Pest & Crop Newsletter, Entomology Extension, Purdue University

- What Do We Do About the Yellow Fields

- Cressleaf Groundsel and Indiana

- Herbicide Resistance Screening Available at Michigan State Universit Diagnostic Services.

Black Cutworm Damage Ahead of Schedule – (John Obermeyer, Christian Krupke, and Larry Bledsoe)

- Black cutworm damage is evident in cornfields in west central counties.

- Indiana pest managers should be looking for leaf feeding and initial cutting.

- Low rates of seed-applied insecticides are not protecting the plants.

- Management guidelines and rescue insecticides are given.

4th, 5th, and 3rd instar black cutworm larvae collected May 10, Tippecanoe County

Early Cutting from 4th black cutworm instar larva, May 10, Tippecanoe County

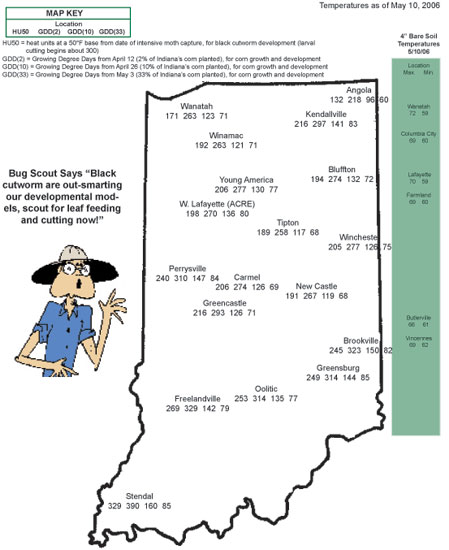

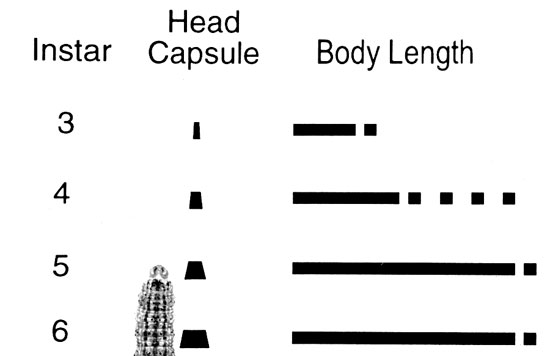

Fred Kramer, Pioneer Agronomist in WC Indiana, called early in the week to report some leaf-feeding and early cutting from black cutworm. Betsy Smith-Bower, Grower’s Co-op, also has found scattered black cutworm damage, with one field reaching treatment threshold. Because of the significant number of moths captured this spring, finding this damage is not a surprise. What is baffling us is how early in the season this damage is appearing. According to heat unit models, black cutworm development should only be to about a 3rd instar larva (about half-grown, and not large enough to cause this “cutting” damage), but stages of 3rd through 6th instar have been found this week.

Why we are finding such advanced larval development is not completely known. It is possible that moths arriving before our pheromone monitoring began in mid-March survived and successfully laid eggs in weedy fields. The underlying theme is that larger cutworms (up to 6th instar found) are cutting corn and smaller ones are feeding on the leaves. It is likely that a mix of cutworm sizes are present in fields, indicating that plant cutting percentages will only increase. Don’t be fooled by the minor leaf feeding that appears insignificant.

As we graphed last week in this newsletter, large numbers of black cutworm moths have been captured by our pheromone trap cooperators. This certainly set the stage for economic damage to Hoosier cornfields, although this is not a guarantee that damage will occur. Black cutworm moths are particularly fond of winter annuals, such as chickweed and various mustards, to lay eggs on. Fields that were showing lots of green a month or two ago are at highest risk for cutworm damage. This includes fields that were treated at planting with a soil and/or seed-applied insecticide. Remember, corn and soybean are not the preferred food of the black cutworm. It just so happens that it is normally the only plant remaining by the time larvae hatch and weeds have been killed. See the charts below for determining instars and making BCW management decisions.

| Black Cutworm Management Guidelines | ||||||

Avg. Instar of BCW |

# of Plant Leaves Fully Emerged |

|||||

6 or more |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|

4.0 |

1% + |

2% + |

2% + |

2% + |

3% + |

4% + |

5.0 |

2% + |

3% + |

4% + |

4% + |

6% + |

25% + |

6.0 |

4% + |

7% + |

9% + |

17% + |

Don't |

Don't |

7.0 |

6% + |

15% + |

50% + |

Don't |

Don't |

Don't |

- Look down the column at the left labeled “Average Instar of BCW” until you find the average instar of BCW found in the field. This column is called the Instar Row.

- Look across the top of the table and find the number that best represents the “Number of Plant Leaves Fully Emerged” for the plants inspected. A leaf is fully emerged if the leaf collar is visible. The column of figures below this is called the Leaf Column.

- Follow the Instar Row and the Leaf Column to the place where they intersect. This figure is the control threshold. If the percentage of cut or damaged plants in the field equals or exceeds this number, treatment may be advisable.

Insecticides Suggested for Foiar Application to Control Cutworms in Corn |

|

Material |

Amount Per Acre and Formulation* |

| bifenthrin (Capture) (1,2) | 2.1 - 6.4 fl. oz. EC |

| Chlorpyrifos (Lorsban) (1,2) | 1 - 2 pt. 4E |

| cyfluthrin (Baythroid 2) (1,2) | 0.8 - 1.6 fl. oz. E |

| deltamethrin (DECIS) (1,2) | 1.0 - 1.5 fl. oz. EC |

| esfenvalerate (Asana XL) (1,2) | 5.8 - 9.6 fl. oz. EC |

| gamma-cyhaothrin (Proaxis) (1,2) | 1.9 - 3.2 fl. oz. EC |

| lambda-cyhalothrin (Warrior) (1,2) | 1.92 - 3.20 fl. oz. CS |

| methyl parathion (Penncap-M) (1,2) | 4 pt. FM |

| permethrin (Ambush) (1,2) (Pounce) (1,2) |

6.4 - 12.8 fl. oz. EC 4 - 8 fl. oz. 3.2EC |

| zeta-cypermethrin (Mustang Max) (1,2) | 1.3 - 2.8 fl. oz. EW |

* Under dry conditions, where rotary hoeing may be needed to increase cutworm control, use the higher insecticide rate. |

|

![]()

Armyworm, It's Now or Never - (John Obermeyer Christian Krupke, and Larry Bledsoe)

- Moths lay eggs on grazzy crops and weeds.

- Corn can be quickly consumed when grass cover crop is burned down.

- Wheat dfoliation and head clipping can result.

- Fescue pastures can be denuded in days.

As previously reported, Kentucky has captured impressive moth numbers in their pheromone traps. Moths prefer to lay their eggs on dense grassy vegetation (e.g., wheat, grass hay, and grass cover crops). Initially, tiny larvae and their damage are hard to find. Larval development, especially in southern counties, should now have advanced to the point that high-risk crops can be assessed for feeding damage. To date, no reports of economic damage have been received; indicating infestations may be typically spotty rather than widespread as in 2001.

Early feeding: armyworm upper leaves, corn flea beetle lower leaves

Young armyworm, May 9, Tippecanoe County

Corn - Corn that has been no-tilled into or growing adjacent to a grass cover crop (especially rye) should be inspected immediately for armyworm feeding. Hatched larvae will move from the dying grasses to emerging/emerged corn. Armyworm feeding gives corn a ragged appearance, with feeding extending from the leaf margin toward the midrib. Damage may be so extensive that most of the plant, with the exception of the midrib and stalk, is consumed. A highly damaged plant may recover if the growing point has not been destroyed. If more than 50% of the plants show armyworm feeding and live larvae less than 1-1/4 inches long are numerous in the field, a control may be necessary. Larvae greater than 1-1/4 inches consume a large amount of leaf tissue and are more difficult to control. If armyworm are detected migrating from border areas or waterways within fields, spot treatments in these areas are possible if the problem is identified early enough.

Wheat & Grass Pasture - Examine plants in different areas of a field, especially where plant growth is dense. Look for flag leaf feeding, clipped heads, and armyworm droppings on the ground. Shake the plants and count the number of armyworm larvae on the ground and under plant debris. On sunny days, the armyworm will take shelter under crop residue or soil clods. If counts average approximately 5 or more per linear foot of row, the worms are less than 1-1/4 inches long, and leaf feeding is evident, control may be justified. If a significant number of these larvae are present and they are destroying the leaves or the heads, treat immediately.

![]()

This will be our last week for the black cutworm pheromone trap report.

Thanks to the many, dutiful cooperators!

![]()

What Do We Do About the Yellow Fields? – (Bill Johnson and Glenn Nice)

There are a lot of yellow fields out there, especially in the southern half of Indiana. The weed species is cressleaf groundsel, aka, ragwort, senecio, “that mustard thing.” See a related article for more information on the biology and identification of this weed.

Glenn and I have received a number of questions about control of this weed this past week because the recent wet spell did not allow burndown applications to be made in a timely manner during late April. Now we have fields with groundsel, plus chickweed, henbit, deadnettle, and winter annual grass in the seed set stage, and summer annuals that have started to emerge such as giant foxtail, giant ragweed, common lambsquarters, black nightshade, pigweeds and waterhemp and bolting horseweed (marestail) that emerged in the fall and seedling horseweed that emerged this spring. So what do we do? There are a couple of different herbicide programs to consider. In all cases, it is going to be best to add some 2,4-D to the mix to improve control of groundsel, bolting horseweed, and the summer annual broadleaf weeds. The chickweed and other winter annuals won’t be controlled well by anything since they are in the seed set stage, but they could be dessicated more rapidly if a paraquat-based program is used. Control of groundsel will also be a challenge since it is large, flowering and many of the lower leaves have fallen off of the plant, so herbicide uptake is limited by lack of leaf area.

Key Considerations. If flowering groundsel is the primary target, you can use glyphosate + 2,4-D or 2,4-D + paraquat + Sencor (beans) or atrazine (corn) if you desire more rapid dessication of weed biomass. In the glyphosate-based program, use the 1.5 lb ae/A rate with 1 pt/A of 2,4-D. Most labels require you to wait 7 days before planting corn or soybean with this rate of 2,4-D. In the paraquat-based program, use the upper end of the rate range for more effective control of large weeds. In our research, these programs have usually provided about 85 to 90% control of large, flowering groundsel. However, if the weather stays cool and wet, expect some regrowth of groundsel with either herbicide program that can be cleaned up with various postemergence treatments in corn or soybean.

How to Prevent this from Happening Next Year. This situation is a good educational opportunity to see the value of fall applied herbicides for managing groundsel. Groundsel is primarily a winter annual and fall applied treatments containing glyhposate and/or 2,4-D are very effective in reducing infestations. In Figure 2 (taken May 6, 2006) at the Southeast Purdue Ag Center, the field on the left was sprayed with glyphosate in the fall, the field on the right was not treated. Although we do not have 100% control of all weeds on this date, the field on the left is noticeably drier and will be planted 1-3 days earlier that the field on the right. Our recommendations would be to start with a clean field in both cases, so the weeds present in both fields should be controlled before planting with tillage or a burndown herbicide. If no-till practices are used, the field on the left could be managed effectively with the 0.75 lb ae/A rate of glyphosate alone. Because the field is in southeast Indiana and glyphosate-resistant horseweed is widespread in this area, so, we would also recommend using 2,4-D with glyphosate or a paraquat-based program with 2,4-D and a triazine. A low rate of paraquat could be used in this field compared to the field on the right. For the field on the right, we would recommend using a 1.5 lb ae/A rate of glyphosate with 2,4-D or a paraquat-based program mentioned above. The paraquat rate would need to be towards the upper end of the labeled rate range. If conventional-till practices are used, the field on the left will likely require at least 1 less field preparation pass with a field cultivator than the field on the right. (Figure 3 and Figure 4) The field on the right will likely need to be disked which would create large clods, allowed to dry, and then field cultivated before planting – an investment of time and labor and potentially a practices that leads to excess soil compaction.

Figure 5 shows what a fall applied treatment of glyphosate + 2,4-D + Canopy EX looks like on May 6, 2006. Notice that all of the winter vegetation is controlled by the addition of Canopy EX to the mixture. A field with this type of control could be planted into without additional soil preparation or spring applied herbicides.

As a final note, use of fall applied herbicides are not the solution to all spring problems, particularly horseweed. Since we have a lot of summer emerging horseweed in southern Indiana, use of fall applied herbicides is not the most effective technique for managing horseweed unless products with significant residual activity are used in the fall. I will discuss that in more detail later in the summer as we begin planning fall herbicide applications.

Figure 1. Yellow fields in Indiana with cressleaf groundsel

Figure 3. Conventional-till practice practiced in the field on the left.

Figure 2. Fall applications of glyphosate were applied on the left field, the right field did not receive a fall application.

Figure 4. Large clods from disking.

Figure 5. Fall application of glyphosate + 2,4-D + Canopy EX. Taken May 6, 2006.

![]()

Cressleaf Groundsel and Indiana – (Glenn Nice, Bill Johnson, and Thomas Bauman)

In the past mustards were given the reputation of turning fields yellow; however, for the past several years it may be ragworts and groundsels doing all the work. In our various travels throughout the state Bill, Tom and I have been seeing large amounts of creassleaf groundsel. The phone calls we have received also suggest that cressleaf groundsel is a spring occurrence.

Packera spp. are members of the Aster family (Asteraceae/Compositae). Many people previously knew them as Senecio species, but they are being placed in the Packera genus (USDA). In Indiana we generally have cressleaf groundsel (P. glabella), a winter annual. Occasionally I see golden ragwort (P. aureus) in Indiana which is a perennial. Other than one being an annual and the later being a perennial, cressleaf groundsel will have a thick hollow stem and golden ragwort will have slender stems.

Cressleaf groundsel starts as a rosette (Figure 1). The young leaves of cressleaf groundsel can be variable, being lanceolate to deeply lobed. Mature leaves generally have deeply lobed margins and are alternately placed on the stem. Yellow disk like flowers can be seen from April to September (Britton and Brown 1970). However, in Indiana we usually see the flowers in the early spring. Flowers are 9/16 to 13/16 of an inch in diameter. The seed are in a reddish brown achene. Each achene has a pappus for wind dispersal of seed. Seed heads can look like small dandelion seed heads. Cressleaf groundsel can be told apart from mustards by counting the petals. Mustards have four petals per flower, cressleaf groundsel will have 7 to 12 petal like ray flowers (Figure 2). Common groundsel can be found along roadsides, in pastures, and in wet nutrient rich areas. It grows best in cool wet conditions and will die out in periods of hot and dry conditions, as is often found in an Indiana summer.

Packera spp. species can be toxic to cattle and horses. Cressleaf groundsel, not as toxic as its cousin to the West, tansy ragwort (Senecio jacobaea), can still produce toxic alkaloids. Poisoning is most often a chronic, taking several weeks to show symptoms. Senecio (Packera) poisoning is called “seneciosis” or “pictou disease” (McCain et.at.). Symptoms in cattle can range from scaly noses, rough coats to listless, and a decreased apatite with digestive problems (diarrhea or constipation). In severe cases, cattle may be jaundiced and/or photosensitive. Calves can develop swollen jaws. Horses can become nervous and have the “sleepy staggers” bumping into objects or becoming entangled in fences. Long term exposure can cause liver damage. To prevent seneciousis learn to identify Packera spp. species in the pastures and in hay. Remove contaminated hay and avoid feeding on senecio infested pastures.

For information on the control in soybean and corn fields see the companion article “What Do We Do About the Yellow Fields?”. The use of metsulfuron methyl (Cimerron®, Ally®) has been reported to control of cressleaf groundsel in grass pastures. The use of 2,4-D in the fall or early spring while the plant is still in the rosette stage is a cost effective control method. However, consistancy of control begins to drop when cressleaf groundsel begins to bolt.

There has been some research on the use of biological controls. In the case of ragworts, insects have been investigated as possible control mechanisms. Much of the research has focused on the cinnabar moth (Tyria jacobaeae) and the ragwort flea beetle (Longitarsus flavicornis and L. jacobaeae).

Reference:

Britton, N. and A. Brown. 1970. An Illustrated Flora of the Northern United States and Canada; Volume 3 (Gentian to Thistle). Dover Publications, Inc., New York. pp 540-544.

McCain, J.W., R.J. Goetz, T.N. Jordan. Indiana Plants Poisonous to Livestock and Pets. Cooperative Extension Service, Purdue University. WS-9.

USDA, Plant Data Base. Accessed May 6, 2006. http://plants.usda.gov.

Figure 1. Cressleaf grounsel rosette (Photo by Glenn Nice).

Figure 2. Flowinger cresleaf groundsel (Photo by Glenn Nice)

![]()

Herbicide Resistance Screening Available at Michigan State University Diagnostic Services - (Steven Gower, Michigan State University and Bill Johnson, Purdue University)

Herbicide resistance in weeds is a growing concern for growers, due largely to the recent occurrence and spread of glyphosate-resistant horseweed and occasional failures to control giant ragweed and common lambsquarters in Roundup Ready crops. Currently, there are more than 180 weed species resistant to one or more herbicides in the world (Heap 2006). These weeds have developed resistance to very effective herbicides in field, vegetable and fruit crops, as well as tree plantations and nurseries.

Confirming herbicide-resistant weed populations is the first step of any resistance management program. Verification will provide producers with the knowledge to implement the best possible management strategies, with the ultimate goal of preventing or limiting the spread of herbicide-resistant weeds.

For 2006, Purdue University weed scientists will continue screening weed samples for tolerance to glyphosate, but not other herbicides. Samples can be sent to:

Bill Johnson or Glenn Nice

Department of Botany and Plant Pathology

Lilly Hall of Life Sciences

915 West State Street

West Lafayette, IN 47907

There is no charge for this service and the cost is covered by a grant from the Indiana Soybean Board for this year. In 2007, it is unlikely that we will be able to do this for free.

Sampling Procedures:

- Send either mature seeds or seedheads.

- Collect seed or seedheads from 20 to 40 widely plants through the field.

- Air dry seed/seedheads prior to packaging to prevent mold.

- Label the package containing the seed or seedheads with the sample reference, name, and location.

- Mail the samples and the survey form together to the address listed above.

This address will take you to a Herbicide Resistant Weed Screen form: http://www.btny.purdue.edu/weedscience/2003/Articles/sform9-2-03.pdf.

If herbicide resistance to herbicides other than glyphosate is suspected in any weed species, samples may be submitted to MSU Diagnostic Services for a resistance screen. In most circumstances, a whole plant pot assay established from seed will be the standard test for herbicide resistance confirmation. Mature, high quality seed or seedheads should be collected from suspicious plants in late summer or fall and submitted in a paper bag or envelope. Do not seal plants or seed in plastic!

Fees associated with herbicide-resistant weed testing for fields in Indiana are $75 per sample per herbicide site of action (i.e., ACCase inhibitors, ALS inhibitors, Photosynthesis inhibitors). Each additional site of action is $30 per sample. Samples submitted from Michigan producers are $50 per site of action and $20 for each additional site of action.

Please contact Steven Gower (517-432-9693, sgower@msu.edu) with any questions regarding resistance confirmation or sample collection. Samples can be mailed to:

Michigan State University

Diagnostic Services

101 Center for Integrated Plant Systems

East Lansing, MI 48824-1311

Attn: Steven Gower

Many surviving horseweed in soybean field

![]()