| Plague |

|

Plague has surfaced several times in major, world-wide epidemics, one of the most important of which was the so-called "black death" that devastated Europe in the 14th century, when an estimated 25,000,000 people died. Historically, plague outbreaks have started slowly with transmission of the disease agent, a bacterium, via the bite of infected rodent fleas, primarily the Oriental rat flea, but then developed into rapidly growing epidemics involving human-to-human transmission (see below).

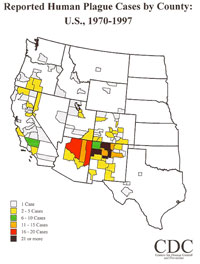

Today, plague exists as a disease of wild rodents in most of the arid regions of the world, including the western U. S. and southwestern Canada. Every year, a small number of people (approximately 10-15 per year) in the southwestern U.S. become infected with plague, typically after venturing into or living in or adjacent to areas in which they are bitten by infected fleas that are parasites of wild rodents. One of the most important vectors is a flea species with the scientific name Oropsylla montana. This flea is a parasite of the rock squirrel, Citellus variegatus, which is a common reservoir animal, from which fleas acquire plague bacteria when they take a blood meal. |

| Causative agent |

|

| Geographical distribution of cases |

|

| Symptoms of infection |

|

| Reservoir hosts of Yersinia pestis in the U.S. |

|

| Vectors of Yersinia pestis in the U.S. |

|

| Modes of Transmission |

|

| Diagnosis of infection |

|

| Treatment of infection |

|

| Prevention of infection |

|

|

Control of vectors |

|

The initial infection following feeding by an infected flea is marked by painful, swollen lymph nodes, initially

in the groin region. This form of plague is known as "bubonic plague," which, if untreated, can

develop into a form of plague known as "septicemic plague." In septicemic plague, bacteria invade

the blood and infect major body organs. In addition to damaging organs and causing internal hemorrhage, septicemic

plague can develop rapidly into a highly infectious disease condition known as "pneumonic plague."

In pneumonic plague, bacteria infect a patient's lungs and may be spread via coughing. If untreated, fatality

rates of septicemic and pneumonic plague are as high as 50-90%, and they approach 15% even when treated promptly

with antibiotics.

The initial infection following feeding by an infected flea is marked by painful, swollen lymph nodes, initially

in the groin region. This form of plague is known as "bubonic plague," which, if untreated, can

develop into a form of plague known as "septicemic plague." In septicemic plague, bacteria invade

the blood and infect major body organs. In addition to damaging organs and causing internal hemorrhage, septicemic

plague can develop rapidly into a highly infectious disease condition known as "pneumonic plague."

In pneumonic plague, bacteria infect a patient's lungs and may be spread via coughing. If untreated, fatality

rates of septicemic and pneumonic plague are as high as 50-90%, and they approach 15% even when treated promptly

with antibiotics.