Chemical Control

The word pesticide is often used as a synonym for insecticide, but this is actually incorrect. Pesticides refer to a broad group of chemicals designed to control pests. While insecticides are one type of pesticide, there are many other types of pesticides as well. Some other examples are herbicides, which are used to control plants, and rodenticides, which are used to control rodents.

There are many different kinds of insecticides. Some, such as sulphur and arsenic, have been used for more than 3,000 years. Others are just being developed today. Because there are so many insecticides, they can be grouped in many different ways, including by chemical makeup, by how they work, by their form, and by what insects they target. For example, insecticides are often placed into groups or classes of chemistry, depending on how they are synthesized. They are given common names that can relate back to the specific chemical name or chemical structure.

Other times insecticides are grouped by the method in which they kill insects, or their mode of action. These insecticides may kill by interfering with a specific part of the insects nervous system, growth and development, or digestion.

Still other ways to describe insecticides involve their mode of entry, or how they get into an insects body. Some are ingested while the insect is feeding, some are taken in as the insect respires, and others rely on contact with the insects epidermis.

In practical applications, pest managers may group insecticides by what insects they control, while in other situations, they group them by what formulations the insecticide is purchased and used (liquids, granules, fumigants, etc.).

Pest managers must understand the insecticides that they use, including the common and chemical names, modes of action, modes of entry, formulations, and target pests affected.

Use of synthetic chemical pesticides is an important component of most IPM strategies. Chemical treatments are especially effective because they can be applied with relative ease and can quickly bring a high pest population down to an acceptable level. When used in this manner and for this purpose, chemicals can be an integral part of an IPM program.

When pesticides are continually and exclusively relied upon to maintain pest populations at low levels, problems inevitably arise. Pesticides are toxic and are designed to kill. As a result, there is always a potential threat of pesticide poisoning to people or other animals that are not the target.

Chemical pesticides are notorious for their ability to move from an intended target zone to another. They may move through water or air into an unintended zone, where significant damage may occur to people, nontarget animals, plants, or the environment. Chemical pesticides may also change formsfrom liquids to gases or from solids to liquidand pose very significant risks.

Sound IPM requires selecting only those insecticides that have the correct formulation, concentration, and proven result for the pest and site intended.

It is unrealistic to expect to eliminate all pests. Notwithstanding the broad-spectrum, long-residual pesticides used in the 1960s and 1970s, it has become clear that complete eradication of pests is impossible. In most situations, small pest populations that are monitored carefully over time and managed in such a way that they do not increase beyond certain tolerance levels become acceptable. When compared with the potential negative human and environmental health effects that complete pest elimination would causenot to mention the costs of total reliance on chemical pesticidesa low, well-managed population is preferable.

Recently, great strides have been made in developing low-impact chemistries. These are environmentally friendly, narrow-spectrum (more targeted), least-toxic pesticides that have been developed by the chemical industry. As the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency registers these for use, other older, high impact, and less environmentally compatible pesticides, are being removed from the marketplace.

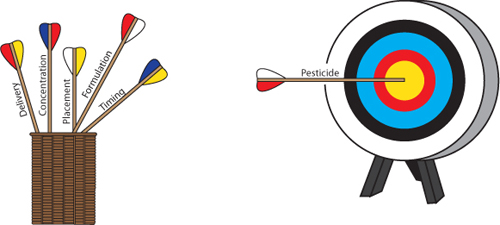

Always use the best pesticide delivery, concentration, placement, formulation, and timing when shooting for IPM. The solution to a specific pest problem does not always involve a new or better pesticide. Often the difference between success and failure in managing a pest population lies in knowing where, when, and how to apply a selected pesticide.

Targeting pesticide applications to only those areas where monitoring has determined a need for control (spot treating) decreases the total amount of pesticide applied and conserves natural biological controls already in place. IPM dictates that spot treatments replace blanket treatments wherever possible.

Using new technologies to deliver pesticides directly into the area where pests are presentthat is, the target zonediminishes the probability of exposure to nontarget organisms, decreases the quantity of pesticides needed for treatment, and increases pesticide effectiveness. For example, replacing whole-room or even baseboard treatments with crack-and-crevice-only applications is one way of targeting pesticides in buildings and structures. Injection techniques may be used to deliver ever smaller amounts of pesticides into soils or trees in the urban landscape. Select pesticides also may be absorbed and distributed throughout the plant, ultimately killing only those insects feeding directly on it. This is another example of targeting. Spot-treating crops, rather than treating the entire field, where inspections have indicated that pests are present is a method of targeting pesticide applications in agriculture.

Targeting is sound IPM.

Timing of insecticide applications is critical. IPM dictates that pesticides only be applied when they can prevent pest damage. In some instances, only one stage of an insect is damaging. Therefore, knowing when the pest does its damage is important. Application timing must be a part of an IPM strategy.

Proper timing of pesticide applications is sound IPM.

Professional IPM continually incorporates new procedures and technologies into pesticide-application methods, thereby decreasing both the populations of pests and the negative risks associated with pesticide applications. Development of pesticide-laced baits has greatly improved the ability of structural pest managers to control rodent and insect pests, such as mice, rats, ants, cockroaches, and termites. Baiting techniques significantly decrease the amount of toxic materials applied in the urban environment and yet achieve pest-population controls equal to or better than traditional methods.

Good IPM strategy requires the use of the most effective pesticide applied at the best possible time and in the best possible manner to only those areas that are known to harbor damaging levels of pests.

|