Time to Scout Smart: High Risk Fields and Potential Pests - (Christian Krupke and John Obermeyer)

• Corn planted into grass = armyworm risk

• Wheat in areas of dense growth = armyworm risk

• Corn where weedy growth existed = cutworm risk

• Soybean first emerging is at risk for bean leaf beetle.

Corn & Armyworm - Corn that has been no-tilled into an abandoned wheat stand or a grass cover crop should be inspected immediately for armyworm feeding in southern Indiana. Hatched larvae will move from the dying grasses to emerging/emerged corn. Armyworm feeding gives corn a ragged appearance, with feeding extending from the leaf margin toward the midrib. Damage may be so extensive that most of the plant, with the exception of the midrib and stalk, is consumed. A highly damaged plant may recover if the growing point has not been destroyed. If more than 50% of the plants show armyworm feeding and live larvae less than 1-1/4 inches long are numerous in the field, a control may be necessary. Larvae greater than 1-1/4 inches consume a large amount of leaf tissue and, as with any large insect, are more difficult to control. If armyworm are detected migrating from border areas or waterways within fields, spot treatments in these areas are possible if the problem is identified early enough.

Armyworm feeding on 1-leaf corn (Photo by Dan Childs)

Wheat/Grass Pasture & Armyworm - Examine plants in various areas of the field, especially where plant growth is dense. Look for flag leaf feeding, clipped heads, and armyworm droppings on the ground. Shake the plants and count the number of armyworm larvae on the ground and under plant debris. On sunny days, the armyworm will take shelter under crop residue or soil clods. If counts average approximately 5 or more per linear foot of row, the worms are less than 1-1/4 inches long, and leaf feeding is evident, control may be justified. If a significant number of these larvae are present and they are destroying the leaves or the heads, treat immediately.

Armyworm feeding on wheat heads

Corn & Black Cutworm – As outlined in previous Pest&Crop articles, the moth flight into the state has been heavier than ever this year. Trapping is over for this year, now it is time to wait and see what is found in terms of larval feeding. Generally the moths that arrived weeks ago were attracted to winter annual weeds for egg-laying. Those eggs have hatched, and caterpillars are out in those fields now, either feeding on dead/dying weeds or starting to move onto emerged corn. Insecticides, whether soil or seed-applied, should not lull producers into a false sense of security, as larger larvae are able to continue their feeding. Timed scouting, and careful assessment of damage can go a long way in preserving a stand of corn.

Cut plant pulled under soil surface by black cutworm

Soybean & Bean Leaf Beetle – These beetles awoke from their winter’s nap some time ago and have been feeding on forages and other legumes (e.g. clover) while waiting for soybean to be planted and emerge. Amazingly, they are able to “smell” and subsequently find first emerging soybean, whether near a wood’s edge or in the middle of a large field. Once plants have emerged throughout a field, beetles will typically dissipate to non-economic levels. First planted and/or first emerging soybean seedlings should be inspected for their feeding on cotyledons and unifoliate leaves. Although this initial leaf feeding may look serious, only extensive cotyledon damage is cause for serious concern - if cotyledons are being destroyed before the unifoliate leaves fully emerge or if the growing point is severely damaged, reduced yields are likely. However, once trifoliate leaves have unrolled, soybean can tolerate up to about 40% defoliation without yield loss. It may look ugly, but they can take a beating.

Bean leaf beetle feeding on cotyledon

Eye-catching, but non-economic unifoliate leaf feeding

![]()

Click here to see the Black Light Trap Catch Report

![]()

What Do We Do About the Yellow Fields? - (Bill Johnsonand Glenn Nice)

There are a lot of yellow fields out there, especially in the southern half of Indiana. The weed species is cressleaf groundsel, aka, ragwort, butterweed, senecio, “that mustard thing” (Figure 1). See a related article for more information on the biology and identification of this weed.

Figure 1. Yellow fields in Indiana with cressleaf groundsel

Glenn and I have received a number of questions about control of this weed this past week because the recent wet spell did not allow burndown applications to be made in a timely manner during late April. Now we have fields with groundsel, plus chickweed, henbit, deadnettle, and winter annual grass in the seed set stage, and summer annuals that have started to emerge such as giant foxtail, giant ragweed, common lambsquarters, black nightshade, pigweeds and waterhemp and bolting horseweed (marestail) that emerged in the fall and seedling horseweed that emerged this spring. So what do we do? There are a couple of different herbicide programs to consider. In all cases, it is going to be best to add some 2,4-D to the mix to improve control of groundsel, bolting horseweed, and the summer annual broadleaf weeds. The chickweed and other winter annuals won’t be controlled well by anything since they are in the seed set stage, but they could be desiccated more rapidly if a paraquat-based program is used. Control of groundsel will also be a challenge since it is large, flowering and many of the lower leaves have fallen off of the plant, so herbicide uptake is limited by lack of leaf area.

Key Considerations. If flowering (Figure 2) groundsel is the primary target, you can use glyphosate + 2,4-D or 2,4-D + paraquat + Sencor (beans) or atrazine (corn) if you desire more rapid desiccation of weed biomass. In the glyphosate-based program, use the 1.5 lb ae/A rate with 1 pt/A of 2,4-D. Most labels require you to wait 7 days before planting corn or soybean with this rate of 2,4-D. In the paraquat-based program, use the upper end of the rate range for more effective control of large weeds. In our research, these programs have usually provided about 85 to 90% control of large, flowering groundsel. However, if the weather stays cool and wet, expect some regrowth of groundsel with either herbicide program that can be cleaned up with various postemergence treatments in corn or soybean.

Figure 2. Flowering cressleaf groundsel

How to Prevent this from Happening Next Year. This situation is a good educational opportunity to see the value of fall applied herbicides for managing groundsel. Groundsel is primarily a winter annual and fall applied treatments containing glyhposate and/or 2,4-D are very effective in reducing infestations. In Figure 3 (taken May 6, 2006) at the Southeast Purdue Ag Center, the field on the left was sprayed with glyphosate in the fall, the field on the right was not treated. Although we do not have 100% control of all weeds on this date, the field on the left is noticeably drier and will be planted 1-3 days earlier that the field on the right. Our recommendations would be to start with a clean field in both cases, so the weeds present in both fields should be controlled before planting with tillage or a burndown herbicide. If no-till practices are used, the field on the left could be managed effectively with the 0.75 lb ae/A rate of glyphosate alone. Because the field is in southeast Indiana and glyphosate-resistant horseweed is widespread in this area, so, we would also recommend using 2,4-D with glyphosate or a paraquat-based program with 2,4-D and a triazine. A low rate of paraquat could be used in this field compared to the field on the right. For the field on the right, we would recommend using a 1.5 lb ae/A rate of glyphosate with 2,4-D or a paraquat-based program mentioned above. The paraquat rate would need to be towards the upper end of the labeled rate range. If conventional-till practices are used, the field on the left will likely require at least 1 less field preparation pass with a field cultivator that the field on the right. The field on the right will likely need to be disked which would create large clods (Figure 4 and 5), allowed to dry, and then field cultivated before planting – an investment of time and labor and potentially a practices that leads to excess soil compaction.

Figure 3. Fall applications of glyphosate were applied on the left field, and the right field did not receive a fall application

Figure 4. Conventional tillage practiced in the field on the left.

Figure 5. Large clods from disking

This image shows what a fall applied treatment of glyphosate + 2,4-D + Canopy EX looks like on May 6, 2006 (Figure 6). Notice that all of the winter vegetation is controlled by the addition of Canopy EX to the mixture. A field with this type of control could be planted into without additional soil preparation or spring applied herbicides.

Figure 6. Fall application of glyphosate + 2,4-D Canopy EX. Taken May 6, 2006.

As a final note, use of fall applied herbicides are not the solution to all spring problems, particularly horseweed. Since we have a lot of summer emerging horseweed in southern Indiana, use of fall applied herbicides is not the most effective technique for managing horseweed unless products with significant residual activity are used in the fall. I will discuss that in more detail later in the summer as we begin planning fall herbicide applications.

![]()

Bacterial Mosaic on Wheat – (Gail Ruhl and Kiersten Wise)

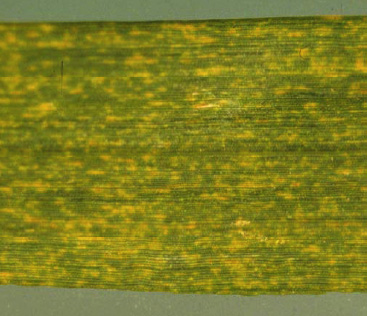

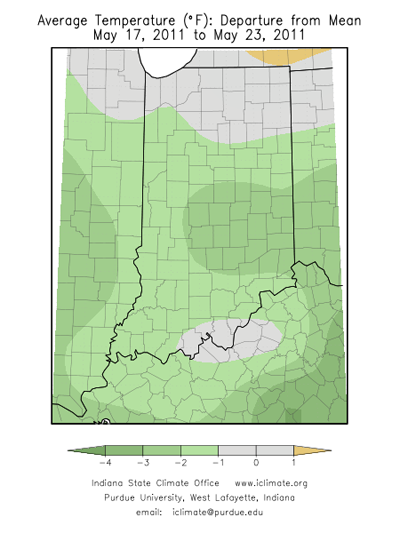

Within the past several weeks the PPDL has received wheat samples with virus symptoms from Adams, Posey, and Tipton counties that have tested negative for virus but positive for Bacterial Mosaic. This is the first report for Bacterial Mosaic in Indiana however not the first report in the Midwest (first report from Illinois in 1990). Bacterial Mosaic, caused by Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. tessellarius (Cmt), produces symptoms resembling viral infections. Flecking and small yellow lesions that coalesce into streaks are typically uniformly distributed over the leaf blade resulting in a mosaic-like pattern. No bacterial exudates are produced. It appears that there may be degrees of resistance among cultivars. The PPDL uses a serological ELISA test kit from Agdia Inc. to test for the presence of Cmt in symptomatic leaf tissue and multiplex PCR analysis to test for the presence of WSSMV, WSMV, WSBMV and BYDV. The following fact sheet from Texas AgriLife Extension Service provides additional information on Bacterial Mosaic: <http://amarillo.tamu.edu/files/2010/11/BacterialMosaic.pdf>

Figure 1. Mosaic like symptoms spread over the entire leaf surface (Photo credit: Tom Isakeit)

Figure 2. Magnification of advanced foliar symptoms. Unlike other bactgerial infections, neither oozing nor water-soaking is present (Photo credit: Tom Isakeit)

![]()