Harbinger. [hahr-bin-jer] noun

Anything that foreshadows a future event; omen; sign: Frost is a harbinger of winter.

Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition. at Dictionary.com, LLC.

http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/harbinger (accessed: Sep 2019).

Serious crop stress during the grain filling period of corn increases the risk of stalk rots and stalk lodging (breakage) prior to grain harvest. Examples of such serious stresses are nitrogen deficiency, foliar diseases (e.g., gray leaf spot, northern corn leaf blight, tar spot), defoliation by hail, excessively wet soils due to heavy rains, excessively dry soils due to drought, excessive heat, and lengthy periods of cloudy conditions. The effects of dry weather during grain filling on corn stalk health are accentuated in fields where root development and depth were restricted earlier in the season or, obviously, in fields with sandy soils and minimal water-holding capacity. Early-season root restriction can occur in response to saturated soils and/or shallow layers of compacted soil.

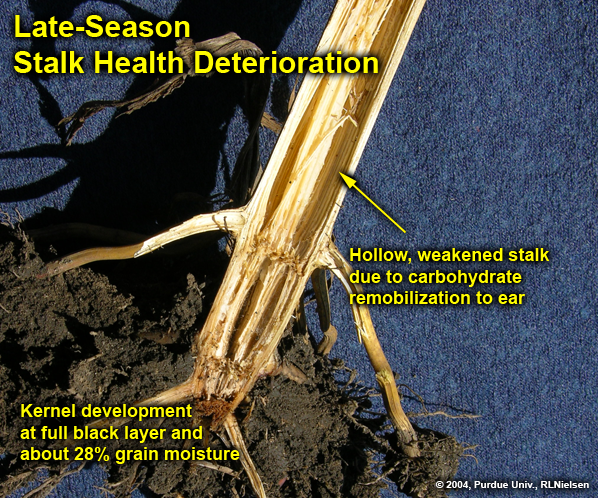

What these crop stresses share in common is that they can significantly reduce photosynthesis and, thus, the resulting carbohydrates necessary for dry matter deposition into the kernels. During grain filling, the developing kernels are a significant photosynthetic “sink” for the products of photosynthesis and respiration. Corn plants prioritize the movement of these photosynthates to the kernels, even at the expense of not maintaining the cellular health of the stalk, leaves, and roots.

When photosynthetic capacity decreases significantly during grain fill as a result of serious photosynthetic stress, plants often respond by remobilizing non-structural carbohydrates from stalk and leaf tissues to supply the intense physiological demand by the developing grain on the ears. Fields at high risk for weakened stalks and stalk rot development are those whose plants have “set” fairly decent ears (e.g., ears with a lot of kernels.) In addition to physically weakening the stalks of plants, the reduction in stalk carbohydrate concentrations and/or the consequent lower cellular maintenance of root and stalk tissues increases the susceptibility of the plant to root and stalk rot diseases.

NOTE: Even if significant stalk rot does not develop after carbohydrate remobilization from lower stalk tissue of stressed plants, the structural loss of stalk integrity itself greatly increases the risk of stalk lodging prior to grain harvest.

Severely stressed fields should be scouted in late August through early September to look for compromised stalk strength or the development of severe stalk rots. In years where crop development is delayed (like 2019), stalk quality problems may not appear until mid- to late September. Recognize that hybrids can vary greatly for late-season stalk quality even if grown in the same field due to inherent differences for late-season plant health or resistance against carbohydrate remobilization when stressed during grain fill.

Stalk breakage itself is easy to spot when walking a field. However, compromised stalks may stand unnoticed until that October storm front passes through and brings them to their proverbial knees. The simplest techniques for assessing stalk integrity involve either pushing on stalks to see whether they will collapse or bending down and pinching the lower stalk internodes to see whether they collapse easily between your fingers.

TIP: What works pretty well for me is to walk a field perpendicular to the row direction. Firmly pushing the stalks out of my way as I cross from one row to the other usually identifies weak stalks.

If possible, fields at high risk for stalk lodging or, obviously, already beginning to lodge should be harvested earlier than fields with lower risks of stalk lodging. This will minimize the risk of significant mechanical harvest losses resulting from downed corn.

Another side-effect of late-season stress during grain fill is that plants may simply “shut down” and mature prematurely, eventually evidenced by premature formation of kernel black layer (i.e., the visual indication of physiological maturity). The consequences of premature kernel black layer include not only lower grain yield, but also the likelihood of lower test weight grain.

Related Reading

Butzen, Steve and Bill Dolezal. Managing Stalk Rots in Corn – Anthracnose, Gibberella and Diplodia. Crop Insights, DuPont Pioneer. https://www.pioneer.com/us/agronomy/managing_stalk_rot.html. [URL accessed Sep 2019].

Freije, Anna, Kiersten Wise, and Bob Nielsen. 2016. Diseases of Corn: Stalk Rots. Purdue Univ. Extension Bulletin #BP-89-W. https://www.extension.purdue.edu/extmedia/BP/BP-89-W.pdf. [URL accessed Sep 2019].

Jackson, Tamra, Jennifer Rees, and Robert Harveson. Common Stalk Rot Diseases of Corn. Univ. of Nebraska Extension Pub. #EC1898. http://extensionpublications.unl.edu/assets/pdf/ec1898.pdf. [URL accessed Sep 2019].

Jardine, Doug. 2006. Stalk Rots of Corn and Sorghum. Kansas State Univ. Extension Pub. L-741. http://www.plantpath.k-state.edu/extension/publications/L741.pdf. [URL accessed Sep 2019].

Jardine, Doug and Ignacio Ciampitti. 2019. Common causes of late-season stalk lodging in corn. K-State Extension Agronomy eUpdate. https://webapp.agron.ksu.edu/agr_social/article/common-causes-of-late-season-stalk-lodging-in-corn-354-2 [URL accessed Sep 2019].

Kleczewski, Nathan. 2014. Stalk Rots on Corn. Univ. of Delaware Extension. http://extension.udel.edu/factsheets/stalk-rots-on-corn. [URL accessed Sep 2019].

MacKellar, Bruce. 2018. Tar spot is impacting corn yields and causing stalk lodging during harvest. Field Crop News, Michigan State Univ Extension. https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/tar-spot-impacting-corn-yields-and-causing-stalk-lodging-during-harvest [URL accessed Sep 2019].

Nielsen, R.L. (Bob) 2018. Effects of Stress During Grain Filling in Corn. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/GrainFillStress.html [URL accessed Sep 2019].

Nielsen, R.L. (Bob). 2019. Grain Fill Stages in Corn. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/GrainFill.html [URL accessed Sep 2019].

Nielsen, R.L. (Bob). 2018. Kernel Set Scuttlebutt. Corny News Network, Purdue Univ. http://www.kingcorn.org/news/timeless/KernelSet.html [URL accessed Sep 2019].

Sweets, Laura. 2013. Corn Stalk Rots. Integrated Pest & Crop Management, Univ. of Missouri. https://ipm.missouri.edu/IPCM/2013/8/Corn-Stalk-Rots/. [URL accessed Sep 2019].