in the low to mid-40’s°F have certainly increased growers’ concerns about the prospects for successfully maturing this crop and whether these unusually cool temperatures will impact grain yield. Unfortunately, the effects of such an unusually cool grain filling period on corn maturity dates and yield in the central Corn Belt are not well known, partly because the historical occurrence of such unusually cool grain filling periods is so infrequent.

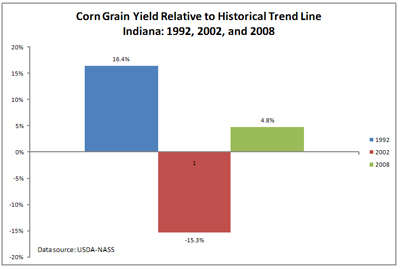

In an earlier article I referenced the similarity between this season’s slow pace of crop development with three earlier years of 1992, 2002, and 2008 (Fig’s 1 and 2). Though crop progress in those three growing seasons were similarly delayed, the end result for grain yields varied dramatically (Fig. 3). In my judgement, the 2009 growing season is more similar to the 1992 and 2008 growing seasons than to the disastrous 2002 growing season. Drought stress accompanied the delayed crop development in 2002 and contributed strongly to the large decrease from trend yield that year. Indiana’s corn crop has not experienced such widespread drought stress in 2009. The USDA-NASS certainly believes that yields will be good this year, according to their first yield estimate released 12 Aug that pegs Indiana’s 2009 corn crop at 163 bu/ac or 5.6% above trend yield.

Fig. 3. Corn grain yield relative to historical trend line for Indiana in 1992, 2002, and 2008.

Nevertheless, the recent weeks of cool weather accentuated with the recent nights of temperatures in the low to mid-40’s°F have fueled vigorous debates amongst the regulars down at the Chat ‘n Chew Cafe about how the crop will respond. Moderate temperatures and adequate moisture during the grain fill period are generally favorable for kernel set success and kernel weight development. However, it is true that temperatures as low as 50°F or lower can be detrimental to the photosynthetic processes. Canadian researchers Ying et. al., (2000) documented that photosynthetic rates in corn decreased by 18 to 30% the day following a cold temperature stress of about 40°F during grain filling. The more important question is whether multiple days of cold temperature stress during grain filling can cause longer-term reductions in photosynthetic rates that may actually lead to a premature senescence and development of kernel black layer. There is limited research that addresses this question.

Observations over the years, though, lead me to believe that there comes a point late in grain fill where extended periods of cool temperatures cause the plant to slowly shut down even though no actual frost injury has occurred. These observations are in agreement with those of Daynard (1972) who suggested that extended periods of cool temperatures, not frost, were a more probably cause of what he characterized as “premature” black layer development. He noted that kernel black formation occurred shortly after cold spells when the average daily MAXIMUM temperatures were 54°F or cooler. The good news, to date, is that we have yet to experience such low daily MAXIMUM temperatures.

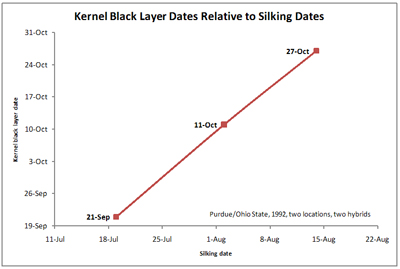

Our own research from 1992 offers us a hint of what to expect on the calendar timing of kernel black layer formation (i.e., physiological maturity) relative to the silking date (Fig. 4). The data shown in Fig. 4 are from two adapted hybrids grown at two locations (westcentral IN and southwest OH) in 1992 and represent a subset of data collected from 1991 through 1994 in our studies on the effect of delayed planting on thermal requirements of corn (Nielsen et. al., 2002).

Fig. 4. Kernel black layer dates vs. silking dates for two hybrids at two locations in 1992. Collaborative research between Purdue/Ohio State.

For planting dates where silking occurred towards late July, kernel black layer formation occurred by 21 September. Where silking occurred in early August, kernel black layer occurred by 11 October. Where silking occurred about mid-August, kernel black layer formation occurred by 27 October, but occurred 10 to 14 days AFTER a killing freeze event. All of the earlier silking dates (late July and early August) successfully reached kernel black layer prior to a killing freeze. Given the similarities between 1992 and 2009, I suggest that these data represent something of a crystal ball for us to gaze into for this year’s crop.

So, what can we say about the fall freeze risk to this year’s crop? We know that USDA-NASS estimated that 76% of Indiana’s corn crop had silked by 2 Aug (Fig. 5). Our previous research suggests that most of that should black layer no later than early October. Another 13% of the crop had silked by 9 Aug and that may black layer by approximately 11 Oct. Much of the remainder of the state’s crop (8 to 11%) had silked by 16 Aug or later. That portion of the crop may not mature until late October to early November AND will likely experience a killing fall freeze PRIOR to normal kernel black layer formation. Assuming that the tail end of this year’s crop will at least make it to the half-milkline stage of development prior to a killing freeze, the potential yield loss for an individual field due to premature plant death would be no more than 12% (Afuakwa & Crookston, 1984).

Fig. 5. Corn silking progress in Indiana for select years.

Related References

Afuakwa, J. J. and R. K Crookston. 1984. Using the kernel milk line to visually monitor grain maturity in maize. Crop Sci. 24:687-691.

Daynard, T.B. 1972. Relationships among black layer formation, grain moisture percentage, and heat unit accumulation in corn. Agron. J. 64:716-719.

Nielsen, R.L. (Bob). 2008. Grain Fill Stages in Corn. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. [online] <http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/GrainFill.html> [URL accessed 8/31/09].

Nielsen, R.L. (Bob). 2009. A Tale of Three Cropping Seasons. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. [online] <http://www.kingcorn.org/news/articles.09/CropProgress-0803.html> [URL accessed 9/1/09].

Nielsen, R.L. (Bob). 2009. Effects of Stress During Grain Filling in Corn. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. [online] <http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/GrainFillStress.html> [URL accessed 9/1/09].

Nielsen, R.L., P.R. Thomison, G.A. Brown, A.L. Halter, J. Wells, & K.L. Wuethrich. 2002. Delayed Planting Effects on Flowering and Grain Maturation of Dent Corn. Agron. J. 94:549-558.

USDA-NASS. 2009. Crop Production. USDA National Ag. Statistics Service. [online] <http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/usda/nass/CropProd//2000s/2009/CropProd-08-12-2009.pdf> [URL accessed 9/1/09].

USDA-NASS. 2009. Crop Progress. USDA National Ag. Statistics Service. [online] <http://usda.mannlib.cornell.edu/MannUsda/viewDocumentInfo.do?documentID=1048> [URL accessed 8/31/09].

Ying, J., E.A. Lee, and M. Tollenaar. 2000. Response of maize leaf photosynthesis to low temperature during the grain-filling period. Field Crops Research 68:87-96.

![]()

Bug Scout

I don't think the delayed corn maturity is going to slow him down!