Pest & Crop Newsletter, Entomology Extension, Purdue University

- Winter Conditions and Insect Survival

- Comparison of Rootworm Product Performance Under Low to High Pressure

- Rootworm Insecticide Classification and Consistency of Performance

Winter Conditions and Insect Survival – (John Obermeyer, Christian Krupke, and Larry Bledsoe)

- Temperature is just one factor that impacts an insect’s winter survival

- Temperatures and moisture influenceinsect numbers and subsequent crop damage

- Production practices, such as date of planting, tillage type, and herbicide application, have a large influence on pupulations as well

We have all heard a great deal about global warming in the past few months. While there is little doubt that this phenomenon is occurring, it may not have seemed like it over the last few months in Indiana. For example, the past winter has given us extremes in both temperatures and forms of precipitation. While the days of late December were atypically warm, the month of February brought us a prolonged cold spell. What will this mean for insects and and subsequent crop damage this coming season? As you probably already guessed…it depends on the insect. The following information on insect, environment, crop interactions might clear the picture somewhat.

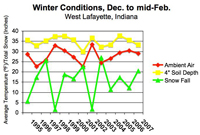

Overwintering insects utilize various behavioral and physiological mechanisms to keep them from dying during the long winter months. Survival tactics include, but are not limited to: lowering metabolic rates, freeze resistant body fluids, reducing water content in essential tissues, and finding protected microenvironments. Predictive models for some overwintering insects exist, but it is impossible to measure all of the environmental variables that individual insects experience in their overwintering locations. The graph above compares ambient air and 4”soil depth temperatures with snowfall recorded at the Agronomy Center for Research and Education in West Lafayette for twelve winters. This depicts how soil temperatures tend to follow air temperature trends. However, as snowfall amounts decrease, the temperature differential is less between the air and soil (e.g., 2002, 1998). It comes as no surprise that snow cover provides an insulating blanket for overwintering insects at or below ground level. Though the differences may seem minor to us, to a small, cold-blooded insect, it may make the difference between life and death.

Overwintering insects utilize various behavioral and physiological mechanisms to keep them from dying during the long winter months. Survival tactics include, but are not limited to: lowering metabolic rates, freeze resistant body fluids, reducing water content in essential tissues, and finding protected microenvironments. Predictive models for some overwintering insects exist, but it is impossible to measure all of the environmental variables that individual insects experience in their overwintering locations. The graph above compares ambient air and 4”soil depth temperatures with snowfall recorded at the Agronomy Center for Research and Education in West Lafayette for twelve winters. This depicts how soil temperatures tend to follow air temperature trends. However, as snowfall amounts decrease, the temperature differential is less between the air and soil (e.g., 2002, 1998). It comes as no surprise that snow cover provides an insulating blanket for overwintering insects at or below ground level. Though the differences may seem minor to us, to a small, cold-blooded insect, it may make the difference between life and death.

One common misconception is that a single “hard freeze” will wipe out many of the insects or eggs during the winter season. In fact, it often takes much more than this to make a difference to insect populations. For example, our key corn pest, the western corn rootworm, which overwinters in the egg stage, requires a total of 35 days at or below 14ºF for large-scale egg mortality to occur. In Indiana, we did not see anywhere near these accumulations of cold. Other insects are not quite this hardy, but the point here is that a single cold event can often be survivable for most of our key pests.

Above Ground Insects:

Corn Flea Beetle

Overwintering stage – adults in grassy areas or woodlots

Crop damage increases with early planted/emerging corn. Early in the spring, beetles will feed on grasses. Corn flea beetles will then colonize the earliest emerging corn. Some corn hybrids and inbreds are more susceptible than others to their foliar feeding damage.

Concerns – besides the potential for reduced stands from damage to emerging seedlings, this beetle is a vector of Stewart’s disease. Stewart’s disease is a greater threat to certain inbred lines of corn, some pop/sweet corn varieties, but rarely a concern in yellow dent corn. To estimate the potential severity of Stewart’s disease, add the average daily temperatures for the months of December, January, and February. If the sum is below 90, the potential for disease problems to develop is low. If between 90 and 100, moderate disease activity is a possibility. Sums above 100 indicate a high probability that severe problems will develop for susceptible corn. Look for this information in the next Pest&Crop issue.

European Corn Borer

Overwintering stage – larvae in corn stalks and stalks of weed residue

Crop damage increases due to first generation corn borer with – early planting and the tallest corn within an area, usually around the first week of June.

Concerns – high yielding/fast growing hybrids (“race horse”) planted early in highly productive soils are often targeted by first generation egg-laying moths.

Considerations – Overall 2006 populations going into overwintering sites were relatively low. A mild, moist spring may encourage corn borer pathogens that could drastically reduce numbers of overwintering larvae. Rainy, stormy weather during the mating and egg-laying period is detrimental to the moths. Second generation corn borer will typically cause the most damage, this has very little to do with the overwintering larvae but more to do with late-season growing conditions and availability of late-planted or late-maturing corn.

Soybean Aphid

Overwintering stage – eggs on buckthorn plant

Crop damage occurs when massive flights of winged aphids, from areas of high density, colonize soybean plants in the reproductive growth stages (usually R2/R3 in Indiana). This occurred in late July and early August in 2003 and 2005 causing soybean yield losses mostly in northern Indiana counties.

Concerns – unprecedented numbers of winged aphids were captured in suction traps and seen this fall on buckthorn plants in northern Indiana. These captures were the highest of all the Midwestern state suction trap network (40 traps, primarily in IL, IA, WI, MN and MI). Past history (since year 2000) indicates that significant in-season infestations/outbreaks follow high aphid activity in the previous fall – this does not bode well for Indiana soybean growers and early indications are that this will be an “aphid year”, and perhaps an early aphid year by Indiana standards.

Considerations – Buckthorn (Rhamnus spp.), the soybean aphid’s overwintering host, exists in scattered and very localized locations in the state, and is more common around the Great Lakes region. It is unknown whether such low densities of buckthorn can sustain significant aphid populations before soybean are planted and growing in the spring. Aphid predators, e.g., lady beetles, pirate bugs, lacewings, etc., made a sudden resurgence in populations in the fall of 2006 and eliminated some populations of winged aphids and eggs.

Black Cutworm

Overwintering stage – doesn’t overwinter in the Midwest

Crop damage increases with large moth flights into Indiana. Moths are carried into the state on storm fronts from the southwestern United States and Mexico.

Concerns – Control early-season weeds! Winter annuals growing on agricultural lands are targeted egg laying sites for arriving female moths. Burn-down herbicides applied during or shortly after planting will force hatching black cutworm larvae to move from the dying weeds to emerging crops.

Considerations – a hard freeze after most egg laying has occurred in late April may reduce black cutworm survivorship. Timing and number of moths arriving into the state is variable from year to year. Clean fields are less likely to have problems. Early planting followed by favorable growing conditions during seedling establishment may allow corn to quickly reach a size that is resistant to feeding injury.

Below Ground Insects:

Western Corn Rootworm

Overwintering stage – eggs in the soil (from just below the soil surface to a depth of 12-15”)

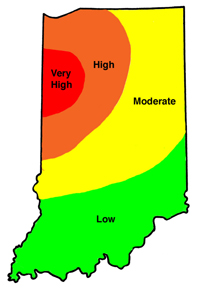

Crop damage risk increases where rootworm beetles laid numerous eggs in previous year’s corn, soybean, or alfalfa crop and the field will be planted to corn in 2007 (see map below for areas where first-year corn risk is highest).

Concerns – Western corn rootworm beetles were observed frequently in soybean fields last summer in northwest and west central counties.

Considerations – soil insecticides applied duringvery early corn planting may have reduced efficacy by the time the rootworm eggs hatch in late May to early June. Cold winter temperatures have little effect on rootworm egg survival.

White Grubs

Overwintering stage – larvae/grubs in the soil

Crop damage increases withearly planting. Delayed crop emergence and growth will increase the opportunity for grubs to come into contact with and feed-on seedling roots.

Concerns – Japanese beetle is the predominant grub species in cultivated cropland in Indiana. Areas that experienced high numbers of Japanese beetles last year potentially have a higher risk of grub damage this spring.

Considerations – beetle numbers were relatively low last year. High organic matter soils may sustain large grub populations without significant crop damage since grubs can feed on dead and/or decaying plant matter.

![]()

Comparison of Rootworm Product Performance Under Low to High Pressure -(John Obermeyer, Christian Krupke, and Larry Bledsoe)

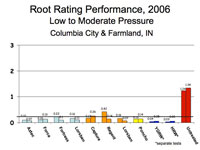

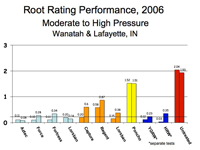

The following bar charts help compare the efficacy of rootworm control products by application methods (granular, liquid, seed-applied, and Bt) under varying rootworm pressure. Refer to the previous “Perceived First-Year Corn Rootworm Risk Area” map. Farms in the low to moderate risk areas may experience the pressure associated with the first chart. Those located in the higher risk areas are more likely to see greater rootworm pressure as depicted in the second graph.

The left side of the graphs represents the Node Injury Scale 0-3, where 0 indicates little to no rootworm feeding, and a value of 3 indicates few roots remaining. Damage greater than 0.25 (one-quarter of 1 node of roots, indicated by horizontal black line across graph) indicates where yield losses may begin to occur. However, bear in mind that the relationship between damage and yield when roots are evaluated (late July) is often not strong. The amount and distribution of rainfall throughout the remaining months of ear development will have a large effect on yield. Use the charts below to tell you how well the different products hold up to rootworm pressure, bearing mind the amount of risk you will accept. Do not use the charts as a direct predictor of yield protection.

![]()

Rootworm Insecticide Classifications and Consistency of Performance - (John Obermeyer, Christian Krupke, and Larry Bledsoe)

- The following table lists registered rootworm soil insecticides by chemical class

- Follow label uses and restrictions

- Many factors should be considered before selecting a product

Spring Weed Control in Winter Wheat – (Bill Johnson and Glenn Nice)

Unlike just a few years ago when there were only a handful of herbicides registered for the control of grasses and broadleaf weeds in winter wheat grown in Indiana, there are now a number of herbicides available to control weeds in wheat. The most common broadleaf or perennial weed problems we run into at this time of year in Indiana wheat include chickweed, deadnettle, henbit, dandelion, mustards, field pennycress, shepherdspurse, Canada thistle, and wild garlic. The most common grass problems are annual bluegrass, annual ryegrass, cheat, and downy brome. Some of the commonly used herbicides, rates, their application timings, and weeds controlled are listed in the table below.

It is also important to be aware that restrictions exist concerning application timing of these herbicides to avoid crop injury. Phenoxy herbicides, such as 2,4-D and MCPA, control a number of annual broadleaf weeds and are the least expensive of these herbicides to use. However, proper application timing of the growth-regulating herbicides 2,4-D, MCPA and Banvel is critical to avoid crop injury and possible yield losses. These herbicides can cause substantial crop injury and yield loss in small grains if applied before tillering begins or after development of the grain heads have been initiated.

The exact time at which grain heads have been initiated is not easy to determine, but this event always just precedes stem elongation. The occurrence of stem elongation can be easily detected by the appearance of the first node or “joint” above the soil surface, commonly referred to as the “jointing stage.” Pinch a wheat plant stem at the base between the thumb and forefinger and slide your fingers up the stem. The presence of a node or joint will be felt as a hard bump about an inch above the soil surface. Slicing the stem lengthwise with a sharp knife will reveal a cross section of the hollow stem and solid node. If jointing has occurred, applications of 2,4-D, MCPA and Banvel should be avoided because crop injury and yield loss are likely. Research from the University of Missouri Weed Science program has shown a 3- to 6-bushel per acre yield loss from 2,4-D and Banvel applications to wheat after the jointing stage.

MCPA alone at labeled rates should be applied before jointing. However, the amount of MCPA applied in Bronate, a combination of bromoxynil and MCPA, is low enough to permit later applications.

Many wheat fields in Indiana contain wild garlic and wild onion. Although not considered as strong competitors with a wheat crop, wild garlic (Allium vineale) and wild onion (Allium canadense) are both responsible for imparting a strong odor to beef and dairy products. Wheat producers and grain elevator operators are very familiar with dockages that occur with the presence of wild garlic or onion bulbs in their harvested grain. Found throughout Missouri, wild garlic is a native of Europe, while wild onion is native. Despite the fact that these perennials both occur in similar habitats, wild garlic occupies the majority of small grain settings, including wheat.

Control measures for wild onion and wild garlic will differ. Producers, consultants and industry personnel will want to make certain that they are able to distinguish between these two weed species. The vegetative leaves of wild garlic are linear, smooth, round and hollow flowering stems are solid). A major difference with wild onion is that its leaves are flat in cross section and not hollow. Another varying feature are the underground bulbs. Wild garlic’s bulbs have a thin membranous outer coating while wild onion’s bulbs have a fibrous, net-veined coating.

Harmony Extra (thifensulfuron + tribenuron) is the herbicide most commonly used for control of garlic in wheat, plus it controls a relatively wide spectrum of other broadleaf weeds and possesses a fairly wide application window. Harmony GT (thifensulfuron) also has activity on wild garlic, but is considered to be slightly weaker than Harmony Extra. Peak is also labeled and effective on wild garlic in wheat, but it is fairly persistent in soil. The Peak label does not allow one to plant double crop soybean following wheat harvest in Indiana. Wild onion is controlled with 2,4-D. Keep in mind that both of these weeds are perennials and the full labeled rate is needed for adequate control.

Over the last couple of years, dandelion infestations in wheat have increased dramatically, particularly in the eastern part of Indiana. The best dandelion control is usually obtained with fall applications of glyphosate before wheat is planted. So keep this in mind for fields that will be planted to wheat in coming fall. For this spring, the best approach to dandelion management in wheat will be the higher rates of 2,4-D, Stinger, or Curtail. Stinger will have the widest application window and can be applied up until the boot stage.

Finally, we now have a couple of grass herbicides labeled for use in Indiana wheat, Axial and Osprey. Osprey controls annual bluegrass and annual ryegrass; while Axial will control ryegrass, foxtails, and barnyardgrass.

Table 1. Herbicides to control broadleaf weeds in winter wheat |

||||

Active Ingredient |

Trade name(s) |

Rate Per Acre |

Application Timing |

Weeds Controlled |

2,4-D |

Weedar, Weedone, Formula 40, others |

1 to 2 pts |

Tillering to before jointing |

Field pennycress, shepherdspurse, wild mustard, ragweeds, lambsquarter, horseweed (marestail), prickly lettuce, wild onion |

Bromoxynil |

Buctril, Moxy |

1.5 to 2 pts |

Emergence to boot stage |

Wild buckwheat, common ragweed, lambsquarter, field pennycress, henbit, shepherdspurse, wild mustard |

Bromoxynil + MCPA |

Bronate, Bison |

1 to 2 pts |

After 3-leaf stage but before wheat reaches boot stage |

Same as bromoxynil and MCPA |

Carfentrazone |

Aim |

0.33 to 0.66 oz |

Before jointing |

Catchweed bedstraw, lambsquarter, field pennycress, tansy mustard, flixweed |

Clopyalid |

Stinger |

0.25 to 0.33 pts |

After 2-leaf stage until boot stage |

Wild buckwheat, marestail, dandelion, Canada thistle |

Clopyralid + 2,4-D |

Curtail |

1 to 2.67 pts |

Tillering to jointing |

Wild buckwheat, wild lettuce, mustards, field pennycress, shepherdspurse, lambsquarter, ragweeds dandelion, Canada thistle |

Clopyralid + fluroxypyr |

WideMatch |

1 to 1.33 pts |

After 2-leaf stage until boot stage |

Wild buckwheat, marestail, ragweeds, dandelion, Canada thistle |

Dicamba |

Banvel |

0.125 to 0.25 pt |

Emergence to before jointing |

Field pennycress, wild buckwheat, ragweeds, kochia, lambsquarter, horseweed (marestail), prickly lettuce, shepherdspurse |

Fluroxypyr |

Starane |

0.5 to 0.6 pt |

From 2-leaf up to and including flag leaf emergence |

Hemp dogbane, common and giant ragweed |

MCPA |

Chiptox, Rhomene, Rhonox |

1 to 4 pts |

Tillering to before jointing |

Field pennycress, shepherdspurse, wild mustard, ragweeds, lambsquarter, horseweed (marestail), prickly lettuce, wild buckwheat |

Mesosulfuron- methyl + safener |

Osprey |

4.75 oz |

After emergence or spring before jointing |

Annual bluegrass and annual ryegrass |

Pinoxaden |

Axial |

8.2 oz |

2-leaf to pre-boot stage |

Ryegrass, foxtails, and barnyardgrass |

Prosulfuron |

Peak |

0.5 oz |

Emergence to second node visible |

Mustards, field pennycress, garlic |

Thifensulfuron |

Harmony GT |

0.3 to 0.6 oz |

After 2-leaf stage but before flag leaf becomes visible |

Wild garlic, field pennycress, wild mustard, chickweed, henbit, shepherdspurse, wild mustard, lambsquarter |

Thifensulfuron + tribenuron |

Harmony Extra |

0.3 to 0.6 oz |

After 2-leaf stage but before flag leaf becomes visible |

Wild garlic, field pennycress, wild mustard, chickweed, henbit, prickly lettuce, shepherdspurse, wild mustard, lambsquarter |

Tibenuron |

Express |

1/6 to 1/3 oz |

After 2-leaf stage but before flag leaf becomes visible |

Chickweed, deadnettle, henbit, wild lettuce, mustards, field pennycress, lambsquarter |

Wet Fall Leads To Spring Tillage Dilemmas - (Tony Vyn and Jenn Stewart, News and Special Projects Writer)

The seemingly endless rain of fall 2006 continues to impact Midwestern farmers as they begin looking ahead to the 2007 spring planting season. Because wet weather delayed last season’s harvest, corn and soybean producers had to scramble through soggy fields to harvest their crops before it was too late. This gave farmers little choice, but to forego some, if not all, of their fall tillage operations. “It certainly was an incredibly wet fall and that prevented many of the planned tillage operations from being done,” said Tony Vyn, Purdue University tillage Extension specialist. “That means that as we go into this spring there are a few options.”

Based on the shape that fields are in and what was accomplished last fall, farmers will need to decide what crops will best suit their needs and what tillage practices will prove most beneficial. “Probably the easiest scenario is when corn is intended to be planted following soybeans,” Vyn said. “This represents a really excellent opportunity to consider no-till rather than doing any tillage at all.” However, there may be situations where a farmer is really insistent on doing some tillage where corn will be planted on soybean stubble, Vyn said. In those situations, he recommends a strip tillage operation. “If there is an opportunity to do strip tillage three or four weeks ahead of planting, then that operation should be done to shallow depths, no deeper than 5 to 6 inches, and should be done with the intent to have a berm that’s really finely aggregated and that will allow for faster warming and drying so that planting may proceed on a more timely basis,” Vyn said. “Another option that exists is fluffing harrows, or something that operates very shallowly simply to loosen up the residue that may have been matted down by all of the excessive rain that we’ve had since harvest.

With the ethanol boom taking place, crop forecasts indicate that corn will not only follow soybeans, but there will be more corn on corn grown in the upcoming year. “In a sense, we don’t go into that situation with a particularly well-prepared situation because usually corn after corn requires more tillage, especially on fine-textured soils that are poorly drained,” Vyn said. Under these conditions Vyn recommends planting no-till corn after corn on light, well-drained soils, 6 to 7 inches away from the old corn rows. When doing this, Vyn said he is very keen on applying at least 30 pounds per acre of nitrogen with the planter.

In a situation where a high-clay content soil is involved, a shallow tillage operation may be best, Vyn said. “When we have corn after corn on these more finely textured soils that are slow to dry out on the surface, we recommend a shallow combination of tillage tools that are operated when the soil conditions in the top 3 to 4 inches are fit for doing something,” he said. Regardless of which tillage operations are the best for each farmer, most have the same associated concerns. “There are always two primary concerns when we are talking about spring tillage,” Vyn said. “One is moisture management. It is very important to manage for achieving uniform moisture conditions in the seed row area. Secondly, it is all about compaction avoidance, because if we smear the soil or compact the soil excessively, we will be much more vulnerable to root restrictions – especially if the later spring weather turns hot and dry.”

Homegrown Indiana: A Local Foods Expo. Join others in these first time events aimed towards strengthening local foods networks. Food producers, growers, marketers, specialty retailers, chefs, food entrepreneurs and interested community members are all invited. The programs include workshops, presentations, and networking opportunities. Speakers include Lisa Johnson, Valley Food and Farm local foods project in Vermont and New Hampshire; Dr. Jennifer Dennis, Purdue University; Mari Coyne, Chicago’s Food Forager; and others. Registration is $15 per person in advance; exhibit and sponsorship opportunities are also available.

Northwest Indiana: March 13, 2007 9:00 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. Central Time. Porter Co. Expo Center, Valparaiso. For more information, see <www.ces.purdue.edu/porter/> or contact Kris Parker, 219-465-3555 ext. 27 or parkerkj@purdue.edu.

North Central Indiana: March 14, 2007 9;00 – 4:30 Eastern Time. Elkhart Co., 4-H Fairgrounds. For more information contact Jeff Burbrink at 574-533-0554 or jburbrink@purdue.edu

![]()

Tri-State Organic IP Video Program: Organic Weed Management.

March 15, 2007, 6:00 – 8:30 p.m. Eastern/5:00 – 7:30 p.m. Central.

Offered at 16 sites around Indiana and in neighboring states. Topics to be covered: Soil characteristics that influence weed management, Dr. Steve Weller, Purdue University; Cropping Practices that influence weed management, Dr. John Cardina, Ohio State University; Tools, practices, and materials for weed management in field crops and vegetables, Dr. John Masiunas, University of Illinois; Organic farmers’ weed management systems on vegetable and agronomic farms, Dale Rhoads, Brown Co., IN; John Simmons, LaPeer Co., MI, Dave Campbell, NE Illinois, Rex Spray, Mt. Vernon, OH.

Registration is $10 per person/farm and includes workshop materials and refreshments. Online registration will be available through the Purdue Conference Division by logging onto <https://www.conf.purdue.edu/>. For more information or assistance with registration, contact Liz Maynard at 219-785-5673 or 800-872-1231 ext 5673.

![]()

Managing Pests in Commercial Pumpkins and Melons. March 20, 2007, 1:00 – 4:00 p.m. Eastern Time. Fulton Co. 4-H Fairgrounds, Rochester. PARP credits available. For more information contact Mark Kepler at 574-223-3397.

![]()

Managing Soybean Aphids in 2007—How Will Biological Control Contribute? A distance education short course March 6, 2007, 8:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. (CDT)

Since its discovery in North America in 2000, the soybean aphid has become the key insect pest of soybean in the north central states and Canada. Widespread outbreaks in 2003 and 2005 cost soybean producers millions of dollars in management costs and lost yields. Captures of winged soybean aphids in suction traps in the Midwest in 2006 suggest the potential for a soybean aphid outbreak in 2007.

Natural enemies play a significant role in regulation of soybean aphid populations annually. The multicolored Asian lady beetle and the insidious flower bug are two of the mostly widely recognized predators of soybean aphids, but other predators, parasitoids, and pathogens can have significant impacts.

On March 6, 2006, entomologists from throughout the Midwest will present a short course focused on management of soybean aphids in 2007, with emphasis on biological control, including conservation of natural enemies. Experts from several states will deliver the short course via distance education technology to sites in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin. The general content of the program will be:

- History and biology of the soybean aphid

- Review of the soybean aphid situation

- Biological control of soybean aphids—What is it? What do we have to work with in the United States?

- Introducing new natural enemies into the U.S.

- Preparing for soybean aphids in 2007—Management guidelines, and the potential for biological control.

- Questions, answers, feedback

The short course will be conducted on March 6, 2007, from 9:30 p.m. to 1:00 noon (EST), with audience interaction and feedback from 12:00 noon to 12:30 p.m.

The short course is being developed for soybean producers, members of state soybean associations, agribusiness professionals (CCA CEUs will be applied for), Extension personnel, and any other interested groups. On-line registration: <http://www.ncipmc.org/teleconference/>. This short course is funded by the North Central Soybean Research Program (NCSRP).

![]()

PURDUE EXTENSION FIELD CROP SPECIALISTS

| Entomology: http://www.entm.purdue.edu/entomology/ext/index.htm | |||

| Steve Yaninek | (765) 494-4554 | yaninek@purdue.edu | Head, Dept. of Entomology |

| Larry Bledsoe | (765) 494-8324 | lbledsoe@purdue.edu | Field Crop Insects |

| Jamal Faghihi | (765) 494-5901 | jamal@purdue.edu | Nematology |

| Greg Hunt | (765) 494-4605 | hunt@purdue.edu | Beekeeping |

| Christian Krupke | (765) 494-4912 | ckrupke@purdue.edu | Field Crop Insects |

| Judy Loven | (765) 494-8721 | loven@purdue.edu | USDA, APHIS, Animal Damage |

| Linda J. Mason | (765) 494-4568 | lmason@purdue.edu | Food Pest Mgmt. & Stored Grain |

| John L. Obermeyer | (765) 494-4563 | obe@purdue.edu | Field Crop Insects & IPM Specialist |

| Tammy Luck | (765) 494-8761 |

luck@purdue.edu | Administrative Assistant |

| Agronomy: http://www.agry.purdue.edu/ext | |||

| Craig Beyrouty | (765) 494-4774 | beyrouty@purdue.edu | Head, Dept. of Agronomy |

| Sylvie Brouder | (765) 496-1489 | sbrouder@purdue.edu | Plant Nutrition, Soil Fertility, Water Quality |

| Jim Camberato | (765) 496-9338 | jcambera@purdue.edu | Soil Fertility |

| Shawn Conley | (765) 494-0895 | conleysp@purdue.edu | Soybeans, Small Grains, Specialty Crops |

| Corey Gerber | (765) 496-3755 | gerberc@purdue.edu | Director, Diagnostic Training Center |

| Brad Joern | (765) 494-9767 | bjoern@purdue.edu | Soil Fertility, Waste Mgmt. |

| Keith D. Johnson | (765) 494-4800 | johnsonk@purdue.edu | Forages |

| Charles Mansfield | (812) 888-4311 | cmansfie@purdue.edu | Small Grains, Soybean, Corn |

| Robert L. Nielsen | (765) 494-4802 | rnielsen@purdue.edu | Corn, Sorghum, Precision Agriculture |

| Gary Steinhardt | (765) 494-8063 | gsteinha@purdue.edu | Soil Mgmt., Tillage, Land Use |

| Tony Vyn | (765) 496-3757 | tvyn@purdue.edu | Soil Mgmt. & Tillage |

| Terry West | (765) 494-4799 | twest@purdue.edu | Soil Mgmt. & Tillage |

| Lisa Metts | (765) 494-4783 |

lmetts1@purdue.edu | Extension Secretary |

| Botany and Plant Pathology: http://www.btny.purdue.edu/Extension | |||

| Tom Bauman | (765) 494-4625 | tbauman@purdue.edu | Weed Science |

| William Johnson | (765) 494-4656 | wgj@purdue.edu | Weed Science |

| Glenn Nice | (765) 496-2121 | gnice@purdue.edu | Weed Science |

| Karen Rane | (765) 494-5821 | rane@purdue.edu | Plant & Pest Diagnostic Lab |

| Gail Ruhl | (765) 494-4641 | ruhlg@purdue.edu | Plant & Pest Diagnostic Lab |

| Greg Shaner | (765) 494-4651 | shanerg@purdue.edu | Diseases of Field Crops |

| Andreas Westphal | (765) 496-2170 | westphal@purdue.edu | Soil-borne Diseases |

| Fred Whitford | (765) 494-4566 | fwhitford@purdue.edu | Purdue Pesticide Programs |

| Charles Woloshuk | (765) 494-3450 | woloshuk@purdue.edu | Mycotoxins in Corn |

| Amy Deitrich | (765) 494-9871 FAX: (765)494-0363 |

amymd@purdue.edu | Extension Secretary |

| Agricultural & Biological Engr.: http://pasture.ecn.purdue.edu/ABE/Extension/ | |||

| Bernie Engel | (765) 494-1162 | engelb@purdue.edu | Interim Head, Dept. of Ag. & Bio. Engr. |

| Daniel Ess | (765) 496-3977 | ess@purdue.edu | Precision Ag., Ag System Mgmt. |

| Jane Frankenberger | (765) 494-1194 | frankenb@purdue.edu | GIS and Water Quality |

| Dirk Maier | (765) 494-1175 | maier@purdue.edu | Post Harvest Engineering |

| Mack Strickland | (765) 494-1222 | strick@purdue.edu | Precision Farming Appl. |

| Carol Glotzbach | (765) 494-1174 FAX: (765) 496-1356 |

glotzbac@purdue.edu | Extension Secretary |