Pest & Crop Newsletter, Entomology Extension, Purdue University

- Indiana's Major Moves, Soybean Aphid to Buckthorn

- Nematode Updates- Winter Annuals and Management of soybean Cyst Nematodes

Indiana’s Major Moves, Soybean Aphid to Buckthorn – (John Obermeyer, Christian Krupke, and Larry Bledsoe)

- An unprecedented number of soybean aphids have moved to Indiana buckthorn.

- Buckthorn, the soybean aphid's primary host, is used for egg-laying and overwintering.

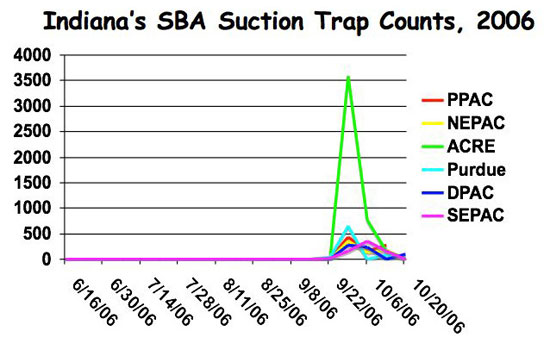

- Soybean aphid suction trap captures have been very high this fall.

- Pest managers should be prepared to scout for soybean aphid next season.

Winged and nymph soybean aphid on buckthorn leaves.

An incredible entomological phenomenon has occurred among the whirling combines this fall, but has mostly gone unnoticed. Massive numbers of winged soybean aphids have left maturing soybean fields in search of their overwintering host, buckthorn. In some area of the state, clouds of these gentle flying insects have rivaled the soybean dust floating throughout the countryside. The populations seen in late September on buckthorn were impressive, now for “the rest of the story.”

Common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) is a shrubby tree that can form dense thickets on the edges of woodlands. Because of its hardiness, it was brought to North America from Asia decades ago for fencerows and wildlife habitat. It is now classified as an invasive species because of its ability to outcompete native forest species. Ironically, it is considered an ornamental by many, and can be found around home and business landscapes. Buckthorn exists in scattered dense patches in Indiana, with the highest concentrations of common buckthorn occurring in the northern Midwestern States (Minnesota, Wisconsin). Buckthorn is considered the soybean aphid’s primary host because this is where eggs are laid in the fall for overwintering. For this reason, availability of buckthorn is necessary for the aphid’s life cycle.

Larry Bledsoe observing soybean aphid on a buckthorn bush in the middle of Purdue campus

In late September we observed local patches of buckthorn being inundated with soybean aphid, winged and nymphs. Interestingly a lone buckthorn bush in the middle of campus, at least a mile away from the nearest soybean field, was thoroughly infested with aphids. This and similar sightings prompted researchers Bob O’Neil and David Voegtlin, from Purdue University and the University of Illinois respectively, to investigate known buckthorn patches in the Great Lakes region. In some areas, especially northern Indiana, the density of aphids and eggs were remarkable. These observations correlate well with the unprecedented high numbers of winged soybean aphid captured in Indiana’s suction traps, see graph below.

Winged soybean aphid and eggs next to a buckthorn bud.

While the soybean aphid migration to and egg laying upon buckthorn this fall may sound like impending doom for next year’s soybean crop, there is a glimmer of hope. In the midst of the birthing and egg-laying aphids were multitudes of predators: Asian lady beetles, syrphid fly larvae, minute pirate bugs (the tiny ones that bite), etc. The previously mentioned buckthorn bush on campus was completely aphid-free in one week’s time because of the numbers of natural enemies. Where low densities of buckthorn exist the predators seem to have won out. However, the “good guys” were probably overwhelmed with aphids/eggs in large buckthorn thickets. This is evident by some buckthorn, observed by Bob and Dave, still heavily infested with eggs.

Close-up of a soybean aphid colony on a buckthorn leaf.

Asian lady beetle feeding on aphids on buckthorn leaf.

For 2007, as in the previous three odd years (2001, 2003, 2005), the stage seems to be set for a significant risk of soybean aphid infestations next season. Several variables need to be played out before anyone can say with certainty what will occur. For example, predators will likely continue to feed on overwintering eggs this fall and early spring reducing next year’s numbers further. Though it may seem counter-intuitive, early aphid movement to soybean may actually prevent them from getting to yield-threatening levels throughout the summer because of a boost in natural enemy numbers. As always, timely soybean planting and ample moisture throughout next year’s growing season will reduce the soybean aphid impact, even with long-term, low infestation levels. Simply put, timely soybean scouting and treatments when necessary are the most efficacious and economic way to deal with pests such as soybean aphid. More to come as this story unfolds for next spring.

![]()

Nematode Updates-Winter Annuals and Management of Soybean Cyst Nematode – (Jamal Faghihi, Bill Johnson, and Virginia Ferris).

Once again winter weeds like henbit and purple deadnettle are beginning to show up in fields around Indiana. These two winter weeds are particularly susceptible to soybean cyst nematode. For the most part, we used to think that the active growth period for these weeds does not coincide with SCN activities. However, over the last couple of years we have closely observed winter weed emergence and have noted that henbit and purple deadnettle can emerge in the spring, late summer and fall. Emergence in the spring can occur as early as mid March and generally ceases in late April. Late summer or fall emergence can begin in late-August when we have cool wet weather conditions. So now, we have evidence that the life cycles of winter weeds and SCN do overlap and the potential exists for SCN population increases on winter annual weed hosts.

SCN is not physically active when soil temperature falls below 50°F. The optimum temperature for soybean cyst nematode is 75°F. At 75°F the nematodes require about one month to complete one life cycle, about 750 degree days. Winter weed growth is fairly abundant this year and an earlier than usual harvest might encourage more winter weed growth. Recently, we were able to document and report the completion of at least one generation of SCN in the field. Earl Creech, the weed science graduate student working on this project, was able to follow a life cycle of SCN and extract newly developed cysts on roots of purple deadnettle plants in a field in southern Indiana.

The winter annuals in Indiana typically germinate in late fall and mature in early spring. During this time period, under normal conditions, the Indiana soil temperature seldom reaches and stays at the required temperature for SCN development. With warm September weather conditions, completion of an SCN life cycle on winter weeds is a possibility. Growers might have an extra incentive to spray for winter weeds this fall as part of their overall farm management and SCN population control if they have fields with both purple deadnettle and SCN. With funding from the Indiana Soybean Board and USDA CSREES we are continuing to pursue the correlation between winter weeds and soybean cyst nematode. We have yet to accumulate enough data to be able to recommend winter weed management on a regular basis to manage SCN in the northern half of the state, but we are getting close to more definitive answers. We might be able to predict the activities of SCN on winter weeds based on the number of degree days required for SCN to complete the life cycle (750 DD). The accumulation of DD in southern and northern Indiana will be different in different years. We might have to have two sets of recommendations for different parts of the state. We will monitor SCN and winter annuals activities and correlate them with soil temperatures to be able to make better recommendations in the future. Valerie Mock, a graduate student in Weed Science is conducting research to determine whether or not early fall removal timing will have an influence on SCN reproduction on purple deadnettle – stay tuned for more details![]()

Asian Soybean Rust - (Gregory Shaner, Gail Ruhl, and Karen Rane)

- A late arrival, but still imporant.

During the past couple of weeks, we found Asian soybean rust on soybean leaf samples submitted from six Indiana counties: Knox, Pike, Posey, Tippecanoe, Vanderburgh, and Warrick. The first finding for Indiana was in Knox County, and represented the northernmost detection of this disease in the U.S. A week later, the find in Tippecanoe County bested that record by more than 100 miles.

Our soybean harvest was well underway when rust showed up. Even though rains have delayed harvest, virtually all of the soybeans in the state are now mature, so there was no opportunity for the disease to damage this year’s crop in Indiana. The samples on which we found rust were mainly double-crop plantings, or late maturity groups that were far behind in development.

The story of how rust reached Indiana starts in the Mississippi Delta area. The first reports of rust from this region were in late June and early July, on kudzu in Lafayette and Iberia Parishes. It was not until late July that rust was found on soybean in Louisiana, in a sentinel plot in Rapides Parish. On August 1, rust was found on both soybean and kudzu in Jefferson County, Mississippi. From mid August through September, more and more reports of rust came from Louisiana, from sentinel plots and commercial fields. In most cases, incidence of rust (the percentage of leaves with rust) was low. Scouts found moderately severe rust in two commercial fields in late July, one near maturity and another at the R6 stage of growth.

Soybean leaflet with one Asian soybean rust pustule near the edge (circled with black marker pen). The leaflet has numerous brown spot and downy mildew lesions. (Photo by Karen Rane)

Magnified view of the single rust pustule on the leaflet from Knox County. Spores can be seen emerging from the pustule.

(Photo by Karen Rane)

A weather-based spore dispersal and deposition model indicated that from September 22 through 24, spores from the Delta region were carried up the Mississippi Valley into southeastern Illinois and much of Indiana. On Oct 11, Kentucky reported finding rust in three western counties, including Union County, which is just across the river from Posey County in Indiana. We asked County Educators in that area to send any soybean or kudzu leaves that were still green to the Purdue Plant & Pest Diagnostic Lab. The first sample we received was from the Southeast Purdue Ag Center in Jennings County. Some double-crop beans near a security light were still green. We found no rust on these. The first positive sample was from Knox County. Plant pathologists Dan Egel and Sara Hoke collected leaves from a double-crop field on the Southwest Purdue Ag Center. Close examination revealed one pustule on one leaflet. Because the first finding in each state must be confirmed by USDA-APHIS-PPQ, we sent this sample to the Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory in Beltsville, MD for PCR testing, and the positive test results were reported to us on October 18. The next finding was in a sample of 70 leaflets from Posey County. Again, we found rust on only one of the leaflets, but there were 17 pustules on it. In the samples from Warrick, Vanderburgh, Pike, and Tippecanoe Counties there was also only one leaflet with rust. The rusted leaflet from Pike County had 27 pustules in a close group.

Since late September, when the dispersal model predicted spores were being transported north from the Delta area, rust has been found in 26 counties in Arkansas, 17 in Tennessee, 18 in Kentucky, 4 in Missouri, and 8 in Illinois, in addition to the 6 counties in Indiana. The timing of discoveries of rust in the mid South and Midwest indicates that all of these infections arose from a major dispersal event that originated in Louisiana.

Another scenario for spread of rust from the south would be stepwise progression, in which infections would develop perhaps fewer than 100 miles beyond a spore source. As these infections matured to produce pustules and spores, they would become the source for further short-distance northward spread. If rust spread only in that manner, we would not be concerned with the disease until it was in Tennessee or Kentucky.

The events of this fall suggest that viable spores can move long distances in a short period of time. If rains that scrub spores out the air accompany a long-distance dispersion, rust can appear simultaneously over a large area. If the events of late September 2006 were to occur several weeks earlier in a growing season, we could have a major outbreak of rust when the crop is still vulnerable.

We have also learned how difficult it is to detect rust at very low incidence. To make timely fungicide applications we need to detect rust when it first appears. It required as long as 3 hours to examine each sample of leaflets. The entire lower surface of each leaflet was examined through a dissecting microscope. This microscope provides excellent magnification, but at a cost of being able to look at only a small area of leaf in each view. These leaf samples collected late in the season may have been more difficult to examine compared to collections during the summer because there were many brown spot, frogeye leaf spot, and downy mildew lesions, as well as minor wounds. Most leaves were losing chlorophyll. But even earlier in the season, these foliar diseases are present and can make it difficult to find a single, small rust pustule.

This summer and last, weather was dry in much of the South. This may be why rust spread so slowly there until late in the season, until weather became more favorable. If next year or in any future year, the summer is wetter in the South, rust may develop more rapidly there than it has done so far. The events of September and October of 2006 suggest that if that happens, and rust is present in Mississippi, Louisiana, and east Texas, the eastern Corn Belt states could be at risk for soybean rust.

For more information on soybean rust, visit the Purdue Plant and Pest Diagnostic Lab Web site at http://www.ppdl.purdue.edu/PPDL/soybean_rust.html or call the Purdue soybean rust hotline at (866) 458-RUST (7878).

![]()

Purple Soybean Stems – (Shawn P. Conley)

Purple soybean stem.

The purple symptomology we are seeing on both mature and green soybean stems is most likely caused by elevated anthocyanin levels. Elevated anthocyanin levels are more common in soybean cultivars with purple flowers, but can occur in cultivars with white flowers as well. Soybean plants with purple stems have been common across Indiana in 2006. The extent to which we are seeing this phenomenon does correspond with the growing season we are having. As the soybean plant reaches maturity the source-sink relationship for carbohydrates is disrupted. In 2006, we have seen delayed maturity (green stems and prolonged leaf retention) coupled with mature pods. So simply the plant is still producing carbohydrates (sugar) and has nowhere to put it. These sugars are being converted to anthocyanins and expressed in the stem. If you look at the stem, the purple color it is usually occurring on ½ to ¾ of the stem. The back-side (usually north) however remains its normal tawny color. This consistent symptomology suggests that this is a physiological response and not a disease or nutrient deficiency response.

![]()

Post Harvest Training and Recertification Workshop – (Linda Mason)

This is the first announcement for the Post Harvest Training and Recertification Workshop to be held December 7, 2006 in the David C. Pfendler Hall of Agriculture starting at 8:30 AM. CCH credits are being applied for through the State Chemists Office and will be announced in the mailing.

The session content will be:

-

Afllatoxin Prevention & Mycotoxin Management

-

Aeration and Quality Grain Management

-

Pests ID – Who & Why Do You Fumigate?

-

Individualizing the Fumigation Management Plan

-

Confined Space Entry – Grain Bin Safety

-

Pest Management Quiz

This will be your last chance for CCH’s for 2006! Watch our Extension home page for registration information: http://www.entm.purdue.edu/Entomology/ext/index.htm

Bug Scout

"I guess you didn't get around to cleaning this bin!"

![]()