Pest & Crop Newsletter

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alfalfa Weevil Management Guidelines and Control Products– (John Obermeyer and Larry Bledsoe)

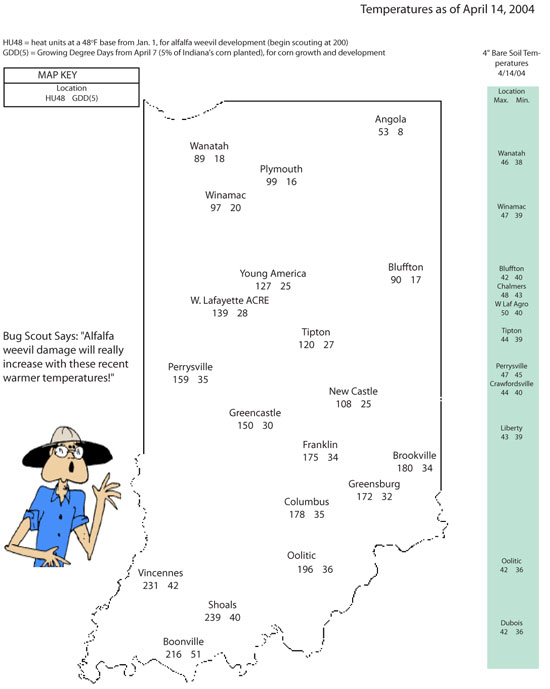

Cooler temperatures (and some snow in southern counties!) at the beginning of the week did not significantly slow alfalfa weevil development and feeding. Cooperators reporting their sampling results from southern Indiana have seen a range of damage from 4 to 88% tip feeding (thanks to Don Biehle, Frankie Lam, Ron Moore, and Betsy Smith). Lyle Busboom reports that tip feeding in Jasper and Newton Counties, northwestern Indiana, is beginning in wind-protected and sandy areas of fields. As field crop activities increase, devoting time to monitor and properly manage this major forage pest will be a challenge. As pest managers have found in the past that you cannot ignore this pest and expect high quantity and quality of hay. In most years, extended hatch of weevil larvae occur in Indiana, with as many as four population peaks seen in southern Indiana during the spring. Due to the phenomenon of multiple peaks, the application of controls should be delayed somewhat to reduce the likelihood that multiple applications of an insecticide will be needed. In other words, if an insecticide is applied too early and there are weevils yet to hatch, the insecticide may not control the later hatching larvae. Producers can manage this pest most effectively by utilizing heat unit accumulations data (base 48°F) to determine when sampling should begin and when an action should be taken, The management guidelines listed below should be used to determine when alfalfa weevil should be controlled in southern Indiana. Refer to heat unit information in each week’s Pest&Crop “Weather Update.“

Is This Going to be a Grub Year?– (John Obermeyer and Larry Bledsoe)

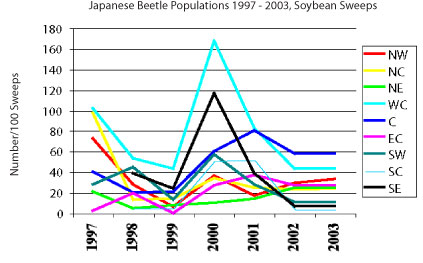

Grub complaints typically increase in frequency during an early planting season. We consider planting before the third week of April to be early. However, approximately 10% of last year’s corn was planted before that period and we heard of very few grub problems. Obviously there’s more to it than just planting date. Factors such as grub populations, spring’s growing conditions, and soil type all likely play a part. Japanese beetle is the predominant grub species found in field crops in Indiana. Eggs laid last summer and fall in the soil hatch into grubs that feed on living and decaying plant matter. Grubs overwinter as partially developed larvae about 4 to 6 inches deep in the soil. Little is known or understood about their ability to withstand extremes in soil temperature, moisture, and freezing/thawing action through the winter months. We believe there is a correlation between colder than normal fall and winter soil temperatures and fewer Japanese beetle the following summer. Refer to the following graph of Japanese beetle numbers from soybean sweeps taken in the years 1997 to 2003. There you can see that beetle numbers have been unimpressive the last several years when considering statewide abundance. Some local populations can be very large. Seed already planted will be subjected to cooler soils and extended germination/emergence. If corn is slow to emerge and grubs are found nearby, it is often assumed that they are feeding on the seed/seedling. However, cool soil temperatures are usually the reason for slow plant emergence. Even with their presence, grubs may or may not be damaging the crop because they too are less active in cool soils. Once soils warm up... you can bet grubs will feed on roots but they are also feeding heavily on organic matter in the soil too. The length of the feeding period and grub population will govern to a large degree as to whether economic damage will occur. In other words, the longer the interaction between grub and seedling, the greater the likelihood of damage. This interaction increases as soil temperatures decrease.

Japanese beetle grubs feed on both living and dead material when they crawl to the upper soil profile in the spring. Soils low in organic matter and crop residues will encourage grubs to move horizontally in the soil profile until suitable food sources are found. Corn or soybean roots within their “grasp” certainly will be fed on. Should you visit a field with suspected grub damage, be certain to dig between rows as well as underneath crop residues. There you will likely find as many, if not more, healthy grubs in the soils that have significant organic material. Grubs in sandy or timber soils (i.e., low O.M.) will concentrate in root zones.

Since rescue treatments are not available, the most effective way to control grubs is to apply a soil insecticide at planting (see table below). If an economic grub population is observed in a field that has already been planted and the stand is threatened, a soil insecticide could be used as part of a replant operation. Replanting, however, is not recommended unless a critical level of plants is being significantly damaged or destroyed by grubs. Remember that a number of factors can cause stand reductions. If a stand is declining due to grub activity, make sure that the grubs are still actively feeding on the roots before making a replant decision.

Click for Table.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

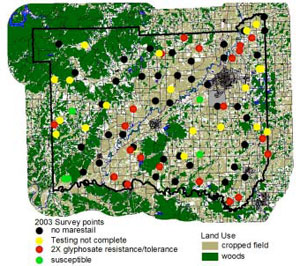

Glyphosate-Tolerant/Resistant Marestail is Widespread in Southeastern Indiana Counties- (Jeff Barnes, Bill Johnson, and Glenn Nice) In last week’s Pest & Crop we discussed results of a survey and screening effort aimed at identifying counties with populations of marestail that have resistance or increased tolerance to glyphosate. In this article, we will begin discussing our efforts to locate specific areas within a county where resistant/tolerant populations are occurring. This article is the first in a series of articles which will show locations of tolerant/resistant populations in specific counties in Indiana. Only four counties in southeast Indiana had confirmed sites with resistant-marestail at the beginning of the 2003 growing season. Following our intensive survey efforts in southeast Indiana and a few selected counties in the northeast and west central portions of the state, we have concluded that 19 counties have marestail populations with some degree of increased tolerance or resistance to glyphosate.

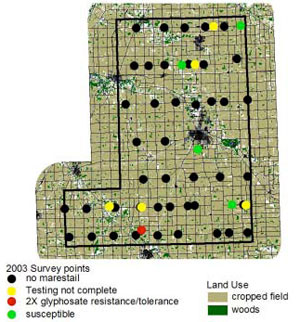

A component of the survey project was to not only identify new pockets of resistance but also to establish the frequency and distribution patterns of resistance at the county level. The survey effort targeted soybean fields and was conducted in the fall of 2003. Random soybean fields were identified through aerial imagery and land use maps complied by the Purdue Center for Advanced Applications in Geographic Information Systems. Within each county, the number of survey sites was selected so that the survey scale fell within the range of 1 field for every 2,500 to 4,000 acres. Driving routes were developed that linked the random GPS selected fields. Seed samples were collected from marestail plants observed within the randomly selected soybean fields. Random sampling was supplemented by collecting seed samples from non-cropped sites and from soybean fields with marestail plainly visible above the crop canopy which were observed along the driving route. Supplemental samples were meant to ensure that pockets of resistance were not missed by the random site selection method. Maps showing specific locations of glyphosate-resistance/tolerance within a county are currently being developed as results of greenhouse trials become available. While these maps are not complete and some samples have yet to be tested, they will be beneficial in identifying resistance pockets at the county level. Unfortunately most of the counties in southeast Indiana appear to have widespread resistance as depicted in Figure 1. Marestail populations that were tolerant/resistant to a 2X glyphosate application are shaded in red. Throughout the major cropping regions of Jackson county marestail populations were discovered that are resistant or tolerant to glyphosate. This map is not complete as many samples are still in the testing process (yellow dots) so the situation could actually be worse than this map currently depicts. The situation in Jackson County is representative of what we observed during the survey effort last fall in throughout southeast Indiana even as far north as Shelby County. We also noted last week that new resistant pockets have been found in southwest, west central, and northeast Indiana. In these areas resistance appears to be rather isolated and is confined to a localized region. Figure 2 depicts the pocket of resistance in Wells County where our survey efforts examined 53 sites for the presence of marestail, but only 10 samples were collected. Of these ten samples, three were from soybean fields and one of those (represented by the red dot) was tolerant to a 2X application of glyphosate. As we finish off our screening efforts in the greenhouse, we will develop more of these maps and eventually place them on the Purdue Weed science website in a section dedicated to the topic of herbicide resistance.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||