Pest & Crop Newsletter

|

||||||||||||||||||

Time for Rootworm Sampling– (John Obermeyer and Larry Bledsoe)

Rootworm larvae have been hatching and seeking corn roots for well over a week in northern counties and two or more weeks in southern counties. First, the larvae are very small and live mostly within the roots. As they increase in size, so does their appetite. They will feed both inside and outside of the roots, causing tunneling and pruning. Earliest planted (most mature) corn has the highest risk of root injury. Late planted (small seedlings) can be injured if the number of eggs in the soil is unusually high. Remember, we had a large number of rootworm beetles present last season, especially in soybean fields in northern counties. It would be wise to sample roots of plants in high-risk fields, especially where insecticide efficacy is in question. To sample for rootworms, use a shovel and lift out the root mass and surrounding soil and place on a dark surface (black plastic garbage bags work well). Carefully break up the clods and sort through the soil. Look for 1/4 to 1/2 inch long, slender, creamy-white larvae with brownish-black heads and tails. Once the soil has been separated from the root mass, inspect it for root scarring and pruning. You may find the larvae under the leaf collars that are close to nodal roots; tear these leaves away to check. Also, you may even observe the rootworms sticking out of roots. Repeat this process with several plants representing different areas of a field. An average of two or more larvae per plant represents a rootworm population that signals the need for a cultivation application. Insecticides applied after planting should be directed toward the base of plants. It is also important to throw soil up around plants to incorporate the insecticide and promote the establishment of brace roots. A good brace root system will help prevent plant lodging and reduce losses due to rootworm feeding. If a no-till field has an economic population of larvae, placing the insecticide on top of the ground will normally not be effective. The only exceptions might be if the soil insecticide is watered in through irrigation or rainfall (ideally a half inch or more). Two liquid soil insecticides, Furadan 4F and Lorsban 4E, are labeled for post-directed applications. If one decides to mix the insecticide with a liquid nitrogen source for a sidedress application, compatibility checks should be made. Broadcasting the insecticide will greatly diminish rootworm efficacy. A QuickTime movie of rootworm larval sampling can be viewed at http://www.entm.purdue.edu/entomology/ext/fieldcropsipm/videos.htm.

Critters Found Among Damaged/Dead Seeds and Seedlings– (John Obermeyer and Larry Bledsoe)

We’ve received calls this season concerning unidentified moving objects (UMOs) around seed or seedlings that are stunted and/or dying. While pest managers have been checking on row skips or stunted plants they expect to find grubs or wireworms and find UMOs instead. The UMO descriptions given over the phone or samples sent to us indicate that these critters are not causing damage. Unfortunately, a complete pictorial guide to the fauna of agricultural soils doesn’t exist. The following are a few possibilities of small critters that you might see with good eyes or a 10X magnifying lens: No legs or mouth, worm-like, translucent to whitish– Often described as nematodes, with many being present in or around damaged areas of the seed/seedling. You CANNOT SEE plant parasitic nematodes without the aid of a microscope (exception is the cyst of soybean cyst nematode). If you’re certain there are no legs, this is a juvenile (baby) earthworm. Earthworms feed on decaying material. They did not cause the plant damage, but are after-the-fact. No legs, “bullet” shaped, white to yellowish– These will typically be found inside the decaying seed. If the pointy end of this critter has a blackish "tooth" or dagger, it is one of many fly larvae or maggots. Seedcorn maggot is the most common species, but there are several other species that may infest decaying seeds. Maggot damage may have caused the seed/seedling problem or infested the seed after it was damaged by another critter such as wireworm. Finding brown, oblong shaped objects near hollowed out seed is most likely the pupal cases of the maggots. Finding pupal cases indicates the maggot's feeding is over. Legs, fast moving, wireworm-like, white to brownish– Catch one if you can and determine if it has obvious mouthparts. Ground beetle larvae have large mandibles that are used to capture and feed-on soft-bodied insects on or beneath the soil surface. There are several other species of immature beetles that are similar in appearance that are also beneficial in the field. Often checking underneath surface residues or soil clods when it is moist will reveal these good guys moving about. Keys to the identification of insects and other arthropods are available on-line for corn at http://www.entm.purdue.edu/entomology/ext/

Soybean Aphid Found in Soybean– (John Obermeyer)

Soybean aphid have been found on V1 soybean at the Agronomy Center for Research and Education (Tippecanoe County) on June 11. This is a week sooner than last year. This indicates that these aphids are moving from their winter host, buckthorn, onto the summer host, soybean. Mind you, this is first observation, not an alert about economic infestations. Illinois and states in the northern corn belt observed this move about one week earlier. It is too soon to speculate on what this means. Watch for more information in future issues of the Pest&Crop.

Poncho Receives EPA Registration– (John Obermeyer and Larry Bledsoe) EPA recently approved the registration of Poncho, an insecticide applied to corn seed. The active ingredient of Poncho is clothianidin and is produced by Bayer CropScience and distributed by Gustafon LLC. Clothianidin is in the neonicotinyl class of insecticides, as is imidacloprid (Gaucho and Prescribe) and thiamethoxam (Cruiser). As with the other insecticide treated seeds, Poncho will be ordered by producers pre-applied from seed companies. Our initial efficacy trials have shown better rootworm control/suppression with Poncho than with Prescribe and ProShield. It also has shown good control of black cutworm in Kentucky research trials. We are cautiously optimistic about early results of this product. Rootworm efficacy results will be presented later this year.

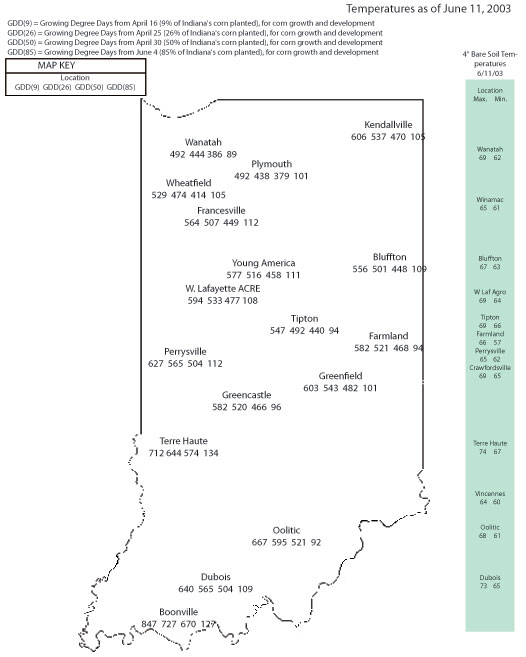

Click for Table

|

||||||||||||||||||

Blue Skies Smiling On Me...- (Bob Nielsen) The lyrics of that well-known Irving Berlin hit song have been a favorite selection on the well-worn jukebox down at the Chat 'n Chew Cafe these days as farmers yearn for a return to sunshine and warmth to rejuvenate the appearance of their corn fields. n even growth, pathetic leaf colors (yellow, silver, purple, orange, red, transparent, straw bleached), herbicide injury, nematode injury slug injury, insect injury disease injury, UAN fertilizer leaf burn, death by drowning, twisted whorls... you name the problem it is probably out there somewhere this year. In addition to these cornfield prob lems, some are wondering whether the seeminly high number of cool, cloudy days these past four weeks or so will cause lingering yield-depressing effects on the corn crop. The answer is, as you might expect, not clearcut. The effect of the cool cloudy weather itself on the corn crop to date has been a reduction in the rate of photosynthesis by the young corn plants (Nafziger, 2003). The immediaate impact of this on grain yield has been negligible at worst simply because most of the state's corn crop is only now entering the ear size determination period (post-V6). Growing conditions from here on will have a much greater effect on potential ear size. Indirectly, though, the cool cloudy (and often excesively wet) weather has impacted yield due to the increased vulnerability of the lethargic young plants to other stresses; including those listed earlier. Where significant stand loss or plant stunting has occurred from these other stresses, the yield potential has undoubtedly been reduced. The ultimate extent of the yield loss, however, is very much dependent on growing conditions the remainder of the growing season. "Blue skies smiling at me, Nothing but blue skies do I see..." (Irving Berlin, 1927). Related References: Nafziger, Emerson. 2003. Thinking About Crop Stress. Illinois Pest & Crop Bulletin (6 June). Univ. of Illinois. Available online at http://www.ag.uiuc.edu/cespubs/pest/articles/200311i.html [URL verified 6/6/03].

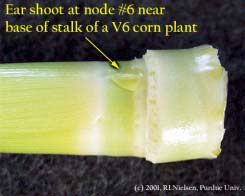

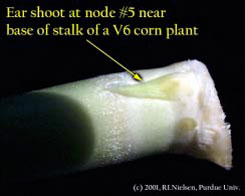

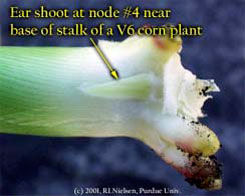

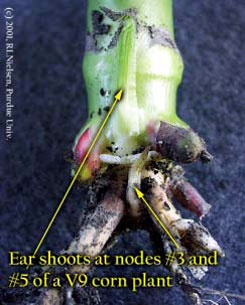

The number of harvestable kernels per ear is an important contributor to the grain yield potential of a corn plant. Severe plant stress during ear formation may limit the potential ear size, and thus grain yield potential, before pollination has even occurred. Optimum growing conditions set the stage for maximum ear size potential and exceptional grain yields at harvest time. The size of what will become the harvestable ear begins by the time a corn plant has reached knee-high and finishes 7 to 10 days prior to silk emergence. Ear Shoot Development. An axillary meristem forms at each stalk node (behind the leaf sheath) beginning at the base of the stalk and continuing toward the top (acropetally for you wordsmith fans) except for the upper six to eight nodes of the plant. Each axillary meristem initiates husk leaves at the nodes of the ear shank and eventually an ear itself at the tip of the ear shank. By about the V5 or V6 stages of development (five to six visible leaf collars), the growing point (apical meristem) of the corn plant finishes the task of initiating leaf primordia and completes its developmental responsibilities by initiating the tassel primordium of the plant. At about the same time that the tassel is initiated, the uppermost harvestable (and final) ear is also initiated (Lejeune and Bernier, 1996). This uppermost ear is normally located at the 12th to 14th stalk node, corresponding to the 12th to 14th leaf. Careful removal of the leaves from a stalk, including leaf sheaths, at about growth stage V10 (ten visible leaf collars) will usually reveal 8 to 10 identifiable ear shoots. Each ear shoot originates at a stalk node, behind its respective leaf sheath. At growth stage V10, these tiny ear shoots primarily consist of husk leaf tissue. The developing ears themselves are only a fraction of an inch in length. Initially, the ear shoots found at the lower stalk nodes are longer than the ones at the upper stalk nodes simply because the lower ones were created earlier. As time marches on, the upper one or two ear shoots assume priority over all the lower ones and ultimately become the harvestable ears. Development of the upper ears is favored over the lower ones because of hormonal “checks and balances,” plus the proximity of the upper ear to the actively photosynthesizing leaves of the upper canopy. Ear Size Determination. Row number and kernel number per row are two yield components in corn. Every pair of rows is generally equal to about 20 bushels per acre (for average populations and ear lengths). For a 16-row ear, one kernel per row is equal to about five bushels per acre (for average populations). Typically, from 750 to 1000 ovules (potential kernels) develop on each ear shoot. The number of kernel rows multiplied by the number of kernels per row determines total kernel number per ear. Actual (harvestable) kernel number per ear averages between 400 and 600. Kernel row number determination of the uppermost ear begins shortly after the ear shoot is initiated (V5 to V6) and is thought to be complete by growth stage V12. Like so many other processes in the corn plant, kernel row number determination on an ear proceeds in an acropetal fashion (from base to tip). Kernel rows first initiate as “ridges” of cells that eventually differentiate into pairs of rows. Thus, row number on ears of corn is always even unless some sort of stress disrupts the developmental process. True row number is often difficult to visualize in tiny ears dissected from plants younger than about the 12-leaf stage. Row number is determined strongly by plant genetics rather than by environment. This means that row number for any given hybrid will be quite similar from year to year, regardless of growing conditions. Some exceptions to this include potential injury from the postemergence application of certain sulfonylurea herbicides or nearly complete defoliation by hail damage prior to growth stage V12. The potential number of kernels per row is complete by about one week before silk emergence from the husk. Kernel number (ear length) is strongly affected by environmental stresses. This means that ear length will vary dramatically from year to year as growing conditions vary. Severe stress can greatly reduce potential kernel number per row. Conversely, excellent growing conditions can encourage unusually high potential kernel number. Related References:Bonnett, O.T. 1966. Inflorescences of Maize, Wheat, Rye, Barley, and Oats: Their Initiation and Development. Bulletin 721. Univ. of Illinois, College of Ag., Agricultural Expt. Sta.

|

||||||||||||||||||

Reasons to Attend Purdue Forage Day 2003- (Keith Johnson)

Purdue Forage Day, an event sponsored by the Purdue University Cooperative Extension Service and the Indiana Forage Council, will be held June 26 just north of Middlebury in Elkhart County. This year’s host is the Dennis Smeltzer family. The specific location of the Forage Day site is the west side of CR 8 where CR 8 and CR 10 intersect. Registration begins at 8:30 a.m. EST and the day’s activities should conclude by 4 p.m. EST. So why would someone want to attend Purdue Forage Day 2003? Consider the following:

Questions can be directed to Carol Summers, Extension Secretary, at 765-494-4783. A flier with complete details of the day can be found at: www.agry.purdue.edu/ext/forages.

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||